A history of time travel: the how, the why and the when of turning back the clock

Pop on Aqua's 'Turn Back Time' and settle in

For most of human history, the world didn’t change very quickly. Until the 1700s, kids could largely expect their lives to be similar to their parents, and that their children would have an experience very similar to their own, too. There were obviously changes in how humans lived over longer stretches of time, but nothing that even different generations could easily observe.

My first introduction to science fiction was Valérian and Laureline. I was ten years old. Every Wednesday there was a magazine called Pilote in France, and there was two pages of Valerian every week. It was the first time I’d seen a girl and a guy in space, agents travelling in time and space. That was amazing.

The past is written. The present? We have to deal with it. But the future is a white page. So I don’t understand why people on this white page are putting all this darkness.

God! Let’s have some color! Let’s have some fun! Let’s at least imagine a better world. Maybe we won’t be able to do it, but we have to try.

The industrial revolution changed all of this. For the first time in human history, the pace of technological change was visible within a human lifespan.

It is not a coincidence that it was only after science and technological change became a normal part of the human experience, that time travel became something we dreamed of.

Time travel is actually somewhat unique in science fiction. Many core concepts have their origins earlier in history.

The historical roots of the concept of a 'robot' can be seen in Jewish folklore for example: Golems were anthropomorphic beings sculpted from clay. In Greek mythology, characters would travel to other worlds, and it's no coincidence that The Matrix features a character called Persephone. But time travel is different.

The first real work to envisage travelling in time was The Time Machine by HG Wells, which was published in 1895.

The book tells the story of a scientist who builds a machine that will take him to the year 802,701 - a world in which ape-like Morlocks are evolutionary descendants of humanity, and have regressed to a primitive lifestyle.

Get daily insight, inspiration and deals in your inbox

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

The book was a product of its time - both in terms of the science played upon (Charles Darwin had only published Origin of the Species 35 years earlier), and the racist attitudes: it is speculated that the Morlocks were inspired by the Morlachs, a real ethnic group in the Balkans who were often characterised as “primitive”.

