TRY OUR FREE APP

Write your book in Reedsy Studio. Try the beloved writing app for free today.

Craft your masterpiece in Reedsy Studio

Plan, write, edit, and format your book in our free app made for authors.

Last updated on Aug 10, 2023

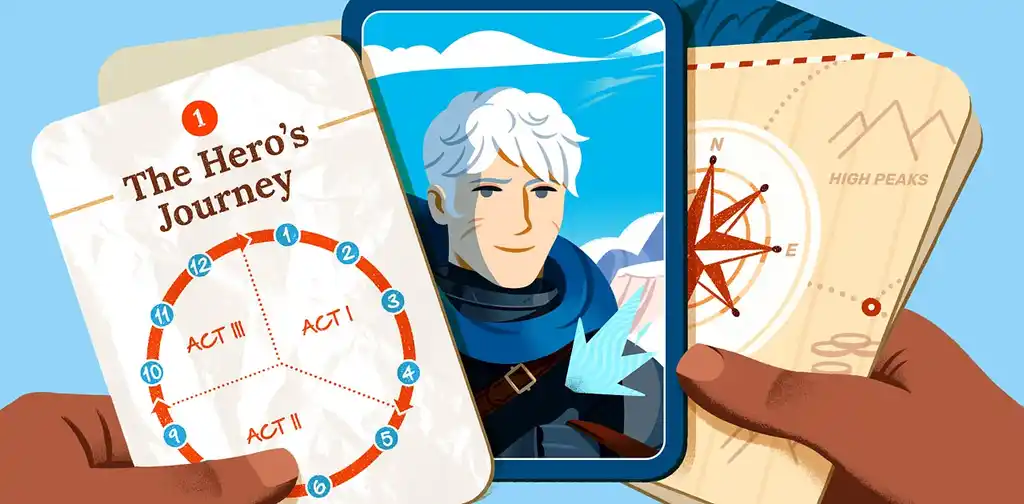

The Hero's Journey: 12 Steps to a Classic Story Structure

About the author.

Reedsy's editorial team is a diverse group of industry experts devoted to helping authors write and publish beautiful books.

About Dario Villirilli

Editor-in-Chief of the Reedsy blog, Dario is a graduate of Mälardalen University. As a freelance writer, he has written for many esteemed outlets aimed at writers. A traveler at heart, he can be found roaming the world and working from his laptop.

The Hero's Journey is a timeless story structure which follows a protagonist on an unforeseen quest, where they face challenges, gain insights, and return home transformed. From Theseus and the Minotaur to The Lion King , so many narratives follow this pattern that it’s become ingrained into our cultural DNA.

In this post, we'll show you how to make this classic plot structure work for you — and if you’re pressed for time, download our cheat sheet below for everything you need to know.

FREE RESOURCE

Hero's Journey Template

Plot your character's journey with our step-by-step template.

What is the Hero’s Journey?

The Hero's Journey, also known as the monomyth, is a story structure where a hero goes on a quest or adventure to achieve a goal, and has to overcome obstacles and fears, before ultimately returning home transformed.

