Mental Health

Mental health: why a ‘bad trip’ with ketamine treatment isn’t what you think it is.

Editor's Note

Any medical information included is based on a personal experience. For questions or concerns regarding health, please consult a doctor or medical professional.

Please see a doctor before starting or stopping a medication.

If you have experienced emotional abuse, the following post could be potentially triggering. You can contact the Crisis Text Line by texting “START” to 741741.

It was Wednesday and time for my ketamine treatment . There is a certain amount of routine to getting my treatments. When I started with ketamine I thought I would get the IV treatments once every three months or so. That’s what everything I had read said would happen. Maybe the “treatment-resistant” part of my bipolar disorder applies to ketamine too. I don’t know. In any case, we have determined that every other week works for me. By the beginning of the second week, I start to dip in mood. I can reach suicidal thinking by the time it’s time for the next infusion. We try not to let me get to that place.

The infusions are accompanied by psychedelic “trips.” That’s just part of ketamine. In the beginning, I believed that the trip didn’t matter — the drug got in me regardless of if the trip was “good” or “bad.” A lot of my trips are “bad.” I believe this is largely because of complex post-traumatic stress disorder ( C-PTSD ). I put bad in quotes because it’s not an accurate description. The trips can be scary. I see things and feel things that are frightening or unpleasant. I have been literally terrified several times. That doesn’t mean they’re bad, though.

The trip before last Wednesday’s infusion was terrifying. I screamed so hard that I lost my voice for almost a full week. I just screamed and screamed. I was certain that I was permanently trapped in this other world that I was hallucinating. The people in the room with me, the nurses and anesthetist, looked like stick figures. They were walking around and they were talking. I didn’t know what they were saying; I was too busy screaming, “Please, somebody, notice that I’m still trapped over here in this alternate universe. Let me out!” One of them was telling me I was OK. I was insisting, “I am not OK.” As the ketamine wore off, I returned to this world and realized everything was fine. Just like every other time.

When it was time for the next infusion two weeks later, the clinic director decided to have a nurse, Colleen, sit with me for the trip. The thinking was I would feel safer and stay calmer. Maybe not scream my head off. Colleen is special to me; she has been with me since my first infusion. She has held my hand many times when trips turned frightening, always reminding me “you are safe.” It was a logical and welcome decision to have Colleen sit with me.

Except in this trip, Colleen turned evil. The world was red and black, no other colors. The walls in the room looked like the walls in “The Matrix” with green code running down black walls. Except my “code” was red. Colleen was red and terrifying. She was saying terrible things. I was convinced that the clinic was a front for an evil organization trying to do mind control and keep me trapped in that cold, black-and-red world forever. I didn’t scream because Colleen was there. I was afraid of her. I was afraid of what might happen if I screamed. What would she do to me?

Coming out of that trip, I was convinced that it would be my last. I couldn’t keep doing this, I didn’t trust anyone; that’s part of C-PTSD after all. I sent the clinic director an email the next day and asked him if he could sedate me for my next trip. Sometimes when I get especially agitated during a trip, he will add in a little sedative toward the end. When he does that, I go home with little to no memory of anything that happened during the trip. He wisely answered that the trips were important; he wanted me to experience them.

And he’s right because here’s the thing. Those “bad” trips? They aren’t bad. They’re unpleasant. They’re scary. They’re challenging and very hard to go through. But they aren’t bad. Let me explain.

The day after the Red Colleen (sorry, Colleen) trip, I went to dinner with a friend. We talked about a lot of things. This was the first time we had gotten together since my suicide attempt two months earlier. I filled her in on what it was like when I made the attempt, the ambulance ride, the emergency room, the week spent on the medical floor of the hospital, and the week after that on the psychiatric floor. I walked her through all of it. On my drive home after dinner, I had to pull into a parking lot because I was so overcome with emotion that I couldn’t keep driving. I sat in the parking lot and sobbed, letting out all the emotion that had come up while talking to my friend. It was a good, cleansing cry. When I was composed enough to drive, I made my way home. Turned out, that cry was just the beginning.

Later that same night, after everyone had gone to bed, I was up by myself. I put YouTube on the television and played my favorite music video. I had discovered this video months earlier and it had become a constant as a self-care thing I did. This video could make me cry, it could make me laugh. Something about the music touched me deep in my soul; I physically felt the music. As it played this night, tears started to flow. And I let them.

That’s something my therapist has been working on with me for over a year: Feel the feelings. Don’t avoid them, don’t push them away. Stop the struggle. Feel them. As the song came to its end, I started to smile through my tears. This is an amazing piece of music. The next video started to play. I cried some more. For the next half hour, I cried as I listened to and felt the music. But I didn’t just cry. I was turned inside out. Something broke inside me. I sobbed. I laughed. I cried about the suicide attempt. I cried about the time in the hospital. I cried about how hard the past two years have been as I rapid-cycled through bipolar , up and down, going through six different medications on the way to being declared treatment-resistant and getting off all drugs. How much work I had done with my therapist, working through all the trauma of my childhood. And I kept crying.

Then I remembered my therapist had suggested the day before that I do a meditation we know called “Working with Difficulty.” It walks you through grounding like normal. But then the guide suggests that you take any negative emotion that is coming up and place it on the worktable of your mind. Find the physical sensations of it in your body. Where are you feeling this emotion?

The guide instructs that you don’t do anything to change your breathing, just notice it, focus on it. I was sobbing hysterically. And I kept sobbing. I was breathing; it was just sobs and hyperventilating, not the calm, controlled breathing I think of when I think of meditating. I let myself do it. I gave myself permission to feel this. To express it. As I worked through this 25-minute meditation, I let myself feel all of it. And as the crying continued, that traumatized little girl who had never been allowed to cry showed up. She started to cry. This is the miracle of ketamine: It allows your mind to do things it hasn’t been able to do before. That little girl had been shamed into never crying . It wasn’t allowed. And she desperately needed to cry. She was not going to be able to heal from the trauma until she could express all that she had stuffed so far down for so long. And I was able to give her permission. I encouraged her: yes, dear one, cry. Cry until you don’t have any tears left to cry.

And she did. She cried. She rocked back and forth. She hugged a pillow and sobbed into it. I don’t have words to describe what this experience was like. The intensity was beyond description. There was one point when I felt I was back in the psychedelic part of the ketamine trip. It’s like ketamine lets your mind open in places it hasn’t opened before. This gave me the space and the permission I needed to let this little girl cry her heart out.

This was such a healing episode. I’m not the same today. I’ve been used to learning coping skills in therapy. I assumed that was the best I could hope for — learning how to cope. But, no. This was healing. The pain that that little girl had held inside all these years was released. This isn’t the first time I’ve had such a physical reaction and release of repressed pain. And it is ketamine that allowed this — caused it.

As I said in the beginning, I believe there’s no such thing as a bad trip. Every trip I’ve had that was painful ended with something good. A new insight. An expression of long-buried pain. I feel it necessary to say that I have not arrived at these good results alone. I have needed the guidance of the people at the clinic. I have needed my therapist. I have needed my psychiatrist. I don’t know psychedelics. Had I done these trips on my own, I think I would have ended up further traumatized. These trips can get very difficult and very intense. But my subconscious has been hard at work during them. Things have bubbled to the surface — the conditioned emotional responses, the fight-or-flight triggers, the repressed memories, they have been in my mind all along. Ketamine, along with therapy, has allowed those things to surface and be dealt with. It’s a very powerful and healing combination.

For more on ketamine treatments for depression, bipolar disorder, trauma and other mental illnesses, see The Mighty Community’s posts here .

If you or a loved one is affected by domestic violence or emotional abuse and need help, call The National Domestic Violence Hotline at 1-800-799-7233

We want to hear your story.

Do you want to share your story? Click here to find out how.

Photo by Just Jack on Unsplash

Early childhood trauma and lifelong struggles with mental health led me to The Mighty. I've learned the power of sharing and not staying in this madness alone. Sometimes I can support, sometimes I need support.