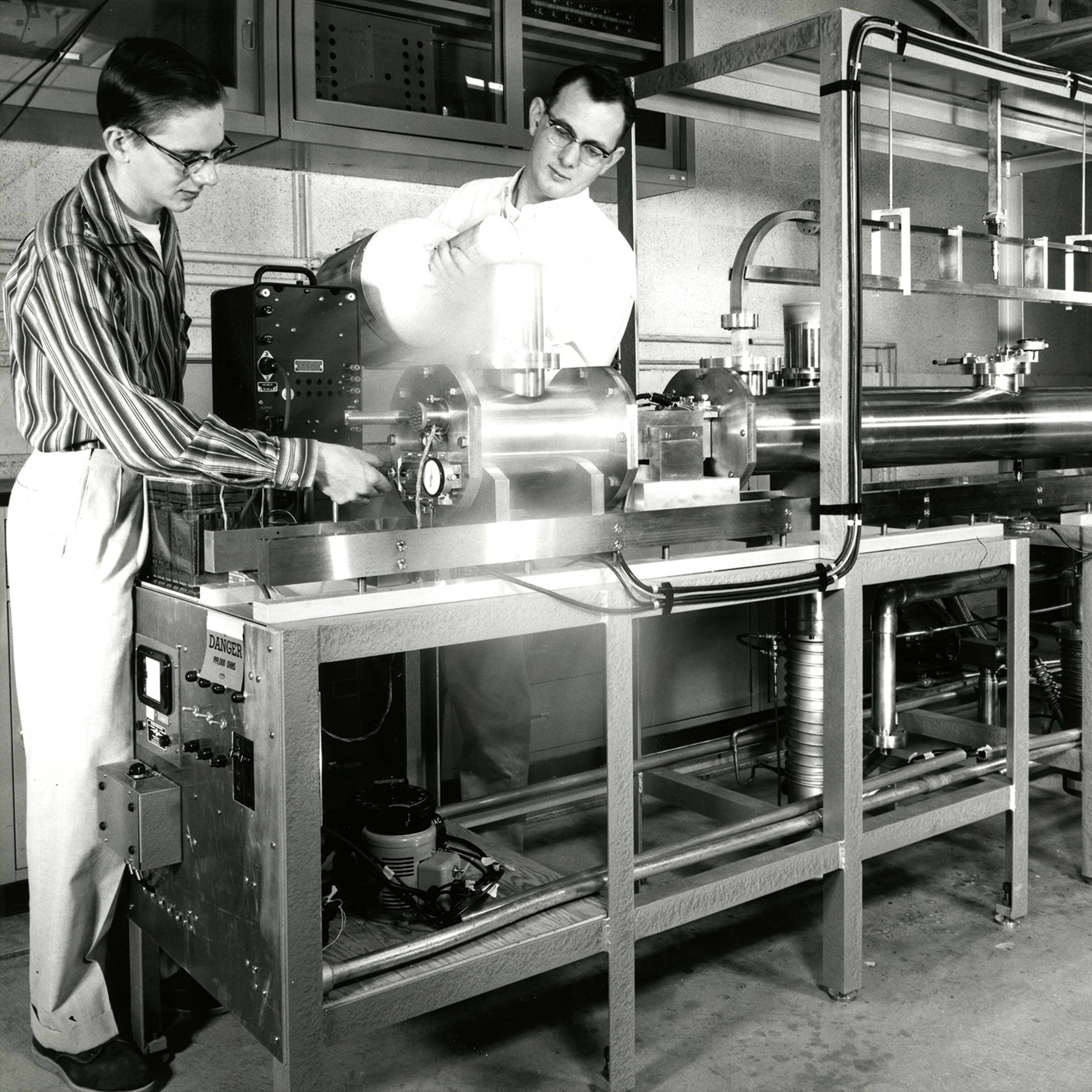

Real science

But of course, this was science fiction - what about science fact? The two have always been closely linked, and during the early days it was no different. In 1907, the physicist Hermann Minkowski first argued that Einstein’s Special Relativity could be expressed in geometric terms as a fourth dimension (to add to our known three) - which is exactly how Wells visualised time travel in his work of fiction.

The development of Special and then General Relativity was significant as it provided the theoretical backbone for how time travel could be conceived in scientific terms. In 1949 Kurt Gödel took Einstein’s work and came up with a solution which as a mathematical necessity included what he called “closed timelike curves” - the idea that if you travel far enough, time will loop back around (like how if you keep flying East, you’ll eventually end up back where you started).

In other words, using what became known as the Gödel Metric, it is theoretically possible to travel between any one point in time and space and any other.

There was just one problem: for Gödel’s theory to be right, the universe would have to be spinning - and scientists don’t believe that it is. So while the maths might make sense, Gödel’s universe does not appear to be the one we’re actually living in. Though he never gave up hope that he might be right: Apparently even on this deathbed, he would ask if anyone has found evidence of a spinning universe. And if he does ever turn out to be right, it means that time travel can happen, and is actually fairly straightforward (well, as far as physics goes anyway).

Since Gödel, scientists have continued to hypothesise about time travel, with perhaps the best known example being tachyons - or particles that move faster than the speed of light (therefore, effectively travelling in time). So far, despite one false alarm at CERN in 2011, there is no evidence that they actually exist.

Chancers and hoaxes

Of course, the lack of real science when it comes to time travel has not stopped some people from claiming to have done it. With the likes of Marty McFly and Doctor Who on the brain, chancers and hoaxers have realised that time travel is immediately a compelling prospect. Here’s a couple of amusing examples.

At the turn of the millennium, when the internet was still in its infancy, forums were captivated by the story of John Titor. Titor claimed he was from the year 2036, and had been sent back in time by the government to obtain an IBM 5100 computer. The thinking appeared to be that by obtaining the computer, the government could find a solution to the UNIX 2038 bug - in which clocks could be reset, Millennium Bug-style, leading to chaos everywhere.

Posting on the 'Time Travel Institute' forums, Titor went into details on how his time machine worked: It was powered by “two top-spin, dual positive singularities”, and used an X-ray venting system. He also gave a potted history of what humanity could expect: A new American civil war in 2004, and World War III in 2015. He also claimed the “many worlds” interpretation of quantum physics was true, hence why he wasn’t violating the so-called “grandfather paradox”.

Titor claimed he was from the year 2036, and had been sent back in time by the government to obtain an IBM 5100 computer.

Okay, so he probably wasn’t a real time traveller, but in the early days of the internet, when anonymity was more commonplace, he truly captured the imaginations of nerdy early adopters who perhaps, just a little bit, hoped that he might be the real thing.

More recently, in 2013, an Iranian scientist named Ali Razeghi claimed to have invented a time machine of sorts. It was supposedly capable of predicting the next 5-8 years for an individual, with up to 98% accuracy. According to The Telegraph , Razeghi said the invention fits into the size of a standard PC case and “It will not take you into the future, it will bring the future to you”. The idea is that the Iranian government could use it to predict future security threats and military confrontations. So perhaps it is time to check in and see if he managed to predict Donald Trump?

So is this the best we can do? Will we ever manage to crack time travel? Some scientists are still sceptical that it could ever be possible. This includes Stephen Hawking, who proposed the 'Chronology Protection Conjecture' – which is what it sounds like. Essentially, he argues that the laws of physics are as they are to specifically make time travel impossible – on all but “submicroscopic” scales. Essentially, this is to protect how causality works, as if we are suddenly allowed to travel back and kill our grandfathers, it would create massive time paradoxes.

Hawking revealed to Ars Technica in 2012 how he had held a party for time travellers, but only sent out invitations after the date it was held. So did the party support his argument that time travel is impossible? Or did he end up spending the evening in the company of John Titor and Doctor Who?

“I sat there a long time, but no one came”, he said, much to our disappointment.

Huge thanks to Stephen Jorgenson-Murray for walking us through some of the more brain-mangling science for this article.

To celebrate the release of Valerian and the City of a Thousand Planets , Luc Besson is today behind the lens at TechRadar. Here’s what we’ve got in store for you:

- Luc Besson presents TechRadar

- From Verne to Valerian: how France became the home of sci-fi

- Luc Besson talks streaming, viral videos and cinema tech

- Star spangled glamour: making space travel cooler than ever before

- A history of time travel: the how, the why and the when

- 20 best sci-fi films on Netflix and Amazon Prime

- Amazing future tech from sci-fi films that totally exist now

Valerian and the City of a Thousand Planets is released in UK cinemas August 2nd, and is out now in the US.