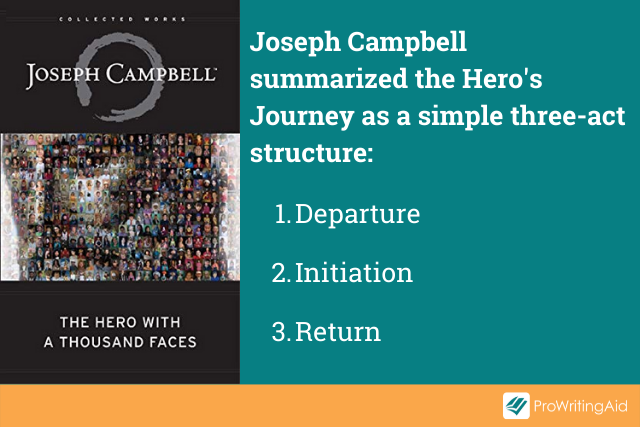

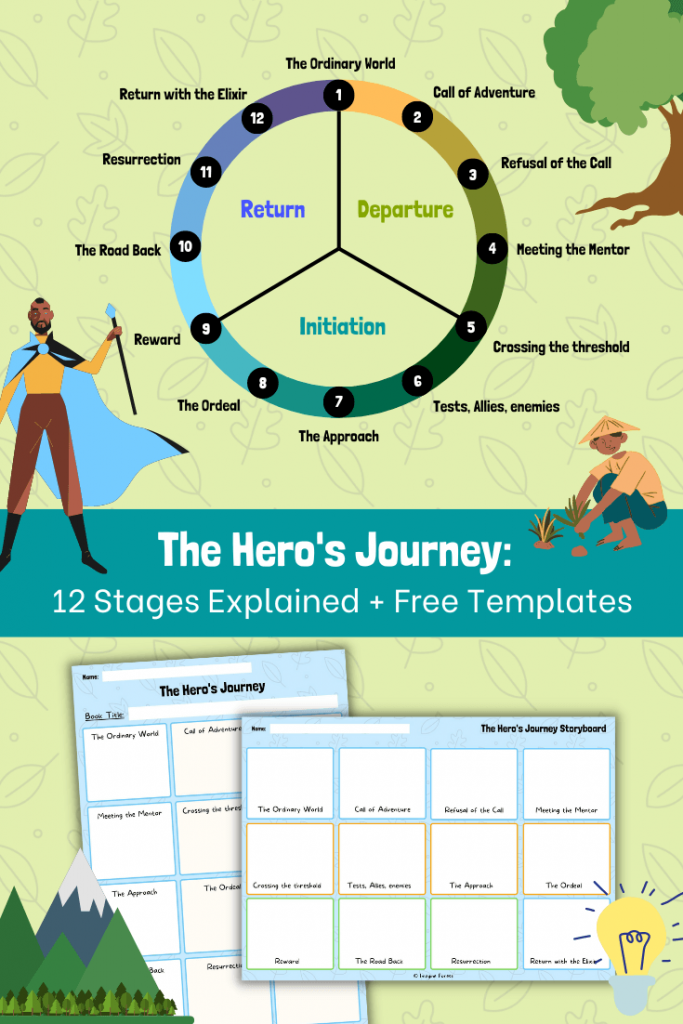

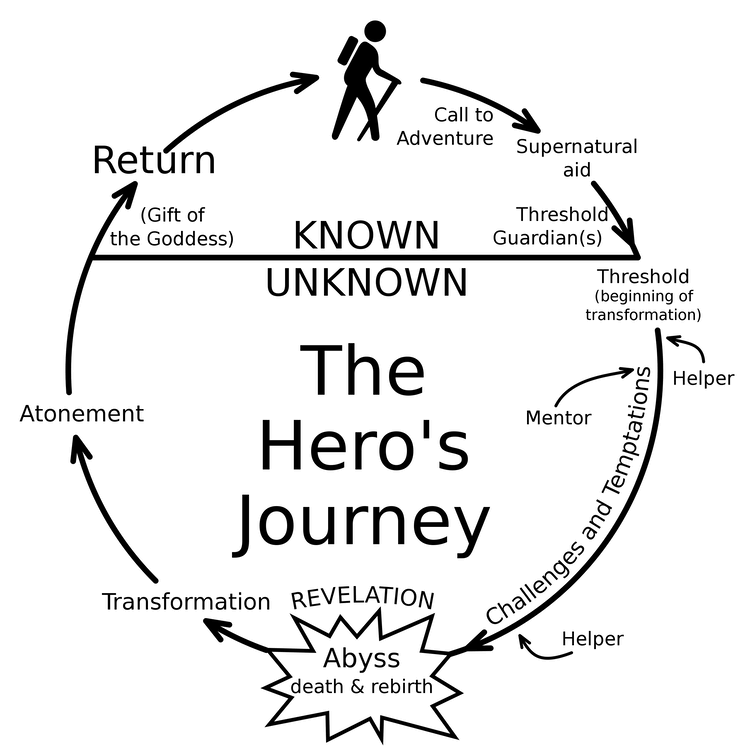

This narrative arc has been present in various forms across cultures for centuries, if not longer, but gained popularity through Joseph Campbell's mythology book, The Hero with a Thousand Faces . While Campbell identified 17 story beats in his monomyth definition, this post will concentrate on a 12-step framework popularized in 2007 by screenwriter Christopher Vogler in his book The Writer’s Journey .