Ketamine trips are uncannily like near-death experiences

Photo by JR Korpa/Unsplash

by Christian Jarrett + BIO

First-hand accounts of what it is like to come close to death often contain the same recurring themes, such as the sense of leaving the body, a review of one’s life, tunnelled vision and a magical sense of reality. Mystics, optimists and people of religious faith interpret this as evidence of an afterlife. Skeptically minded neuroscientists and psychologists think that there might be a more terrestrial, neurochemical explanation – that the profound and magical near-death experience (NDE) is caused by the natural release of brain chemicals at or near the end of life.

Supporting this, observers have noted the striking similarities between first-hand accounts of NDEs and the psychedelic experiences described by people who have taken mind-altering drugs.

Perhaps, near death, the brain naturally releases the same psychoactive substances as used by drug-takers, or substances that act on the same brain receptors as the drugs. It’s also notable that psychedelic drugs have been taken by the shamans of traditional far-flung cultures through history as a way to, as they see it, visit the afterworld or speak to the dead.

To date, however, much of the evidence comparing NDEs and psychedelic trips has been anecdotal or based on questionnaire measures that arguably struggle to capture the complexity of these life-changing experiences. Pursuing this line of enquiry with a new approach, an international team of researchers led by Charlotte Martial at the University Hospital of Liège in Belgium has conducted a deep lexical analysis , comparing 625 written narrative accounts of NDEs with more than 15,000 written narrative accounts of experiences taking psychoactive drugs ( sourced from the Erowid Experience Vaults, a US-based non-profit that documents psychoactives), including 165 different substances in 10 drug classes.

The analysis, published online in Consciousness and Cognition in February 2019, uncovered remarkable similarities between the psychological effects of certain drugs – most of all ketamine, but also notably the serotonergic psychedelic drugs such as LSD – and NDEs. Indeed, the five most common category terms in the narrative accounts of people who’d taken ketamine were the same as the five most common in the accounts of NDEs, suggesting ‘shared phenomenological features associated with an altered state of perception of the self and the environment, and a departure from the everyday contents of conscious mentation’.

From category to category, the semantic similarity is profound. When referring to perceptions, both groups used the words ‘face’ and ‘vision’. The emotional word most commonly used by both was ‘fear’. In the category of consciousness and cognition, drug-takers and participants who’d been close to death most often referred to words such as ‘reality’, ‘moment’, ‘universe’, and ‘learn’. The setting was often described as ‘door’ and ‘floor’. A negative tone emphasising unpleasant bodily sensations was a shared common theme, as well.

T he findings back up the observations of some of the most famous 20th-century explorers of the psychedelic world – the American psychologist Timothy Leary described trips as ‘experiments in voluntary death’, and the British-born writer and philosopher Gerald Heard said of the psychedelic experience: ‘That’s what death is going to be like. And, oh, what fun it will be!’ But claims about the similarities go beyond these famous reports. The new research legitimises the long-standing analogy between the experience of dying and the acute effects of certain psychoactive drugs. Links between dying, death, a potential existence of afterlife and certain hallucinogenic plants and fungi emerged independently across different societies, and are also ubiquitous in contemporary psychedelic culture. However, empirical research has been scarce, until now.

To an extent, the results also support neurochemical accounts of NDEs, and especially the controversial proposal that such experiences are caused by the natural release of an as-yet-to-be-discovered ketamine-like drug in the brain (adding plausibility to this account, ketamine is known to act on neural receptors that, when activated, help to prevent cell death and offer protection from lack of oxygen).

‘This body of empirical evidence supports that near-death is by itself an altered state of consciousness that can be investigated using quantitative psychometric scales,’ the researchers say. That in itself is quite a realisation. As they note wryly, ‘Unlike other human experiences, dying is difficult to study under controlled laboratory conditions by means of repeated measurements,’ making it a challenge to investigate NDEs experimentally. Although the new research lacks laboratory control, on the plus side, the lexical comparison that Martial’s team conducted is ‘massive both in terms of the investigated drugs and the number of associated reports’.

The limitations of the current approach, including a reliance on retrospective reports, often decades-old, means, as the researchers put it, that they cannot validate nor refute the neurochemical models of NDEs. ‘However,’ they add, ‘our results do provide evidence that ketamine, as well as other psychoactive substances, result in a state phenomenologically similar to that of “dying” (understood as the content of NDE narratives). This could have important implications for the pharmacological induction of NDE-like states for scientific purposes, as well as for therapeutic uses in the terminally ill as means to alleviate death anxiety. We believe that the development of evidence-based treatments for such anxiety is a cornerstone of a more compassionate approach towards the universal experience of transitioning between life and death.’

They also warn experimenters to be prepared and beware. ‘The intensity of the experience elicited by [ketamine] relative to cannabis may represent a shock to unsuspecting users, who could retrospectively report the belief of being close to death,’ the researchers say. Pot-smokers, you’ve been warned. As one of the most intense and life-changing altered states known, an NDE is no toke on a pipe after class or work.

This is an adaptation of an article originally published by The British Psychological Society’s Research Digest.

Gentle medicine could radically transform medical practice

Jacob Stegenga

Childhood and adolescence

For a child, being carefree is intrinsic to a well-lived life

Luara Ferracioli

Meaning and the good life

Sooner or later we all face death. Will a sense of meaning help us?

Warren Ward

Philosophy of mind

Think of mental disorders as the mind’s ‘sticky tendencies’

Kristopher Nielsen

Philosophy cannot resolve the question ‘How should we live?’

David Ellis

Love and friendship

Your love story is a narrative that gets written in tandem

Pilar Lopez-Cantero

July 3, 2024

Is a Drug Even Needed to Induce a Psychedelic Experience?

A Stanford anesthesiologist deconstructs the component parts of what it means to undergo a psychedelic trip

By Gary Stix

Jorm Sangsorn/Getty Images

A debate has long percolated among researchers as to whether what happens after taking a psychedelic drug results from the placebo effect—rooted in a person’s belief that taking psilocybin or ketamine is going to give them a transformative experience. Boris D. Heifets, an associate professor of anesthesiology at the Stanford University School of Medicine, has been tackling this question amid his broader laboratory investigations of what exactly happens in mind and brain when someone takes a psychedelic . How much of this sometimes life-altering experience is chemical and empirical, and how much is mental and subjective? It turns out the effects may consist of a lot more than just a simple biochemical response to a drug activating, say, the brain’s serotonin receptors. Heifets recently talked with Scientific American about his years-long quest to define the essence of the psychedelic experience.

[ An edited transcript of the interview follows .]

Are we coming any closer to understanding how psychedelics work and how they work in the context of therapy. Are we closer to using these transformational experiences to treat psychiatric disorders?

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing . By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Having been in this field for a while, there’s still this inescapable problem of how to study psychedelics. One framework that I find very useful is thinking about it in three categories.

There's the biochemical drug effect, which interacts with basic brain biology—chemicals interacting with receptors on cells. That happens whether or not you can “feel” the effect of the drug. Then there is the conscious experience related to changes in sensation and revelatory, hallucinatory and ecstatic feelings. These experiences are closely tied to taking the drug, and usually we think of them as caused by the drug. But it is actually quite difficult to say whether a lasting change in mood or outlook was a result of the drug—a biochemical effect—or the trip itself, the experiential effect.

The third factor, then, is all of those aspects of the overall drug experience that are independent of the drug or trip—the non-drug factors, what [psychologist and psychedelics advocate] Timothy Leary called the “set and setting.” How much does your state of mind and the setting in which you take a drug influence the outcome? This category includes expectations about improvement in, say, your depression, expectations about the experience, the stress level in the environment. It would also include integration, making sense of these intense experiences afterward and integrating them into your life. And it’s useful to put each of these things in its own box because I think each of them is somewhat isolated. The goal is to make each box smaller and smaller, to really deconstruct the pieces.

So how have you gone about examining all this?

One example of how we’ve used this framework in our research is an experiment in which we gave [participants with depression] ketamine during general anesthesia . The idea was to explore just the biochemical drug effect by blanking out conscious experience to see whether people got better from their depression.