TechRadar Choice Awards 2024 winners: we crown the best tech of the last year

ICYMI: the week's 7 biggest tech stories from Apple's M4 Mac teaser to Alien Romulus releasing on VHS in 2024

A Scary Movie reboot is in the works but you won’t be able to stream it on Paramount Plus anytime soon

Most Popular

- 2 TechRadar's TV of the year is on sale for its lowest price yet in early Black Friday deal

- 3 AI push makes Python the most popular language on GitHub

- 4 How to choose help desk software

- 5 Balatro’s bonkers take on Poker is our Game of the Year because it revitalized the roguelite deckbuilding subgenre

- Newsletters

- Account Activating this button will toggle the display of additional content Account Sign out

Can We Really Travel Back in Time to Change History?

Theoretical physicist paul davies responds to emily st. john mandel’s short story “mr. thursday.”.

Lisa Larson-Walker

Physicist Paul Davies responds to “ Mr. Thursday ,” Emily St. John Mandel’s short story about time travel.

The charm of time travel stories is that the narratives are at once easy to imagine and yet preposterous. As a theoretical physicist with a lifelong research interest in the nature of time, I am often asked by people: Can it really be done? The short answer is, yes—in a sense.

When Albert Einstein published his special theory of relativity in 1905, it made clear that travel into the future is not only possible, but a done deal. One merely has to move fast. Although any degree of relative motion will create temporal mismatches, it is the speed of light that sets the scale. If you travel close to light speed, time gets seriously warped. For example, suppose you want to reach Earth year 2100 in just one year. A yearlong spaceship journey (as experienced by you) at 99.993 per cent of the speed of light would do the trick. You would come back to Earth just one year older to find it was now 2100 at home. In effect, you will have been propelled 82 years into Earth’s future.

There is another way to leap ahead in time: go somewhere with a higher gravitational field. Clocks tick faster in space than on the Earth’s surface, for example. The effect can be directly measured using sensitive clocks but is today commonplace because the GPS satellite-based navigational system must factor in both the speed of the satellites and the lower gravity of orbit. Time warps are real—they’re a matter of practical engineering.

Of course, with existing technology, the time shifts are disappointingly small. Plane travel, for example, creates temporal dislocations measured in a few billionths of a second, which hardly makes for a Dr. Who –style adventure. The other snag is that it is a one-way journey. You can only go forward in time—that is, reach the future sooner. You can’t come back again. Neither can you visit the past, which from the science-fiction standpoint is where the real fascination lies.

Nothing in Einstein’s theory of relativity, however, specifically forbids travel into the past, but physicists are divided over whether to take the possibility seriously. Einstein himself found the notion highly disturbing. One thing on which physicists agree: Going back in time, if not outright impossible, would be stupendously hard to achieve. Proposals abound based on wormholes in space, cosmic strings, and colossal spinning cylinders, but they all seem to necessitate supertechnology and require massive amounts of energy.

Technological barriers and costs notwithstanding, visiting the past would also seem to unleash all manner of paradoxes, which is where the science and the fiction so productively meet. In Emily St. John Mandel’s engaging story, the time traveler, Mr. Thursday, tries to change the past and save a young woman’s life. The tale ends with a rueful discussion in a bar about the consequences of altering anything in history. “Even the smallest thing, you know, you walk through a door ahead of someone …” says the singer. The movie Sliding Doors starring Gwyneth Paltrow examined precisely this theme by presenting two very contrasting narratives flowing from a seemingly minor incident of this sort. In fact, it is easy to imagine more startling examples. It is merely necessary for a person to be displaced by a billionth of a centimeter to alter history, if in so doing a cosmic ray hits a key atom of DNA and induces cancer. If that person were, say, the young Adolf Hitler, the world today would be a very different place.

Causal loop paradoxes might seem to scupper the whole idea of visiting the past, suggesting that any interaction, however tiny, between the time traveler and the past world would be inconsistent with the future from which he had come. But there is a loophole: quantum mechanics.

Quantum mechanics is a description of all of nature, but its effects are most dramatic at the atomic level. The characteristic features are indeterminism and uncertainty: fire an electron at an atom and observe it bounce to the right. Repeat the process under identical conditions and next time it may bounce to the left. It is impossible to know in advance what is going to happen, although the relative probabilities can be accurately calculated. Quantum phenomena imply that the future is undetermined and open.

Less well known is that the inherent fuzziness of quantum mechanics applies to the past as well as the future. Contrary to common sense, there is no fixed and well-defined history stretching back from the present state of the world to the big bang origin of the universe. Rather, there is a multiplicity of contending histories, co-existing in a ghostly superposition of half-realities. Observations made today can nail down certain specific events in the past, like, for example, detecting a cosmic ray may determine its point of origin thousands of years ago. But most of the past, at least at the micro-level, remains not just unknown to us but intrinsically undetermined.