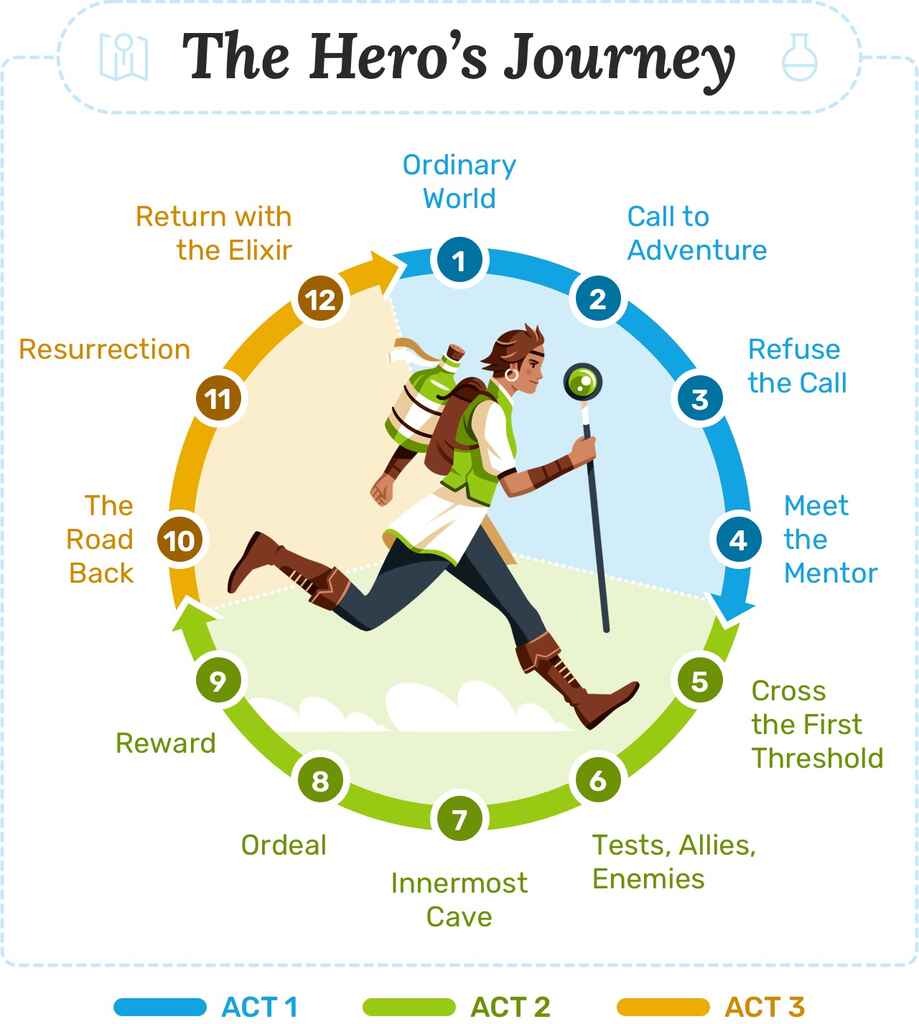

The 12 Steps of the Hero’s Journey

The Hero's Journey is a model for both plot points and character arc development: as the Hero traverses the world, they'll undergo inner and outer transformation at each stage of the journey. The 12 steps of the hero's journey are:

- The Ordinary World: We meet our hero.

- Call to Adventure: Will they meet the challenge?

- Refusal of the Call: They resist the adventure.

- Meeting the Mentor: A teacher arrives.

- Crossing the First Threshold: The hero leaves their comfort zone.

- Tests, Allies, Enemies: Making friends and facing roadblocks.

- Approach to the Inmost Cave: Getting closer to our goal.

- Ordeal: The hero’s biggest test yet!

- Reward (Seizing the Sword): Light at the end of the tunnel

- The Road Back: We aren’t safe yet.

- Resurrection: The final hurdle is reached.

- Return with the Elixir: The hero heads home, triumphant.

Believe it or not, this story structure also applies across mediums and genres. Let's dive into it!

1. Ordinary World

In which we meet our Hero.

The journey has yet to start. Before our Hero discovers a strange new world, we must first understand the status quo: their ordinary, mundane reality.

It’s up to this opening leg to set the stage, introducing the Hero to readers. Importantly, it lets readers identify with the Hero as a “normal” person in a “normal” setting, before the journey begins.

2. Call to Adventure

In which an adventure starts.