Our intention with this experiment was to get at this question that a lot of people have been asking: Is it the drug or the trip that is making someone better? You can address that question in a couple of different ways. One is to redesign the drug to eliminate the trip. But that is a very long process. As an anesthesiologist, my solution of course was to address the problem with the use of general anesthesia. We used the anesthetics to basically suppress conscious experience of the associated psychological effects of ketamine, which many people think may be relevant and even crucial to the antidepressant effects.

We collaborated closely with psychiatrists Laura Hack and Alan Schatzberg, [both] at Stanford, and we designed this study to look like every ketamine study in the past 15 years. We picked the same type of participants: [people] with moderate to severe major depressive disorder who had failed other treatments for moderate or severe depression. We administered the same questionnaires; we gave the same dose of ketamine.

The difference was these participants happened to be coming in for surgery for hips, knees, hernias, and while they were under general anesthesia, we gave them a standard antidepressant dose of ketamine. Because the patients were under anesthesia and couldn’t tell whether they were on a drug or not, this may have been the first blinded study of ketamine.

What was surprising was that the placebo group [who received no ketamine] also got better, indistinguishably from those who received the drug. Almost 60 percent of the patients had their symptom load cut in half, and there was at least 30 percent remission from major depressive disorder. These were patients who had been sick for years, and that finding was a big surprise. In a sense, it was a failed trial in that we couldn't tell the difference between our two groups.

What I take from that is really that this doesn't say much about how ketamine works. What it does say is just how big a therapeutic effect you can attribute to nondrug factors. That’s what people call the placebo effect.

It’s a word that describes everything from sugar pills to our surgeries. In our case, it may have had something to do with the preparation for the surgery. We messaged patients early; we engaged with them early. They weren’t used to people being interested in their mental health.

What did you discuss?

We talked to them for hours; we heard about their histories; we got to know them. I think they felt seen and heard in a way that many patients don’t, going into surgery. I’m thinking about parallels with the preparation steps for psychedelic trials. Patients in both types of research are motivated to be in these studies. In our study, they were told that they were testing the therapeutic potential of a drug and that there was a 50–50 chance they might get it. And then there was the big event of actually having the surgery. In this case, it was similar to having a psychedelic trial—a big, stressful, life-impacting event.

The patients closed their eyes and opened them after the surgery, and in many cases, they had the sense that no time had passed. They knew they went through something because they had the bandages and scars to prove it. What I take from that is that these nondrug effects, such as expectations of a particular outcome, are almost certainly present in most psychedelic trials and are independently able to drive a big therapeutic effect.

It became obvious that people had powerful experiences. Most people don't spontaneously improve from years of depression. After surgery, they get worse. That's what the data show. And the fact that we're able to make this degree of a positive impact after hours and hours of interpersonal contact and messaging, that’s important. This was a really clear demonstration to me that nondrug factors, such as expectations and feelings of hope, contribute a substantial portion to the effects we’ve seen. And you would be foolish to disregard those components in designing a therapy. And, you know, the truth is that most clinicians make use of these techniques every day in building a rapport with patients, leveraging this placebo response.

Does that suggest in any way that the effects of psychedelics might be substantially—or perhaps entirely—placebo effects?

So this is where I think you have to ask the question: What do we mean by placebo? Characteristically, people use the word placebo in a kind of a dismissive way, right? If a person responds to placebo, the subtle implication is there was nothing wrong. And that’s not what we’re talking about here.

Think about everyday situations that bring about life changes. A heart attack or near-death experience may cause someone in a high stress job to change their job and lifestyle habits—exercising and eating better. That all can be grouped under the label of a placebo effect.

Another possibility to achieve the same goal is having a transformational experience that you then use to make changes in your life. So the question is: How do you do this in a practical way? You can’t exactly go out and give people heart attacks or even send them on life-changing experiences, such as skydiving or on trips to the Riviera. But you can give them a psychedelic. That’s a big, powerful experience. In many cases, that is unique in some people’s lives and confers the opportunity to make changes for the better.

How does giving an actual psychedelic drug to someone in a clinical trial relate to the three categories you mentioned earlier?

Let’s circle back to this idea that psychedelic transformation could rely either on the biochemical effect, the experience of the trip itself, or nondrug factors. Our study of ketamine during anesthesia really highlighted the role of nondrug factors such as expectation but didn’t really get at the question of “Is it the drug or the trip?”

To answer that, some [of my] scientist colleagues are testing nonpsychedelics, or nonhallucinogenic psychedelic derivatives, to see whether patients with depression, for example, get better after treatment with a drug that can cause some of the same biochemical changes as a classical psychedelic but doesn’t have a “trip” associated with it. That’s “taking the trip out of the drug.” But what if you could “take the drug out of the trip,” meaning [the creation of] an experience that is reproducible across people that checks many of the same boxes as a classic psychedelic-induced trip but that doesn’t actually require the use of a psychedelic molecule? So what, in this context, you provide people with is a profound experience that can even be somewhat standardized so you can study it. And it would be powerful and vivid and meaningful and revelatory. Do you get the same types of effects?

That would not be definitive evidence. But it would strongly suggest that maybe there’s nothing intrinsically special about the activity of a drug that activates a particular receptor that mediates the effects of psychedelics. What that would do is put front and center the role of human experience in psychological transformation.

So you might be able to bypass the need for a psychedelic drug if you can get the same result with a nonpsychoactive drug?

Maybe you can—we just don’t know. That’s an empirical question.

To try to answer that question, I’ve worked closely with Harrison Chow, also an anesthesiologist at Stanford, on a protocol that we call “dreaming during anesthesia.” It's really a state of consciousness that happens before emergence from anesthesia. When patients awaken from surgery, they progress from a state that is deeper than sleep. And they pass through a number of conscious states, some of which produce dreams . They wake up, and about 20 percent of patients will have some dream memory imagery.

What we do is prolong that process and use EEG [electroencephalography] to home in on a specific biomarker of that state. We can hold someone in this preemergent state for 15 minutes. Participants wake up, and the stories they tell are very hard to ignore. These are some of the most vivid dreams they’ve ever had. They say things like “that was more real than real.” The participants with trauma dream of reintegrating their body map, reimagining their body [as] once again whole. We had a participant who had been assigned male at birth and had gender-affirming] surgery. She had been in the military and reimagined her life before her gender-affirming care. She saw herself doing high-intensity military training exercises, now with her body aligning with her gender.

These are intense experiences—vivid, emotionally salient, possibly hallucinatory. We published a couple of case reports now where we actually have seen therapeutic effects on a par with what we see in psychedelic medicine: powerful experiences followed by a resolution of symptoms in a psychiatric disorder.

What we’re seeing is a shared physiology in terms of EEG results for these dream states and the EEGs present for psychedelics. We see at least some shared phenomenology in terms of description of the experiences, and there are also similar therapeutic effects.

What are some of your next steps?

In addition to possibly producing a very compelling therapeutic using the common anesthetic propofol, we are working hard to develop experimental tools using anesthesia, using our knowledge of how placebo works in the brain to separate these three factors: the drug effect, the experiential effect and nondrug factors. At least two of those big effects, neither of which depends on administering a psychedelic, appear to be capable of generating a profound therapeutic impact that certainly would be sufficient on its own to claim the outcomes seen in psychedelic trials. And that, to me, shows that maybe the emphasis is misplaced when we're focused on reengineering the drug to get rid of hallucinogenic effects. We should be focused on reengineering the experience.

But we're still working on number three, the drug effect. We have collaborations with David Olson, a chemist at the University of California, Davis, who has pioneered the use of nonhallucinogenic psychedelics. We are helping to characterize the profound neuroplastic effects of a drug he has developed that appears, at least in mice, not to trigger the same type of brain activation that classical psychedelics do. What I’m trying to convey is that, using these approaches, we are able to get some traction to experimentally define, isolate and identify the components of this very complex therapeutic package we call psychedelic therapy.

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

- Your Health

- Treatments & Tests

- Health Inc.

- Public Health

The ketamine economy: New mental health clinics are a 'Wild West' with few rules

Patients report that ketamine infusions can be lifesaving, with immediate improvement for severe depression. But dosage and safety measures vary widely at the hundreds of clinics that have opened. Yana Iskayeva/Getty Images hide caption

Patients report that ketamine infusions can be lifesaving, with immediate improvement for severe depression. But dosage and safety measures vary widely at the hundreds of clinics that have opened.