The existence of multiple parallel realities opens the way for time travel. If there is no “fact of the matter” about some aspect of the past, then there is no paradox if a person journeys back in time and resolves something hitherto fuzzy—that is, if the action of a time traveler in the past concretizes a history that would otherwise be left undetermined. It is important to understand that the past cannot be changed, but it can be made less vague, less ambiguous. Intriguingly, experiments with photons ( in the present !) demonstrate how a measurement made at one moment affects the nature of reality at a past moment by resolving its quantum fuzziness, even though the measurement cannot alter the past state. So this weird aspect of quantum mechanics, closely related to what Einstein called “spooky action,” is well established.

But there is a caveat: Whatever the time traveler does in the past, it must be consistent with the state of the world from which she or he has come. Thus it is not possible to go back in time and kill your mother before you were born. But there may be no problem about going back to save a girl from being murdered, and having that girl become your mother, because it forms a self-consistent narrative.

Of course, this means the time traveler does not have unrestricted freedom to do as he pleases. He is hemmed in by the laws of physics. But that is nothing new. After all, I might want to walk on the ceiling, yet the laws of physics forbid it—I’ll simply fall. When causal loops are involved, the restrictions on what is or is not possible will be more severe. What would happen if you tried to kill your mother in the past? Would the knife fall down? Would you simply be unable to lift your arm? Many things could go wrong. But there is nothing strictly paradoxical about someone being part of his own past. So Mr. Thursday may not be able to prevent the accident, but he might have been able to exploit quantum fuzziness to tweak the details of how it happened.

According to Mr. Thursday, time travel would eventually become illegal. But it’s the laws of physics, not the laws of humans, that ensure the universe remains rational, even if it is indeterministic.

This article is part of Future Tense , a collaboration among Arizona State University , New America , and Slate . Future Tense explores the ways emerging technologies affect society, policy, and culture. To read more, follow us on Twitter and sign up for our weekly newsletter .

Time travel could be possible, but only with parallel timelines

Assistant Professor, Physics, Brock University

Disclosure statement

Barak Shoshany does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Brock University provides funding as a member of The Conversation CA-FR.

Brock University provides funding as a member of The Conversation CA.

View all partners

Have you ever made a mistake that you wish you could undo? Correcting past mistakes is one of the reasons we find the concept of time travel so fascinating. As often portrayed in science fiction, with a time machine, nothing is permanent anymore — you can always go back and change it. But is time travel really possible in our universe , or is it just science fiction?

Read more: Curious Kids: is time travel possible for humans?

Our modern understanding of time and causality comes from general relativity . Theoretical physicist Albert Einstein’s theory combines space and time into a single entity — “spacetime” — and provides a remarkably intricate explanation of how they both work, at a level unmatched by any other established theory. This theory has existed for more than 100 years, and has been experimentally verified to extremely high precision, so physicists are fairly certain it provides an accurate description of the causal structure of our universe.

For decades, physicists have been trying to use general relativity to figure out if time travel is possible . It turns out that you can write down equations that describe time travel and are fully compatible and consistent with relativity. But physics is not mathematics, and equations are meaningless if they do not correspond to anything in reality.

Arguments against time travel

There are two main issues which make us think these equations may be unrealistic. The first issue is a practical one: building a time machine seems to require exotic matter , which is matter with negative energy. All the matter we see in our daily lives has positive energy — matter with negative energy is not something you can just find lying around. From quantum mechanics, we know that such matter can theoretically be created, but in too small quantities and for too short times .

However, there is no proof that it is impossible to create exotic matter in sufficient quantities. Furthermore, other equations may be discovered that allow time travel without requiring exotic matter. Therefore, this issue may just be a limitation of our current technology or understanding of quantum mechanics.

The other main issue is less practical, but more significant: it is the observation that time travel seems to contradict logic, in the form of time travel paradoxes . There are several types of such paradoxes, but the most problematic are consistency paradoxes .

A popular trope in science fiction, consistency paradoxes happen whenever there is a certain event that leads to changing the past, but the change itself prevents this event from happening in the first place.

For example, consider a scenario where I enter my time machine, use it to go back in time five minutes, and destroy the machine as soon as I get to the past. Now that I destroyed the time machine, it would be impossible for me to use it five minutes later.

But if I cannot use the time machine, then I cannot go back in time and destroy it. Therefore, it is not destroyed, so I can go back in time and destroy it. In other words, the time machine is destroyed if and only if it is not destroyed. Since it cannot be both destroyed and not destroyed simultaneously, this scenario is inconsistent and paradoxical.

Eliminating the paradoxes

There’s a common misconception in science fiction that paradoxes can be “created.” Time travellers are usually warned not to make significant changes to the past and to avoid meeting their past selves for this exact reason. Examples of this may be found in many time travel movies, such as the Back to the Future trilogy.

But in physics, a paradox is not an event that can actually happen — it is a purely theoretical concept that points towards an inconsistency in the theory itself. In other words, consistency paradoxes don’t merely imply time travel is a dangerous endeavour, they imply it simply cannot be possible.

This was one of the motivations for theoretical physicist Stephen Hawking to formulate his chronology protection conjecture , which states that time travel should be impossible. However, this conjecture so far remains unproven. Furthermore, the universe would be a much more interesting place if instead of eliminating time travel due to paradoxes, we could just eliminate the paradoxes themselves.

One attempt at resolving time travel paradoxes is theoretical physicist Igor Dmitriyevich Novikov’s self-consistency conjecture , which essentially states that you can travel to the past, but you cannot change it.