The call to adventure is all about booting the Hero out of their comfort zone. In this stage, they are generally confronted with a problem or challenge they can't ignore. This catalyst can take many forms, as Campbell points out in Hero with a Thousand Faces . The Hero can, for instance:

- Decide to go forth of their own volition;

- Theseus upon arriving in Athens.

- Be sent abroad by a benign or malignant agent;

- Odysseus setting off on his ship in The Odyssey .

- Stumble upon the adventure as a result of a mere blunder;

- Dorothy when she’s swept up in a tornado in The Wizard of Oz .

- Be casually strolling when some passing phenomenon catches the wandering eye and lures one away from the frequented paths of man.

- Elliot in E.T. upon discovering a lost alien in the tool shed.

The stakes of the adventure and the Hero's goals become clear. The only question: will he rise to the challenge?

3. Refusal of the Call

In which the Hero digs in their feet.

Great, so the Hero’s received their summons. Now they’re all set to be whisked off to defeat evil, right?

Not so fast. The Hero might first refuse the call to action. It’s risky and there are perils — like spiders, trolls, or perhaps a creepy uncle waiting back at Pride Rock . It’s enough to give anyone pause.

In Star Wars , for instance, Luke Skywalker initially refuses to join Obi-Wan on his mission to rescue the princess. It’s only when he discovers that his aunt and uncle have been killed by stormtroopers that he changes his mind.

4. Meeting the Mentor

In which the Hero acquires a personal trainer.

The Hero's decided to go on the adventure — but they’re not ready to spread their wings yet. They're much too inexperienced at this point and we don't want them to do a fabulous belly-flop off the cliff.

Enter the mentor: someone who helps the Hero, so that they don't make a total fool of themselves (or get themselves killed). The mentor provides practical training, profound wisdom, a kick up the posterior, or something abstract like grit and self-confidence.

Wise old wizards seem to like being mentors. But mentors take many forms, from witches to hermits and suburban karate instructors. They might literally give weapons to prepare for the trials ahead, like Q in the James Bond series. Or perhaps the mentor is an object, such as a map. In all cases, they prepare the Hero for the next step.

GET ACCOUNTABILITY

Meet writing coaches on Reedsy

Industry insiders can help you hone your craft, finish your draft, and get published.

5. Crossing the First Threshold

In which the Hero enters the other world in earnest.

Now the Hero is ready — and committed — to the journey. This marks the end of the Departure stage and is when the adventure really kicks into the next gear. As Vogler writes: “This is the moment that the balloon goes up, the ship sails, the romance begins, the wagon gets rolling.”

From this point on, there’s no turning back.

Like our Hero, you should think of this stage as a checkpoint for your story. Pause and re-assess your bearings before you continue into unfamiliar territory. Have you:

- Launched the central conflict? If not, here’s a post on types of conflict to help you out.

- Established the theme of your book? If not, check out this post that’s all about creating theme and motifs.

- Made headway into your character development? If not, this author-approved template may be useful:

Reedsy’s Character Profile Template

A story is only as strong as its characters. Fill this out to develop yours.

6. Tests, Allies, Enemies

In which the Hero faces new challenges and gets a squad.

When we step into the Special World, we notice a definite shift. The Hero might be discombobulated by this unfamiliar reality and its new rules. This is generally one of the longest stages in the story , as our protagonist gets to grips with this new world.

This makes a prime hunting ground for the series of tests to pass! Luckily, there are many ways for the Hero to get into trouble:

- In Jumanji: Welcome to the Jungle , Spencer, Bethany, “Fridge,” and Martha get off to a bad start when they bump into a herd of bloodthirsty hippos.

- In his first few months at Hogwarts, Harry Potter manages to fight a troll, almost fall from a broomstick and die, and get horribly lost in the Forbidden Forest.

- Marlin and Dory encounter three “reformed” sharks, get shocked by jellyfish, and are swallowed by a blue whale en route to finding Nemo.

This stage often expands the cast of characters. Once the protagonist is in the Special World, he will meet allies and enemies — or foes that turn out to be friends and vice versa. He will learn a new set of rules from them. Saloons and seedy bars are popular places for these transactions, as Vogler points out (so long as the Hero survives them).

7. Approach to the Inmost Cave

In which the Hero gets closer to his goal.