In late 2022, Sarah Gutilla's treatment-resistant depression had grown so severe that she was actively contemplating suicide. Raised in foster care, the 34-year-old's childhood was marked by physical violence, sexual abuse and drug use, leaving her with life-threatening mental scars.

Out of desperation, her husband scraped together $600 for the first of six rounds of intravenous ketamine therapy at Ketamine Clinics Los Angeles, which administers the generic anesthetic for off-label uses such as treating depression. When Gutilla got into an Uber for the 75-mile ride to Los Angeles, it was the first time she had left her home in Llano, Calif., in two years. The results, she says, were instant.

"The amount of relief I felt after the first treatment was what I think 'normal' is supposed to feel like," she says. "I've never felt so OK and so at peace."

For-profit ketamine clinics have proliferated over the past few years, offering infusions for a wide array of mental health issues, including obsessive-compulsive disorder, depression and anxiety. Although the off-label use of ketamine hydrochloride, a Schedule III drug approved by the Food and Drug Administration as an anesthetic in 1970, was considered radical just a decade ago, now between 500 and 750 ketamine clinics have cropped up across the United States.

Market analysis firm Grand View Research pegged industry revenues at $3.1 billion in 2022, and it projects them to more than double to $6.9 billion by 2030. Most insurance doesn't cover ketamine for mental health, so patients must pay out-of-pocket.

Off-label use

While it's legal for doctors to prescribe ketamine, the FDA hasn't approved it for mental health treatment, which means that individual practitioners develop their own treatment protocols. The result is wide variability among providers, with some favoring gradual, low-dosage treatments while others advocate larger amounts that can induce hallucinations, as the drug is a psychedelic at the right doses.

"Ketamine is the Wild West," says Dustin Robinson, the managing principal of Iter Investments, a venture capital firm specializing in hallucinogenic drug treatments.

Ketamine practitioners stress that the drug's emergence as a mental health treatment is driven by a desperate need. Depression is the leading cause of disability in the U.S. for individuals ages 15 to 44, according to the National Institute of Mental Health, and around 25% of adults experience a diagnosable mental disorder in any given year.

Shots - Health News

From chaos to calm: a life changed by ketamine.

Meanwhile, many insurance plans cover mental health services at lower rates than physical health care, despite laws requiring parity . Thus, many patients with mental health disorders receive little or no care early on and are desperate by the time they visit a ketamine clinic, says Dr. Steven Siegel , chair of psychiatry and the behavioral sciences at the University of Southern California's Keck School of Medicine.

Matthew Perry and Elon Musk

But the revelation that Friends star Matthew Perry died in part from a large dose of ketamine , as well as billionaire Elon Musk's open use of the drug , has piqued fresh scrutiny of ketamine and its regulatory environment, or lack thereof.

Commercial ketamine clinics often offer same-day appointments in which patients can pay out-of-pocket for a drug that renders immediate results. The ketamine is administered intravenously, and patients are often given blankets, headphones and an eye mask to heighten the dissociative feeling of not being in one's body. A typical dose of ketamine to treat depression, which is one-tenth the dosage used in anesthesia, costs clinics about $1, but clinics charge $600 to $1,000 per treatment.

Ketamine is still shadowed by its reputation as the party drug known as "Special K"; Siegel's first grant from the National Institutes of Health was to study ketamine as a drug of abuse. It has the potential to send users down a "K-hole," otherwise known as a bad trip, and can induce psychosis. Research in animals and recreational users has shown that chronic use of the drug impairs both short- and long-term cognition.

Perry's drowning death in October raised alarms when the initial toxicology screening attributed his death to the acute effects of ketamine. A December report revealed Perry received infusion therapy a week before his death but that the fatal blow was a high dose of the substance taken with an opioid and a sedative on the day of his death — indicating that medical ketamine was not to blame.

A variety of protocols

Sam Mandel co-founded Ketamine Clinics Los Angeles in 2014 with his father, Steven Mandel, an anesthesiologist with a background in clinical psychology, and Sam Mandel says the clinic has established its own protocol. That includes monitoring a patient's vital signs during treatment and keeping psychiatrists and other mental health practitioners on standby to ensure safety. Initial treatment starts with a low dose and increases if that is not effective.

While many clinics follow the Mandels' graduated approach, the dosing protocol at MY Self Wellness, a ketamine clinic in Bonita Springs, Fla., is geared toward triggering a psychedelic episode.

Christina Thomas, president of MY Self Wellness, says she developed her clinic's procedures against a list of "what not to do" based on the bad experiences that people have reported at other clinics.

A sign for a ketamine clinic that has four locations in South Florida. Between 500 and 750 similar clinics exist across the U.S., according to market research firm Grand View Research. Ricardo Ramirez Buxeda/Orlando Sentinel/Tribune News Service via Getty Images hide caption

A sign for a ketamine clinic that has four locations in South Florida. Between 500 and 750 similar clinics exist across the U.S., according to market research firm Grand View Research.

The field isn't entirely unregulated: State medical and nursing boards oversee physicians and nurses, while the FDA and Drug Enforcement Administration regulate ketamine. But most anesthesiologists don't have a background in mental health, while psychiatrists don't know much about anesthesia, Sam Mandel notes. He said a collaborative, multidisciplinary approach is needed to develop standards across the field, particularly because ketamine can affect vital signs such as blood pressure and respiration.

The protocols governing Spravato, an FDA-approved medication based on a close chemical cousin of ketamine called esketamine, are illustrative. Because it has the potential for serious side effects, it falls under the FDA's Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS) program, which puts extra requirements in place, says Iter Investments' Robinson. Spravato's REMS requires two hours of monitoring after each dose and prohibits patients from driving on treatment days.

Nasal Spray Is A New Antidepressant Option For People At High Risk of Suicide

Generic ketamine, by contrast, has no REMS requirements. And because it is generic, cheap and already on the market, drugmakers have little financial incentive to undertake the costly clinical trials that would be required for FDA approval for specific psychiatric conditions.

That leaves it to the patient to assess ketamine providers. Clinics dedicated to intravenous infusions, rather than offering the treatment as an add-on, may be more familiar with the nuances of administering the drug. Ideally, practitioners should have mental health and anesthesia expertise or have multiple specialties under one roof, and clinics should be equipped with hospital-grade monitoring equipment, Mandel says.

The University of Southern California's Siegel, who has researched ketamine since 2003, said the drug is especially useful as an emergency intervention, abating suicidal thoughts for long enough to give traditional treatments, like talk therapy and SSRI antidepressants, time to take effect.

"The solutions that we have and have had up until now have failed us," Mandel says.

The drug is now popular enough as a mental health treatment that the name of Mandel's clinic is a daily sight for thousands of Angelenos, as it appears on 26 Adopt A Highway signs along the 405 and 10 freeways.

And the psychedelic renaissance in mental health is accelerating. A drug containing MDMA, known as ecstasy or molly, is expected to receive FDA approval in 2024. A drug with psilocybin, the active ingredient in "magic mushrooms," could launch as early as 2027, the same year a stroke medicine with the active ingredient DMT, a hallucinogen, is expected to debut.

Psychedelic drugs may launch a new era in psychiatric treatment, brain scientists say

Iter Investments' Robinson says many ketamine clinics have opened in anticipation of the expanded psychedelic market. Since these new drugs will likely be covered by insurance, Robinson advises clinics to offer FDA-approved treatments such as Spravato so they'll have the proper insurance infrastructure and staff in place.

For now, Sarah Gutilla will pay out-of-pocket for ketamine treatments. One year after her first round of infusions, she and her husband are saving for her second. In the meantime, she spends her days on her ranch in Llano, where she rescues dogs and horses and relies on telehealth therapy and psychiatric medications.

While the infusions aren't "a magic fix," they are a tool to help her move in the right direction.

"There used to be no light at the end of the tunnel," she says. "Ketamine literally saved my life."

This article was produced by KFF Health News , a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. KFF Health News is the publisher of California Healthline , an editorially independent service of the California Health Care Foundation .