According to Novikov, if I tried to destroy my time machine five minutes in the past, I would find that it is impossible to do so. The laws of physics would somehow conspire to preserve consistency.

Introducing multiple histories

But what’s the point of going back in time if you cannot change the past? My recent work, together with my students Jacob Hauser and Jared Wogan, shows that there are time travel paradoxes that Novikov’s conjecture cannot resolve. This takes us back to square one, since if even just one paradox cannot be eliminated, time travel remains logically impossible.

So, is this the final nail in the coffin of time travel? Not quite. We showed that allowing for multiple histories (or in more familiar terms, parallel timelines) can resolve the paradoxes that Novikov’s conjecture cannot. In fact, it can resolve any paradox you throw at it.

The idea is very simple. When I exit the time machine, I exit into a different timeline. In that timeline, I can do whatever I want, including destroying the time machine, without changing anything in the original timeline I came from. Since I cannot destroy the time machine in the original timeline, which is the one I actually used to travel back in time, there is no paradox.

After working on time travel paradoxes for the last three years , I have become increasingly convinced that time travel could be possible, but only if our universe can allow multiple histories to coexist. So, can it?

Quantum mechanics certainly seems to imply so, at least if you subscribe to Everett’s “many-worlds” interpretation , where one history can “split” into multiple histories, one for each possible measurement outcome – for example, whether Schrödinger’s cat is alive or dead, or whether or not I arrived in the past.

But these are just speculations. My students and I are currently working on finding a concrete theory of time travel with multiple histories that is fully compatible with general relativity. Of course, even if we manage to find such a theory, this would not be sufficient to prove that time travel is possible, but it would at least mean that time travel is not ruled out by consistency paradoxes.

Time travel and parallel timelines almost always go hand-in-hand in science fiction, but now we have proof that they must go hand-in-hand in real science as well. General relativity and quantum mechanics tell us that time travel might be possible, but if it is, then multiple histories must also be possible.

- Time travel

- Theoretical physics

- Time machine

- Albert Einstein

- Listen to this article

- Time travel paradox

Commissioning Editor Nigeria

Subject Coordinator PCP2

Professor in Physiotherapy

Postdoctoral Research Associate

Editorial Internship

Time Travel Probably Isn't Possible—Why Do We Wish It Were?

Time travel exerts an irresistible pull on our scientific and storytelling imagination.

Since H.G. Wells imagined that time was a fourth dimension —and Einstein confirmed it—the idea of time travel has captivated us. More than 50 scientific papers are published on time travel each year, and storytellers continually explore it—from Stephen King’s JFK assassination novel 11/22/63 to the steamy Outlander television series to Woody Allen’s comedy Midnight in Paris . What if we could travel back in time, we wonder, and change history? Assassinate Hitler or marry that high school sweetheart who dumped us? What if we could see what the future has in store?

These are some of the ideas that bestselling author James Gleick explores in his thought-provoking new book, Time Travel: A History. Speaking from his home in New York City, he recalls how Stephen Hawking once sent out invitations to a party that had already taken place ; why the Chinese government has branded time travel as “incorrect” and “frivolous” ; and how the idea of time travel is, ultimately, about our desire to defeat death.

Let’s cut right to the chase: What is time?

Oh, no, you didn’t! [ Laughs. ] In A.D. 400, St. Augustine said—and many people have said the same thing since, either quoting him consciously or unconsciously—“What, then, is time? If no one asks me, I know. If I wish to explain it to one that asks, I know not.” I think that is actually not a quip, but quite profound.

The best way to understand time is to recognize that we actually are very sophisticated about it. Over the past century-plus, we’ve learned a great deal. The physicist John Archibald Wheeler said, “Time is nature’s way to keep everything from happening all at once.” If you look it up in a dictionary, you get stuff like, “The general term for the experience of duration.” But that’s just completely punting because what is duration ?

I try to steer away from aphorisms and dictionary definitions, just to say two things. First, that we have a lot of contradictory ways of talking about time. We think of time as something we waste, spend, or save, as if it’s a quantity. We also think of time as a medium we are passing through every day, a river carrying us along. All of these notions are aspects of a complicated subject that has no bumper sticker answer.

When does the idea of time travel first appear in the West? And how did it impact popular culture?

I assumed, as a person who always read sci-fi a lot when I was a kid, that time travel is an obvious idea we’re born knowing and fantasizing about. And that it must always have been part of human culture, that there must be time travel Greek myths and Chinese legends. But there aren’t! Time travel turns out to be a very new idea that essentially starts with H.G. Wells’s 1895 novel, The Time Machine . Before that nobody thought of putting the words time and travel together. The closest you can come before that is people falling asleep, like Rip Van Winkle, or fantasies like Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol .

YEAR-LONG ADVENTURE for every explorer on your list

The beginning of my book is an attempt to answer the question, “Why? Why not before? Why suddenly at the end of the 19 th century was it possible— necessary— for people to dream up this crazy fantasy?” Even though it’s H.G. Wells who does it, people pick up his ball very quickly and run with it. You find it in American science fiction that started appearing in pulp magazines in the 1920s and 1930s, or in the great new modernist literature of Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time , James Joyce, and Virginia Woolf.