This isn’t a physical cave. Instead, the “inmost cave” refers to the most dangerous spot in the other realm — whether that’s the villain’s chambers, the lair of the fearsome dragon, or the Death Star. Almost always, it is where the ultimate goal of the quest is located.

Note that the protagonist hasn’t entered the Inmost Cave just yet. This stage is all about the approach to it. It covers all the prep work that's needed in order to defeat the villain.

In which the Hero faces his biggest test of all thus far.

Of all the tests the Hero has faced, none have made them hit rock bottom — until now. Vogler describes this phase as a “black moment.” Campbell refers to it as the “belly of the whale.” Both indicate some grim news for the Hero.

The protagonist must now confront their greatest fear. If they survive it, they will emerge transformed. This is a critical moment in the story, as Vogler explains that it will “inform every decision that the Hero makes from this point forward.”

The Ordeal is sometimes not the climax of the story. There’s more to come. But you can think of it as the main event of the second act — the one in which the Hero actually earns the title of “Hero.”

9. Reward (Seizing the Sword)

In which the Hero sees light at the end of the tunnel.

Our Hero’s been through a lot. However, the fruits of their labor are now at hand — if they can just reach out and grab them! The “reward” is the object or knowledge the Hero has fought throughout the entire journey to hold.

Once the protagonist has it in their possession, it generally has greater ramifications for the story. Vogler offers a few examples of it in action:

- Luke rescues Princess Leia and captures the plans of the Death Star — keys to defeating Darth Vader.

- Dorothy escapes from the Wicked Witch’s castle with the broomstick and the ruby slippers — keys to getting back home.

10. The Road Back

In which the light at the end of the tunnel might be a little further than the Hero thought.

The story's not over just yet, as this phase marks the beginning of Act Three. Now that he's seized the reward, the Hero tries to return to the Ordinary World, but more dangers (inconveniently) arise on the road back from the Inmost Cave.

More precisely, the Hero must deal with the consequences and aftermath of the previous act: the dragon, enraged by the Hero who’s just stolen a treasure from under his nose, starts the hunt. Or perhaps the opposing army gathers to pursue the Hero across a crowded battlefield. All further obstacles for the Hero, who must face them down before they can return home.

11. Resurrection

In which the last test is met.

Here is the true climax of the story. Everything that happened prior to this stage culminates in a crowning test for the Hero, as the Dark Side gets one last chance to triumph over the Hero.

Vogler refers to this as a “final exam” for the Hero — they must be “tested once more to see if they have really learned the lessons of the Ordeal.” It’s in this Final Battle that the protagonist goes through one more “resurrection.” As a result, this is where you’ll get most of your miraculous near-death escapes, à la James Bond's dashing deliverances. If the Hero survives, they can start looking forward to a sweet ending.

12. Return with the Elixir

In which our Hero has a triumphant homecoming.

Finally, the Hero gets to return home. However, they go back a different person than when they started out: they’ve grown and matured as a result of the journey they’ve taken.

But we’ve got to see them bring home the bacon, right? That’s why the protagonist must return with the “Elixir,” or the prize won during the journey, whether that’s an object or knowledge and insight gained.

Of course, it’s possible for a story to end on an Elixir-less note — but then the Hero would be doomed to repeat the entire adventure.

Examples of The Hero’s Journey in Action

To better understand this story template beyond the typical sword-and-sorcery genre, let's analyze three examples, from both screenplay and literature, and examine how they implement each of the twelve steps.

The 1976 film Rocky is acclaimed as one of the most iconic sports films because of Stallone’s performance and the heroic journey his character embarks on.

- Ordinary World. Rocky Balboa is a mediocre boxer and loan collector — just doing his best to live day-to-day in a poor part of Philadelphia.

- Call to Adventure. Heavyweight champ Apollo Creed decides to make a big fight interesting by giving a no-name loser a chance to challenge him. That loser: Rocky Balboa.

- Refusal of the Call. Rocky says, “Thanks, but no thanks,” given that he has no trainer and is incredibly out of shape.

- Meeting the Mentor. In steps former boxer Mickey “Mighty Mick” Goldmill, who sees potential in Rocky and starts training him physically and mentally for the fight.

- Crossing the First Threshold. Rocky crosses the threshold of no return when he accepts the fight on live TV, and 一 in parallel 一 when he crosses the threshold into his love interest Adrian’s house and asks her out on a date.