- mental health

- Obsessive Compulsive Disorder

- psychedelic drugs

What Is Ketamine and Is It Effective for Depression?

Find out what ketamine is, how ketamine therapy is used to treat depression, what side effects it can have and more.

This article is based on reporting that features expert sources.

What Is Ketamine?

After the death of actor Matthew Perry, ketamine, a longtime party drug, came into the public eye for a new reason. Perry had been undergoing ketamine infusion therapy for depression, which has been determined as a contributing factor in his death. Ketamine, initially recognized for its potent anesthetic and dissociative properties, has emerged as a treatment for depression .

Getty Images

Perry's death has raised questions about the increasing reliance on ketamine by doctors who see it as a promising alternative therapy for depression and other mental health disorders , although its long-term benefits and effects have not been well researched.

To the everyday person, a depression diagnosis might seem straightforward: symptoms of a persistent sad mood , lack of energy and little enjoyment in pleasurable activities, all to be remedied by psychotherapy and a medication. However, it's not so simple.

Dr. Ryan Sultan, a teaching psychiatrist, research scientist and the director of mental health informatics at Columbia University Irving Medical Center/New York State Psychiatric Institute in New York, explains that depression is a complex condition with various subtypes, impacted by genetics and other underlying factors.

Given the complexity of the diagnosis, any additional tool – such as ketamine – in the therapeutic arsenal is helpful. It might end up as the most successful treatment for an individual, finally alleviating their depressive symptoms.

Ketamine is a powerful medication that has been safely used in medical and veterinary science for over a century, mainly as an anesthetic. Ketamine can induce a state of sedation (feeling calm and relaxed), immobility, relief from pain, hallucinations and amnesia. It has gained recent popularity for treating depression. Ketamine is short for ketamine hydrochloride, which the Drug Enforcement Administration considers a Schedule III controlled substance, meaning it has the potential for abuse and dependence.

There are various formulations of ketamine. Ketamine is a mixture of two molecules called R-ketamine and S-ketamine, sometimes referred to as arketamine and esketamine, respectively. All formulations of ketamine, except Food and Drug Administration-approved Spravato, are being used off-label when used for the treatment of depression.

The Food and Drug Administration circulated a press release on October 10, 2023, stating, "Ketamine is not FDA approved for the treatment of any psychiatric disorder. FDA is aware that compounded ketamine products have been marketed for a wide variety of psychiatric disorders (e.g., depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and obsessive-compulsive disorder); however, FDA has not determined that ketamine is safe and effective for such uses."

Currently, ketamine is considered on-label only for anesthesia.

The FDA has not approved ketamine for depression, except for the nasal spray form of ketamine called Spravato, which it approved in 2019. There are currently no confirmed plans to approve other forms of ketamine for the treatment of depression, but as more research continues, this may change. Spravato is "approved as a nasal spray for treatment-resistant depression in adults and for depressive symptoms in adults with major depressive disorder with acute suicidal ideation or behavior (in conjunction with an oral antidepressant)," according to the FDA's press release.

What Types of Depression Is Ketamine Therapy Used for?

Ketamine is primarily used for a type of depression called treatment-resistant depression . TRD is a type of major depressive disorder that doesn't respond to traditional first-line treatment, like selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, such as Prozac or Zoloft.

Ketamine therapy can be effective for some patients, says Dr. Helen Lavretsky, professor of psychiatry in-residence at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA. She's also director of the Late-Life Mood, Stress and Wellness Research Program and director of the Integrative Psychiatry Clinic.

"Ketamine use should be reserved for truly treatment-resistant patients who failed to respond to two or more antidepressants administered in the optimal dose for at least two to four months," she says.

How Does Ketamine Therapy Help With Depression Symptoms?

Dr. Martha Koo, the founder and chief medical officer at Neuro Wellness Spa and a board-certified provider in psychiatry and addiction medicine based in Manhattan Beach, California, says that the reputation of ketamine being a party drug and a horse tranquilizer may cause some skepticism.

Ketamine is in a drug class called dissociative anesthetics, and ketamine is specifically an N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonist. Koo explains that this means that ketamine acts on the glutamatergic system in the brain, which is responsible for:

- Growing new pathways and connections between brain cells, called neuronal growth

- Maintaining neuroplasticity, which is the ability to learn new skills and become better at them

- Helping different parts of the brain work together as a team, called neuronal interconnectivity

- Helping you feel energized and focused, while also maintaining a sense of calm

With ketamine giving a boost to the glutamatergic system, it may help people struggling with depression to feel like their brain is working more harmoniously, giving them energy, strength and focus to be able to face the day.

Is Ketamine Effective for Depression?

Ketamine administered intravenously – which can involve up to six infusions – has shown positive effects in patients within a few hours, relieving depressive symptoms and suicidal thoughts, says Lavretsky. Intravenously administered ketamine can quickly resolve "depressive symptoms and suicidal ideations" in patients under 65 years old, she says. "However, the need for IV access and physician monitoring limits its uses. In addition, the medication's long-term use efficacy and safety are not well known."

In addition, "it's important to acknowledge that as ketamine treatments have been administered to broader populations, there has been variability in its effectiveness," notes Sultan.

Research suggests that ketamine administered through the nose (Spravato) or taken orally requires two to four weeks of treatment before taking effect.

The effects of ketamine depend on the individual, the type of ketamine they received and the dosage. The body will eliminate ketamine in a matter of hours, but the effects of it may last for more time, up to a week or longer.

Ketamine dosage and frequency

There are a few routes and types of medications for ketamine for depression. In the October 2023 press release, the FDA reiterates, "Compounded drugs, including compounded ketamine products, are not FDA approved, which means FDA has not evaluated their safety, effectiveness or quality prior to marketing. Therefore, compounded drugs do not have any FDA-approved indications or routes of administration."

This means there are no FDA-regulated routes or dosages for ketamine, except in the case of FDA-approved Spravato. But, here are some of the typical routes of administration and dosages that health care providers may use:

- Intravenous ketamine. Koo says that IV ketamine works the fastest, with symptom relief within a few hours. IV ketamine doses are weight-dependent and commonly administered at 0.5 mg/kg. Dr. Danielle Greenman, a functional medicine physician and head of ketamine-assisted psychotherapy at Blum Center for Health in New York, says IV ketamine peaks around one minute, and many providers prefer IV ketamine due to its rapid onset, ability for more precise dosing and fewer side effects.

- Intramuscular ketamine. Ketamine can also be given as a shot into the muscle, usually in the upper outer gluteus. A standard IM dose is 0.25 to 0.5 mg/kg of body weight. Greenman says IM ketamine peaks around five minutes.

- Oral ketamine. A standard dose is 1 mg/kg of body weight. Greenman says oral ketamine effects peak at about 15 to 30 minutes.

- Ketamine lozenges. Greenman says this is a less invasive option for patients to do the treatment at home, but less medication will be able to enter the bloodstream. Standard dosing varies.

- Intranasal ketamine (Spravato). As this is the only FDA-approved formulation of ketamine for depression, there is standard dosing. The dose for TRD is 56 mg for adults, which may increase to 84 mg. For major depressive disorder or suicidal ideation, the dose is 84 mg for adults. For nasal administration, medical providers give patients a nasal spray device, similar to one you might use for a stuffy nose. Greenman says peak effect of intranasal ketamine is around 15 minutes.

Spravato is usually recommended for at least six months. But if considered effective, your provider may recommend you take the medication long term. Since the other forms of ketamine are off-label, there aren't regulated treatment durations. Your doctor may recommend you have more ketamine treatments in the beginning, and then have the treatment less often as a maintenance therapy. Treatment duration and frequency depend on the discussion between a patient and their medical provider.

Ketamine Benefits

Using ketamine for depression has a few key benefits:

- Rapid onset. Koo says that other medications would take four to six weeks to achieve remission, whereas ketamine is going to be much faster.

- Relief from depression symptoms. Especially with TRD, other treatments may not be working. Ketamine may be the treatment to finally provide relief from depression.

- May be combined with psychotherapy. Because ketamine can induce an altered state of consciousness, individuals may be more receptive to emotional processing and therapy.