All these writers were suddenly making time their explicit subject, twisting time in new ways, inventing new narrative techniques to deal with time, to explore the vagaries of memory or the way our consciousness changes over time.

In 1991, Stephen Hawking wrote a paper called “Chronology Protection Conjecture , ” in which he asked: If time travel is possible, why are we not inundated with tourists from the future? He has a point, doesn’t he?

Yes! He even scheduled a party and sent out an invitation inviting time travelers to come to a party that had taken place in the past. Then he observed that none of them had shown up. [Laughs.] Hawking is one of these physicists who love playing with the idea of time travel. It’s irresistible because it’s so much fun! When he talks about the paradoxes of time travel it’s because he’s reading the same science fiction stories as the rest of us.

The paradoxes started appearing in magazines aimed mostly at young people in the 1920s. Somebody wrote in and said, “Time travel is a weird idea, because what if you go back in time and you kill your grandfather? Then your grandfather never meets your grandmother and you’re never born.” It’s an impossible loop.

Hawking, like other physicists, decided, “Time is my business. What if we take this seriously? Can we express this in physical terms?” I don’t think he succeeded but what he proposed was that the reason these paradoxes can’t happen is because the universe takes care of itself. It can’t happen because it didn’t happen. That’s the simple way of saying what the chronology protection conjecture is.

How have the Internet and other new technologies changed our perception and experience of time?

We are just beginning to see what the Internet is doing to our perception of time. We are living more and more in this networked world in which everything travels at light speed. We are multitasking and experiencing new forms of simultaneity, so the Internet appears to us as a kind of hall of mirrors. It feels as though we’re embedded in an ever expanding present.

Our sense of the past changes because in some ways the past becomes more vivid than ever. We’re looking at the past on our video screens and it’s just as vivid if the movie is about something that happened 20 years ago, as if it is a live stream. We can’t always tell the difference. On the other hand, the past that’s more distant—and isn’t available in video form—starts to seem more remote and fuzzier. Maybe we are forgetting how to visualize the past from reading histories. We’re entering a new period of time confusion, in which we suddenly find ourselves in what looks like an unending present.

In 2011, the Chinese government issued an extraordinary denunciation of the idea of time travel. What was their beef?

They thought it was corrupting and decadent. It’s a reminder that time travel is neither a simple nor innocent idea. It’s very powerful. It enables us to imagine alternative universes, and this is another line that science fiction writers have explored. What if someone was able to go back in time and kill Hitler?

Time travel is also a powerful way of allowing us to imagine what the future might bring. A lot of futurists nowadays tend to be dystopian. Time travel gives us ways of exploring how the worst tendencies of our current societies could grow even worse. That’s what George Orwell did in 1984 . I imagine the Chinese government doesn’t particularly want the equivalent of 1984 to be published in Beijing. [ Laughs. ]

You May Also Like

What's a leap second—and why is it going away for good?