- Tests, Allies, Enemies. Rocky continues to try and win Adrian over and maintains a dubious friendship with her brother, Paulie, who provides him with raw meat to train with.

- Approach to the Inmost Cave. The Inmost Cave in Rocky is Rocky’s own mind. He fears that he’ll never amount to anything — something that he reveals when he butts heads with his trainer, Mickey, in his apartment.

- Ordeal. The start of the training montage marks the beginning of Rocky’s Ordeal. He pushes through it until he glimpses hope ahead while running up the museum steps.

- Reward (Seizing the Sword). Rocky's reward is the restoration of his self-belief, as he recognizes he can try to “go the distance” with Apollo Creed and prove he's more than "just another bum from the neighborhood."

- The Road Back. On New Year's Day, the fight takes place. Rocky capitalizes on Creed's overconfidence to start strong, yet Apollo makes a comeback, resulting in a balanced match.

- Resurrection. The fight inflicts multiple injuries and pushes both men to the brink of exhaustion, with Rocky being knocked down numerous times. But he consistently rises to his feet, enduring through 15 grueling rounds.

- Return with the Elixir. Rocky loses the fight — but it doesn’t matter. He’s won back his confidence and he’s got Adrian, who tells him that she loves him.

Moving outside of the ring, let’s see how this story structure holds on a completely different planet and with a character in complete isolation.

The Martian

In Andy Weir’s bestselling novel (better known for its big screen adaptation) we follow astronaut Mark Watney as he endures the challenges of surviving on Mars and working out a way to get back home.

- The Ordinary World. Botanist Mark and other astronauts are on a mission on Mars to study the planet and gather samples. They live harmoniously in a structure known as "the Hab.”

- Call to Adventure. The mission is scrapped due to a violent dust storm. As they rush to launch, Mark is flung out of sight and the team believes him to be dead. He is, however, very much alive — stranded on Mars with no way of communicating with anyone back home.

- Refusal of the Call. With limited supplies and grim odds of survival, Mark concludes that he will likely perish on the desolate planet.

- Meeting the Mentor. Thanks to his resourcefulness and scientific knowledge he starts to figure out how to survive until the next Mars mission arrives.

- Crossing the First Threshold. Mark crosses the mental threshold of even trying to survive 一 he successfully creates a greenhouse to cultivate a potato crop, creating a food supply that will last long enough.

- Tests, Allies, Enemies. Loneliness and other difficulties test his spirit, pushing him to establish contact with Earth and the people at NASA, who devise a plan to help.

- Approach to the Inmost Cave. Mark faces starvation once again after an explosion destroys his potato crop.

- Ordeal. A NASA rocket destined to deliver supplies to Mark disintegrates after liftoff and all hope seems lost.

- Reward (Seizing the Sword). Mark’s efforts to survive are rewarded with a new possibility to leave the planet. His team 一 now aware that he’s alive 一 defies orders from NASA and heads back to Mars to rescue their comrade.

- The Road Back. Executing the new plan is immensely difficult 一 Mark has to travel far to locate the spaceship for his escape, and almost dies along the way.

- Resurrection. Mark is unable to get close enough to his teammates' ship but finds a way to propel himself in empty space towards them, and gets aboard safely.

- Return with the Elixir. Now a survival instructor for aspiring astronauts, Mark teaches students that space is indifferent and that survival hinges on solving one problem after another, as well as the importance of other people’s help.

Coming back to Earth, let’s now examine a heroine’s journey through the wilderness of the Pacific Crest Trail and her… humanity.

The memoir Wild narrates the three-month-long hiking adventure of Cheryl Strayed across the Pacific coast, as she grapples with her turbulent past and rediscovers her inner strength.

- The Ordinary World. Cheryl shares her strong bond with her mother who was her strength during a tough childhood with an abusive father.

- Call to Adventure. As her mother succumbs to lung cancer, Cheryl faces the heart-wrenching reality to confront life's challenges on her own.

- Refusal of the Call. Cheryl spirals down into a destructive path of substance abuse and infidelity, which leads to hit rock bottom with a divorce and unwanted pregnancy.

- Meeting the Mentor. Her best friend Lisa supports her during her darkest time. One day she notices the Pacific Trail guidebook, which gives her hope to find her way back to her inner strength.

- Crossing the First Threshold. She quits her job, sells her belongings, and visits her mother’s grave before traveling to Mojave, where the trek begins.