Ketamine Side Effects and Risks

Using ketamine for depression also has side effects and risks:

- Medical surveillance is needed after treatment. All patients require some level of medical surveillance after treatment, like staying in the clinic so the staff can watch vital signs and assess for loss of consciousness. Koo also says that patients cannot drive post-session for at least 24 hours.

- Dissociative effects. The effects differ between individuals, but some may experience emotional numbness or detachment, out-of-body experiences or hallucinations. Koo adds that these effects can be uncomfortable ketamine side effects for many people.

- Nausea. Nausea is one of the most common side effects, and usually, the side effect is mitigated with medications prior to treatment.

- Headaches. Headaches are another common effect, also treated with medicine beforehand.

- Abuse potential . Proper screening and ongoing monitoring are essential with ketamine administration. It’s vital that people work with licensed psychiatric clinicians who can prescribe appropriately and watch for signs of misuse or dependence.

Is ketamine addictive?

Dr. Leonardo Vando, the Maryland-based medical director of Mindbloom, a platform that provides services to affiliated psychiatric medical practices in more than 35 states, says that ketamine is "not physically addictive in the way that substances like alcohol and nicotine are. However, it is possible to become psychologically dependent on ketamine – especially when it is taken without proper clinical supervision."

Are there ketamine withdrawal symptoms after treatments end?

When ketamine for depression is taken under medical supervision, withdrawal symptoms are less common. The dosage of ketamine administered is not meant to induce physiological dependence.

When ketamine is abused, American Addition Centers cites common symptoms may include:

- Drug cravings

- Mood swings

- Heart palpitations

Who Is Eligible for Ketamine Therapy?

Ketamine therapy is usually for individuals with depression who have not responded to other types of treatment or those with active suicidal thoughts.

Beyond that, anyone considering ketamine therapy would need additional medical clearance. This process includes:

- Patient intake. Your provider will take a complete medical history, family history , surgical history, medication list and allergies.

- Rule out contraindications. Your provider will need to make sure you don't have a condition that makes taking ketamine unsafe, like pregnancy, heart disease , uncontrolled high blood pressure, untreated thyroid disease, schizophrenia, acute drug intoxication or acute mania.

- Psychological assessment. Greenman says she checks for risk of abuse or active substance use disorders or other mental health conditions that could interact with ketamine, like psychosis.

- Assessment of developmental and trauma history. Greenman wants to understand what her patients have tried for previous treatment, their religious or spiritual preferences and their support system at home.

- Informed consent. Everyone needs to sign consent forms and agree that they understand the risks and benefits of ketamine therapy and the importance of regular medical follow-ups.

Does Insurance Cover Ketamine?

Sultan says that because ketamine is often used off-label, it's difficult to get any insurance coverage. He adds that some ketamine providers offer financial assistance programs to help patients pay for treatments.

"Advocacy groups and health care professionals are actively engaged in efforts to promote greater access to and affordability of ketamine treatment," he explains.

With continued research on safety and efficacy, insurance coverage may improve.

Understanding Male Depression

The U.S. News Health team delivers accurate information about health, nutrition and fitness, as well as in-depth medical condition guides. All of our stories rely on multiple, independent sources and experts in the field, such as medical doctors and licensed nutritionists. To learn more about how we keep our content accurate and trustworthy, read our editorial guidelines .

Greenman is a functional medicine physician and head of ketamine-assisted psychotherapy at Blum Center for Health in New York.

Koo is the founder and chief medical officer at Neuro Wellness Spa. She is board-certified in psychiatry and addiction medicine. She is also a medical director and clinical supervisor at Clear Recovery Center and is on the board of directors of the Clinical TMS Society. She is based in Manhattan Beach, California.

Sultan is a teaching psychiatrist, research scientist and the director of Mental Health Informatics at Columbia University Irving Medical Center/New York State Psychiatric Institute in New York.

Vando is based in Maryland and is the medical director of Mindbloom, a platform that provides services to affiliated psychiatric medical practices in more than 35 states.

Lavretsky is a professor of psychiatry in-residence at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA. She’s also director of the Late-Life Mood, Stress and Wellness Research Program and director of the Integrative Psychiatry Clinic.

Tags: mental health , depression , drugs , psychology , psychiatry

Most Popular

Patient Advice

Best Hospitals

health disclaimer »

Disclaimer and a note about your health ».

Your Health

A guide to nutrition and wellness from the health team at U.S. News & World Report.

You May Also Like

Get a second opinion.

Paul Wynn Aug. 22, 2024

How Chemotherapy Works

Payton Sy Aug. 20, 2024

What Is Bariatric Surgery?

Claire Wolters and Christine Comizio Aug. 19, 2024

Medicare Coverage: Alternative Medicine

Christine Comizio Aug. 16, 2024

Barbara Sadick Aug. 14, 2024

Reduce Health Care Costs in Retirement

Elaine K. Howley Aug. 12, 2024

Using Medicare’s Telehealth Coverage

Elaine K. Howley Aug. 9, 2024

9 Screenings to Lower Medicare Costs

Elaine K. Howley Aug. 7, 2024

How SHIPs Can Help

Payton Sy Aug. 7, 2024

Preparing for Surgery

Ruben Castaneda and Christine Comizio Aug. 7, 2024

Should You Try Ketamine Therapy?

6 questions to ask yourself before trying ketamine therapy..

Posted August 16, 2021 | Reviewed by Devon Frye

- What Is Ketamine?

- Take our Depression Test

- Find a therapist to overcome depression

- Ketamine is a dissociative anesthetic that is thought to improve the brain's neuroplasticity and was legalized for therapeutic benefits.

- Ketamine has also been found effective in combating treatment-resistant depression, PTSD, and anxiety.

- Ketamine is not 100 percent effective and is usually rather expensive (at least several hundred dollars a "session").

- Ketamine therapy is as much (if not more) about the “therapy” than it is about the “ketamine.”

If you clicked on this headline, there’s a good chance the answer to your question is: possibly! Ketamine is safe and effective. If a passive-aggressive colleague sent you this link, maybe the cure for your problems is to move desks. If you googled this question, make sure the article you're reading isn't posted by a ketamine therapy clinic because, and you'll never believe this: they have an incentive for you to try ketamine therapy .

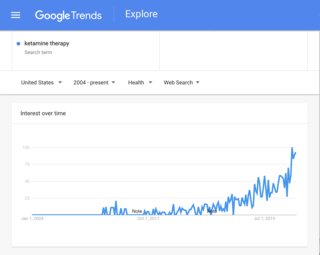

There has been a marked increase in exposure and interest for this novel therapy, as you can see in the Google Trends chart here. Ketamine has been in a state of heightened media frenzy ever since the FDA approved the ketamine-derived nasal spray Spravato for treatment-resistant depression in March of 2019. Since then, ketamine has been investigated as a helpful treatment for depression, PTSD , anxiety , and slow news days. Recently, there was a major scientific breakthrough in understanding ketamine’s mechanism of action . Last month, Field Trip, a chain of ketamine clinics, was listed on the Nasdaq. Plus, ketamine clinics have been popping up like Starbucks in major urban areas.

Ketamine is a safe and effective form of therapy and, possibly, the first proverbial “drip” in an eventual waterfall of psychedelic-assisted therapy options. Regardless, it's a watershed moment for this novel therapy.

What Is Ketamine Therapy?

Ketamine is a dissociative anesthetic, considered by some to have psychedelic properties. It is thought to affect the glutamate neurotransmitter in the brain, improving neuroplasticity and interrupting ruminative patterns such as those found with depression. Ketamine therapy entails an intake session with a therapist, then several “sessions” in which ketamine is administered, then integration and follow-up meetings with a therapist. Ketamine can be administered through nasal sprays, lozenges, intramuscular injections, or intravenous infusions.

So the question remains: should you try it? To answer that question, here are 6 others:

What’s Bothering You?

If you have treatment-resistant depression, then this treatment might break through that resistance. Ketamine has also been found effective in combating PTSD and anxiety.