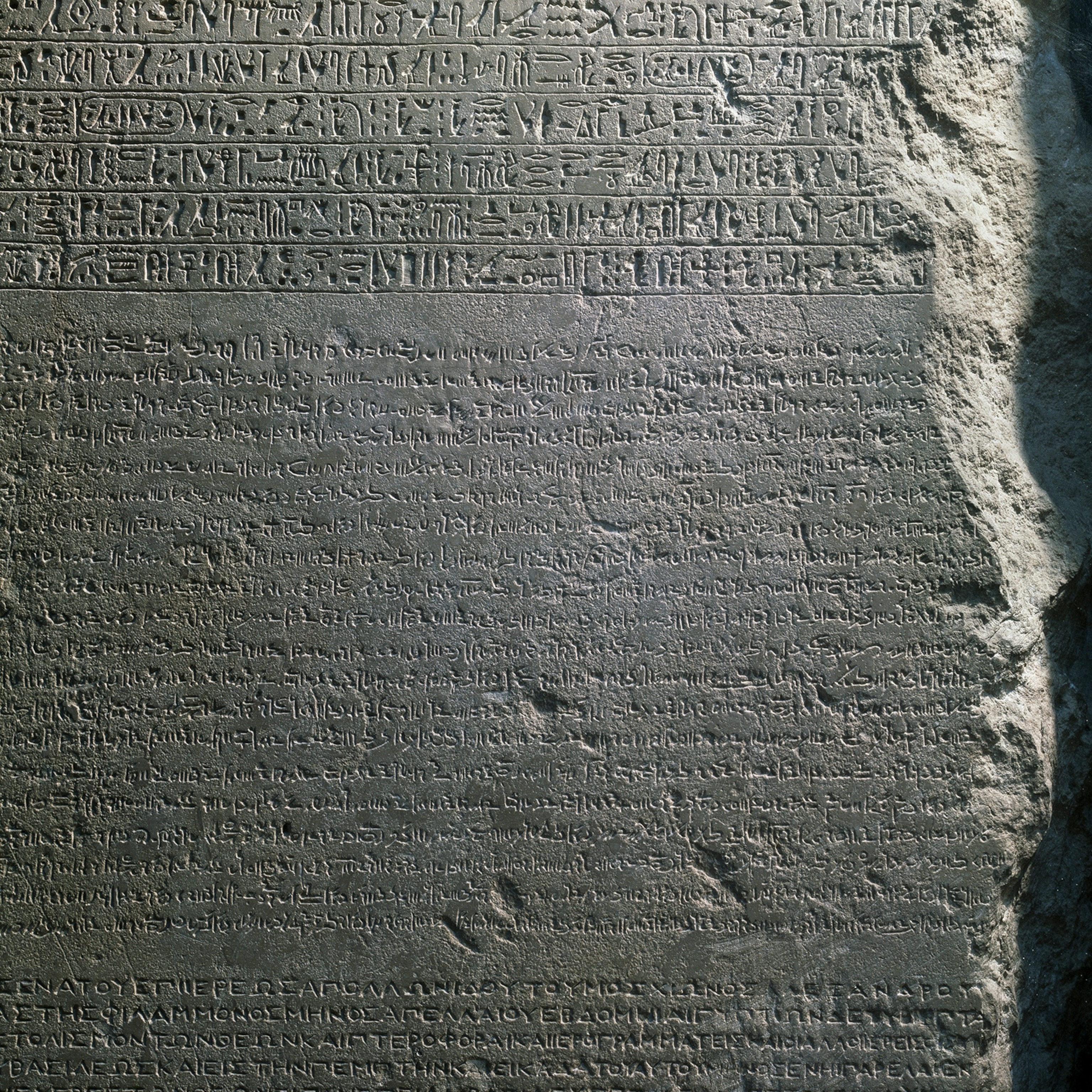

This 2,200-year-old slab bears the world’s first mention of leap year

There’s a better way to wake up. Here’s what experts advise.

More than 50 scientific papers a year are now published on the idea of time travel. why are scientists drawn to the subject.

Scientists live in the same science fictional universe as all the rest of us. Time travel is a sexy and romantic idea that appeals to the physicist as much as it appeals to every teenager. I don’t think scientists are ever going to solve the problem of time travel for us but they still love to talk about wormholes and dark matter.

There’s a fascinating coincidence in the early history that when H.G. Wells needed to set the stage for his time machine hurtling into the future, he decided not to just jump right into his story but set the scene with a framing device—his time traveler lecturing a group of friends on the science of time—in order to justify the possibility of a time machine. His lecture introduces the idea that time is nothing more than a fourth dimension, that traveling through time is analogous to traveling through space. Since we have machines that can take us into any of the three special dimensions, including balloons and elevators, why shouldn’t we have a machine able to travel through the fourth dimension?

A decade later, Einstein burst onto the scene with his theory of relativity in which time is a fourth dimension , just like space. Soon after that, Hermann Minkowski pronounced that, henceforth, we were not going to talk about space and time as separate quantities but as a union of the two, spacetime , a four-dimensional continuum in which the future already exists and the past still exists.

I’m not claiming that Einstein read H.G. Wells 10 years before. But there was something in the air that both scientists and imaginative writers were empowered to visualize time in a new way. Today, that’s the way we visualize it. We’re comfortable talking about time as a fourth dimension.

You quote Ursula K. Le Guin , who writes, “Story is our only boat for sailing on the river of time.” Talk about storytelling and its relationship to time.

One of the things that has happened, along with our heightened awareness of time and its possibilities, is that people who invent narratives have learned very clever new techniques. Literal time travel is only one of them. You don’t actually need to send your hero into the future or into the past to write a story that plays with time in clever new ways. Narrative is also how everybody, not just writers, constructs a vision of our own relationship with time. We imagine the future. We remember the past. When we do that, we’re making up stories.

Psychologists are learning something that great storytellers have known for some time, which is that memory is not like computer retrieval. It’s an active process. Every time we remember something we are remembering it a little bit differently. We’re retelling the story to ourselves.

If time travel is impossible, why do we continue to be so fascinated with the idea?

One of the reasons is we want to go back and undo our mistakes. When you ask yourself, “If I had a time machine, what would I do?” sometimes the answer is, “I would go back to this particular day and do that thing over.” I think one of the great time travel movies is Groundhog Day , the Bill Murray movie where he wakes up every morning and has to live the same day over and over again. He gradually realizes that perhaps fate is telling him he needs to do it over, right. Regret is the time traveler’s energy bar. But that’s not the only motivation for time travel. We also have curiosity about the future and interest in our parents and our children. A lot of time travel fiction is a way of asking questions about what our parents were like, or what our children will be like.

At some point during the four years I worked on this book, I also realized that, in one way or another, every time travel story is about death. Death is either explicitly there in the foreground or lurking in the background because time is a bastard, right? Time is brutal. What does time do to us? It kills us. Time travel is our way of flirting with immortality. It’s the closest we’re going to come to it.

This interview was edited for length and clarity.

Simon Worrall curates Book Talk . Follow him on Twitter or at simonworrallauthor.com .

Related Topics

Why daylight saving time exists—at least for now

Leap year saved our societies from chaos—for now, at least

Primed by expectations – why a classic psychology experiment isn’t what it seemed

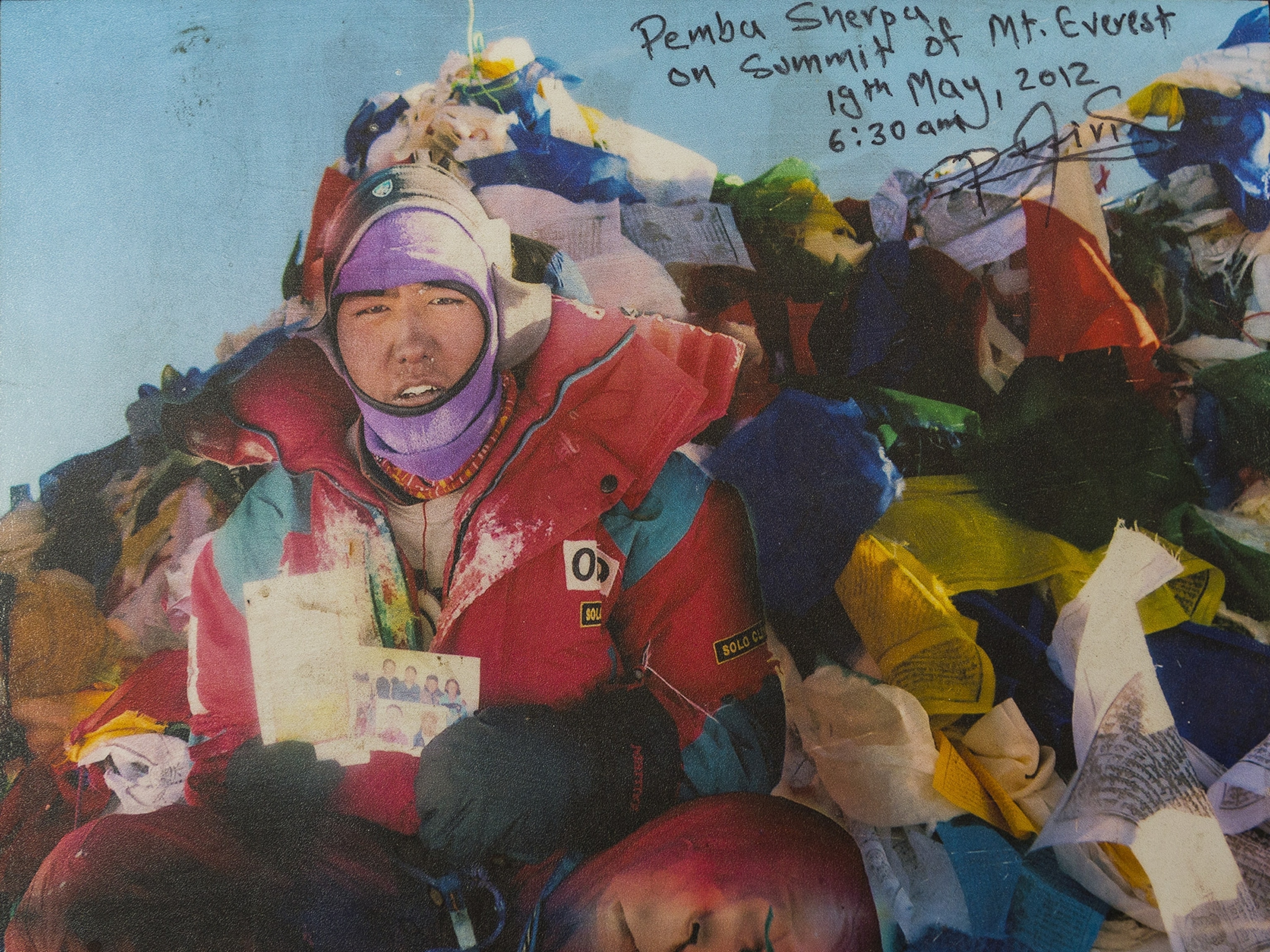

A Year After Everest Disaster, This Sherpa Isn't Going Back

Does eating close to bedtime make you gain weight? It depends.

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information

- Nat Geo Home

- Attend a Live Event

- Book a Trip

- Inspire Your Kids

- Shop Nat Geo

- Visit the D.C. Museum

- Learn About Our Impact

- Support Our Mission

- Advertise With Us

- Customer Service

- Renew Subscription

- Manage Your Subscription

- Work at Nat Geo

- Sign Up for Our Newsletters

- Contribute to Protect the Planet

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

IMAGES

COMMENTS

Time travel is the hypothetical activity of traveling into the past or future. Time travel is a widely recognized concept in philosophy and fiction, particularly science fiction. In fiction, time travel is typically achieved through the use of a hypothetical device known as a time machine. The idea of a time machine was popularized by H. G. Wells's 1895 novel The Tim…

Can We Really Travel Back in Time to Change History? Theoretical physicist Paul Davies responds to Emily St. John Mandel’s short …

The first time travel scene in the 1985 film ‘Back to the Future.’ Introducing multiple histories. But what’s the point of going back in time if you cannot change the past?

What if we could travel back in time, we wonder, and change history? Assassinate Hitler or marry that high school sweetheart who dumped us? What if we could see what the future has in store?

Real-life time travel occurs through time dilation, a property of Einstein’s special relativity. Einstein was the first to realize that time is not constant, as previously believed, but instead slows down as you move faster …

The ability to jump forward and backwards in time has long fascinated science fiction writers and physicists alike. So is it really possible to travel into the past and the future?