If your depression isn’t “treatment-resistant” because you have yet to treat it, you may want to consider conventional antidepressants first. They have been studied more and longer than ketamine has been studied. Plus SSRIs are likely less expensive. However, they take weeks to start working, if at all. They’re only about 20 percent more effective than a placebo and they come with their own lengthy list of side effects.

Ketamine is both short-acting and fairly long-lasting. What does that mean? It means that the effects are felt within minutes and may last for a week to a month. One 2019 study found the heightened effects of ketamine started within minutes and lasted for at least a month after the session. But a different study from that same year found that the effects of a placebo and conventional antidepressants caught up to ketamine’s effects after seven days. So there is a range. But it’s a safe bet that ketamine offers some bang for your buck—if by “bang” you mean fairly stable relief from mental anguish.

If, however, you have ever suffered from psychosis , schizophrenia, mania , or paranoia , please be aware that ketamine may not be for you. There’s a reason ketamine has been considered a “ schizophrenomimetic .” That’s not just an award-winning spelling bee word, it’s the name for a drug that can mimic schizophrenia-like mental conditions.

Are You Prone to Addiction?

You might think that an affirmative response to this question would preclude you from being a good candidate. But in fact, ketamine may actually be a good treatment for addiction . Two clinical trials showed that ketamine reduced the chance of relapse for cocaine addicts and alcoholics. Ketamine has shown positive results in treating nearly every kind of addiction—except for addictions to ketamine, of course. (Shockingly, the treatment for ketamine addiction is not more ketamine.)

How Risk Intolerant Are You?

Currently, there are no long-term studies about the effects of ketamine as opposed to many conventional antidepressants. Also, ketamine is not 100 percent effective. But then again, literally no treatment is 100 percent effective at curing depression—except perhaps puppies (but this is personal conjecture as no clinical studies have been done yet).

There are also some concerns over risks to the liver, bladder, and kidney . Ketamine can increase heart rate and blood pressure. So people with issues like hypertension may want to steer clear. It’s really a question for your primary care doctor, not an internet blogger, no matter how informative and entertaining she might be.

Are You Afraid of Needles?

Intravenous Infusions are by far the most commonly used and most commonly studied method for administering ketamine. This is because the dosage can be extremely carefully controlled and the journey can be stopped at any moment. The drip controls the trip.

Intramuscular injections are delivered into the thick muscles of your arm, hip, thigh, or if you want the real veterinary clinic feel, the buttocks. With IM infusions , ketamine is administered all at once and cannot be titrated down once injected. IM infusions cannot be as easily mixed with medicines to combat nausea and increased blood pressure.

There are also lozenges and Spravato, the nasal spray which uses esketamine , to consider. Both are administered under supervision (either in an office or remotely on Zoom). These are cheaper alternatives since they do not require special equipment nor a physician trained in anesthesiology. They’re also convenient since patients may even administer the treatment at home themselves. However, both provide relatively lower dosage than the infusion route due to imprecise administration.

Whichever method you’re considering, by far, the most important part of the process is the role played by a mental health professional. Whether this is a psychiatrist, therapist, or integration coach, make sure this is an individual you feel safe around.

How Much Are You Willing to Spend?

Take a deep breath. Assuming you don’t have a chronic pain syndrome, there is a very high chance that insurance will not cover ketamine therapy. Infusions may set you back several thousand dollars but it will include a half dozen infusions sessions, an intake, integration sessions, and follow-ups. The nasal spray Spravato can cost from $590 to $885 per treatment session. But how many treatment sessions are needed is up for debate. Lozenges (administered in the office or monitored remotely over Zoom) can cost about a thousand dollars for 1-6 sessions depending on where you go.

All of the options have a range but all will cost at least several hundred dollars. Unfortunately, the field is new and speculative and therefore, draws many hucksters. Make sure to take time to research your clinic and read any reviews if available.

What Else Should You Know?

Ketamine therapy is as much (if not more) about the “therapy” than it is about the “ketamine.” Make sure you’re working with a clinician you trust and make sure to see an integration therapist with whom you share a connection. Integration is the process of talking with a therapist after a psychedelic or psychoactive session in order to glean meaningful therapeutic insight. Ketamine is a novel and exciting part of the treatment but it’s the therapy that can really lead to lasting change beyond the neural rewiring.

Sarah Rose Siskind is a science comedy writer based in New York City.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Sticking up for yourself is no easy task. But there are concrete skills you can use to hone your assertiveness and advocate for yourself.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

Ketamine’s Catch-22

The drug has a hard-partying past—and a promising future in treating depression.

/media/cinemagraph/2024/08/21/03_Ketamin_animation_R8Article.mp4)

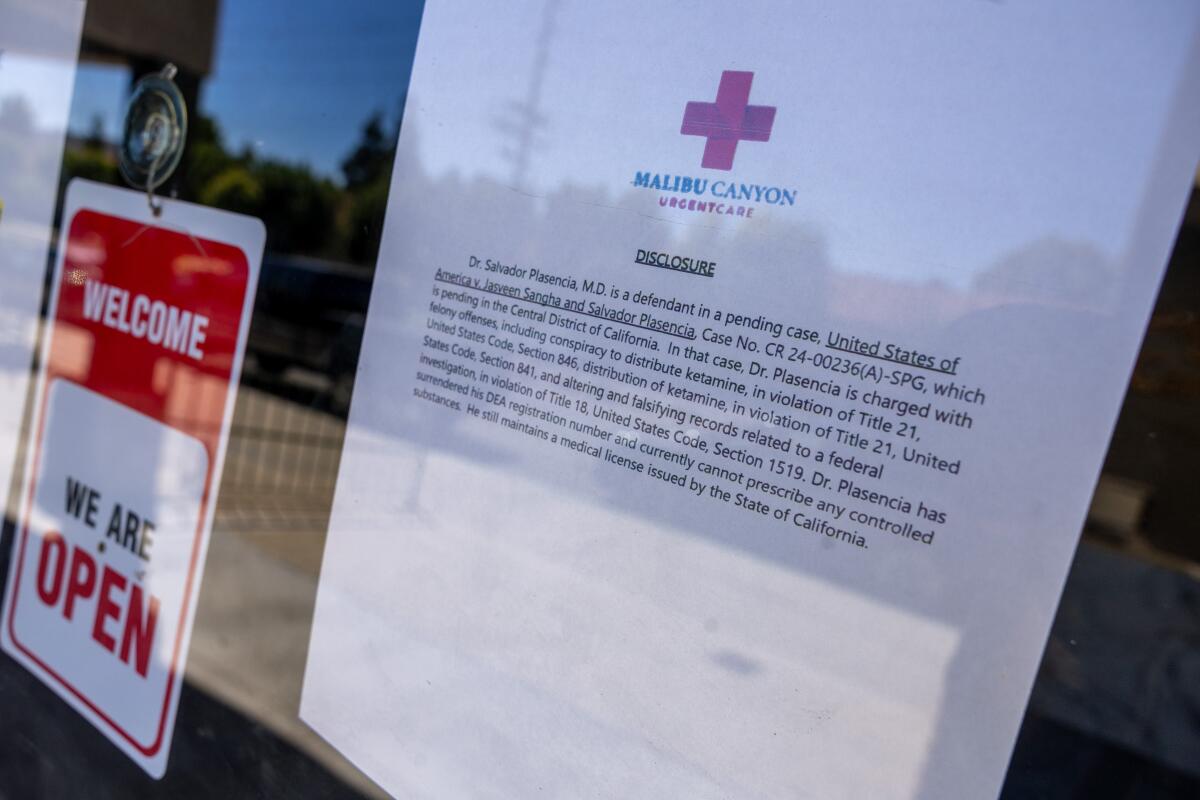

Last week, five people were charged with providing the ketamine that led to actor Matthew Perry’s death. It’s the latest news in a saga that has renewed questions over ketamine’s dual role as a promising depression treatment and an illicit drug.

Questions about ketamine are now all the more relevant because of a pandemic-era decision that allows doctors to prescribe the drug online—transforming the way Americans access and maintain prescriptions for controlled substances.

What role does ketamine have to play in the future of depression treatment now that the prescribing landscape has changed?

This is the third and final episode of Scripts , a new three-part miniseries from Radio Atlantic about the pills we take for our brains and the stories we tell ourselves about them.

Listen to the story here:

Subscribe here: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | YouTube | Overcast | Pocket Casts

The following is a transcript of the episode:

Hanna Rosin: This is Radio Atlantic . I’m Hanna Rosin.

Today we have the third and final episode in our series exploring psychotropic meds and the cultural stories surrounding them. In those early, uncertain days of the pandemic, the government made a decision—a decision that is proving very hard to walk back and that transformed how we access these drugs, how doctors prescribe them, and how we stay on them.

This week, a story about ketamine and about the fallout of that decision. Reporter Ethan Brooks will take it from here.

Ethan Brooks: Okay, I’m going to start with this doctor. His name is Scott Smith, and his story starts back before the pandemic. Smith is working in Mount Pleasant, South Carolina, as a family doctor—so sick kids, high blood pressure, all sorts of things.

One day he’s driving to work, listening to the radio, and NPR is airing a story about ketamine as a treatment for depression.

Scott Smith: And as I was driving to work and I heard them talking about that, I said out loud, That’s the dumbest thing I’ve ever heard of. Ketamine would never help anybody for depression .

Brooks: You said that out loud?

Smith: Yeah, to myself as I was driving because it just was ludicrous.

Brooks: This felt ludicrous because, for Smith, that’s just not what ketamine was for. For him it was as an anesthetic, something you might give to a kid who needs stitches on their tongue, get them to quit squirming. The way it functioned, as he understood it, was to separate the mind from the body.

For other people, ketamine is a party drug, going by names like K, Special K, and, according to the DEA, “Super Acid.” I haven’t heard that one before.

But recently, ketamine’s new gig is as a depression treatment, and a promising one—promising because it works fast, which is a useful feature for people who are suicidally depressed. And it works well for patients for whom other depression treatments don’t work.

Ketamine for depression is often prescribed off-label. And in 2019, the FDA approved an on-label treatment called Spravato, which is a nasal spray. It’s the first genuinely new, FDA-approved depression treatment in 50 years.

After Scott Smith heard that story on the radio, he did some research. And before long, he was a believer.

Smith: I asked myself, Wait a minute. Why has nobody told me about how powerful this treatment is? And why isn’t this being used?

Brooks: So Scott Smith, when he learned all this, felt, in a way, offended that we had been sitting on this drug for so many years, that so many people, including people really close to him, had been struggling with severe depression and that ketamine wasn’t an option that was available to them.

Smith: It was in my face that this was real, and I couldn’t deny it. I couldn’t deny it. To deny it, to me, would mean being a bad doctor. This situation had been presented to me by the universe. My best friend killed himself.

There was no way I was going to let this pass by.

Brooks: Have you felt that before? Like, is this the first time that’s happened?

Smith: That was the first time it overwhelmed me.

Brooks: Smith wanted to get ketamine to as many patients as he could who needed it. So he made a bold decision: He starts his own practice, one that serves both ketamine patients and his normal family-practice patients. He rents an office with two completely separate waiting rooms, so you could be sitting in one waiting room and totally unaware that the other exists. The sign on the door to the first waiting room said smith family, md. The sign on the door to the other room said ketamine treatment services. Scott Smith was behind both doors.

The practice did well. Patients filled up both waiting rooms. And maybe Smith would have liked to treat more patients, but it was a brick-and-mortar office, so that was that. And then the pandemic came, and everything changed.

Okay, so it’s March 20, 2020. To set the scene, this is nine days after the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a pandemic. This is the same day Governor Cuomo issued a stay-at-home order for all New Yorkers, United announced it will cut down international flights by 95 percent, and the DEA made an announcement: Given the circumstances, doctors no longer had to see patients in person—at all—to prescribe controlled substances.

And this decision, I’d like to submit, is among the most enduring and consequential policy decisions of the pandemic. Before this change, with few exceptions, if you wanted a controlled substance—amphetamine, Suboxone, ketamine, Xanax, testosterone—you needed, at some point, to see a doctor in person.

After the March 2020 change, that in-person barrier was gone. It became easier to get prescribed and easier to stay prescribed. And this, especially in a pandemic, saved lives. But something else happened, too.

The way we access and maintain medications underwent a fundamental shift. The new policy brought us into a new era, one where patients have a lot more power—the power to diagnose and treat ourselves without leaving the room.

Brooks: From 2020 to 2022, one study found a tenfold increase in telehealth visits. Americans, as we’ve discussed, started taking a lot more psychiatric medications, and the worlds of venture capital and startups saw an opportunity: psychiatry at a scale that would have been impossible before. The money poured in, and before long, the environment resulting from this confluence of demand, policy, and money had a name.

I’ll just read a few recent headlines here: “New Mental Health Clinics Are a Wild West,” “Adult ADHD Is the Wild West of Psychiatry,” “The Wild West of Online Testosterone Prescribing,” “The Wild West of Off-Brand Ozempic,” “The ‘Wild West’ of Ketamine Treatment.”

You get it—a Wild West, a new world of access and autonomy for patients and for doctors. So Scott Smith—half family-medicine doctor, half ketamine doctor—sees these changes and decides to go west.

Smith: I went all in. I went all in. I became licensed in 48 states.

Brooks: Smith closes the office with two waiting rooms and builds a new practice from the ground up. Now he would only provide ketamine treatment, mostly in the form of off-label, low-dose ketamine lozenges.

Smith: In this practice, every single patient is being treated with the same medicine. The treatment protocol that we’re giving these patients is the same, for every single patient.

It’s like a Baskin-Robbins store that only serves vanilla ice-cream cones. How fast would a Starbucks run that only sold coffee with cream and sugar? That’s it.

Brooks: I started pointing out to Smith that comparing ketamine, a Schedule III controlled substance, to ice cream or to coffee with cream and sugar might give the wrong impression.

And as he clarified his vision, I realized it wasn’t “drugs as candy” that he was really going for or treatment as fast food. What he had in mind was all the things fast-food restaurants do well: efficiency, specialization.

And in a country where someone dies by suicide every 11 minutes, maybe fast-food-style efficiency, applied to a fast-acting depression treatment, isn’t so bad.

Brooks: In Smith’s practice, the problem could be PTSD, anxiety, depression. The solution would be ketamine, ketamine, ketamine.

Smith: I was taking care of about a thousand patients in a pool and, at the peak, it was around 1,500 patients.

Brooks: The more I talked to Smith—and for reasons that will become clear a bit later—I wanted to know: Who were Smith’s 1,500 patients? I also wondered if his patients might be more into the “Super Acid” side of ketamine than the depression treatment.

After all, ketamine can be dangerous. There’s an FDA warning that includes stuff like urinary tract and bladder problems. But also; respiratory depression.The autopsy for Matthew Perry, who played Chandler Bing in Friends , determined that he died from the “acute effect of ketamine.”

I started calling Smith’s patients just a few months after Perry’s death. And I want to just introduce you to two here.

Willow: Good afternoon.

Brooks: Willow, a nurse in Tennessee. I’m going to use a nickname to protect her privacy.

Johannah Haney: Hi. This is Johannah.

Brooks: And Johannah Haney, a writer in Boston. And I want to tell their stories because they help explain the profound positives that came with the 2020 rule change and, also, the risks inherent in that new Wild West.

Haney: Nobody starts with ketamine treatment, you know what I mean? It’s just like, this is sort of the last stop.

If I wasn’t going to get relief, I just wanted it to be over and done. And if you think about being on an airplane, and you’re just so restless, and all you want is to be at this final destination, and, you know, you’re uncomfortable, and you’re bored, and you’re just like—you know that feeling that you get on a plane? It’s how my life felt to me.

Brooks: Johannah had been struggling with depression for years, had tried all the usual depression treatments—SSRIs, anti-anxiety medications, antipsychotics—some of which would work for a while, until they didn’t.

There was one that did work well for her.

Haney: But it was affecting the muscles in my mouth. So as time wore on, you couldn’t understand my speech anymore, which was kind of a big problem.

Brooks: Willow, the nurse, struggled with the usual depression meds, too.

Willow: I tried Prozac. I tried Paxil. I tried Wellbutrin. And nothing was working.