- Tests, Allies, Enemies. Cheryl is tested by her heavy bag, blisters, rattlesnakes, and exhaustion, but many strangers help her along the trail with a warm meal or hiking tips.

- Approach to the Inmost Cave. As Cheryl goes through particularly tough and snowy parts of the trail her emotional baggage starts to catch up with her.

- Ordeal. She inadvertently drops one of her shoes off a cliff, and the incident unearths the helplessness she's been evading since her mother's passing.

- Reward (Seizing the Sword). Cheryl soldiers on, trekking an impressive 50 miles in duct-taped sandals before finally securing a new pair of shoes. This small victory amplifies her self-confidence.

- The Road Back. On the last stretch, she battles thirst, sketchy hunters, and a storm, but more importantly, she revisits her most poignant and painful memories.

- Resurrection. Cheryl forgives herself for damaging her marriage and her sense of worth, owning up to her mistakes. A pivotal moment happens at Crater Lake, where she lets go of her frustration at her mother for passing away.

- Return with the Elixir. Cheryl reaches the Bridge of the Gods and completes the trail. She has found her inner strength and determination for life's next steps.

There are countless other stories that could align with this template, but it's not always the perfect fit. So, let's look into when authors should consider it or not.

When should writers use The Hero’s Journey?

The Hero’s Journey is just one way to outline a novel and dissect a plot. For more longstanding theories on the topic, you can go here to read about the ever-popular Three-Act Structure, here to discover Dan Harmon's Story Circle, and here to learn about three more prevalent structures.

So when is it best to use the Hero’s Journey? There are a couple of circumstances which might make this a good choice.

When you need more specific story guidance than simple structures can offer

Simply put, the Hero’s Journey structure is far more detailed and closely defined than other story structure theories. If you want a fairly specific framework for your work than a thee-act structure, the Hero’s Journey can be a great place to start.

Of course, rules are made to be broken . There’s plenty of room to play within the confines of the Hero’s Journey, despite it appearing fairly prescriptive at first glance. Do you want to experiment with an abbreviated “Resurrection” stage, as J.K. Rowling did in Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone? Are you more interested in exploring the journey of an anti-hero? It’s all possible.

Once you understand the basics of this universal story structure, you can use and bend it in ways that disrupt reader expectations.

Need more help developing your book? Try this template on for size:

Get our Book Development Template

Use this template to go from a vague idea to a solid plan for a first draft.

When your focus is on a single protagonist

No matter how sprawling or epic the world you’re writing is, if your story is, at its core, focused on a single character’s journey, then this is a good story structure for you. It’s kind of in the name! If you’re dealing with an entire ensemble, the Hero’s Journey may not give you the scope to explore all of your characters’ plots and subplot — a broader three-act structure may give you more freedom to weave a greater number story threads.

Which story structure is right for you?

Take this quiz and we'll match your story to a structure in minutes!

Whether you're a reader or writer, we hope our guide has helped you understand this universal story arc. Want to know more about story structure? We explain 6 more in our guide — read on!

6 responses

PJ Reece says:

25/07/2018 – 19:41

Nice vid, good intro to story structure. Typically, though, the 'hero's journey' misses the all-important point of the Act II crisis. There, where the hero faces his/her/its existential crisis, they must DIE. The old character is largely destroyed -- which is the absolute pre-condition to 'waking up' to what must be done. It's not more clever thinking; it's not thinking at all. Its SEEING. So many writing texts miss this point. It's tantamount to a religions experience, and nobody grows up without it. STORY STRUCTURE TO DIE FOR examines this dramatic necessity.

↪️ C.T. Cheek replied:

13/11/2019 – 21:01

Okay, but wouldn't the Act II crisis find itself in the Ordeal? The Hero is tested and arguably looses his/her/its past-self for the new one. Typically, the Hero is not fully "reborn" until the Resurrection, in which they defeat the hypothetical dragon and overcome the conflict of the story. It's kind of this process of rebirth beginning in the earlier sections of the Hero's Journey and ending in the Resurrection and affirmed in the Return with the Elixir.

Lexi Mize says:

25/07/2018 – 22:33

Great article. Odd how one can take nearly every story and somewhat plug it into such a pattern.

Bailey Koch says:

11/06/2019 – 02:16

This was totally lit fam!!!!

↪️ Bailey Koch replied:

11/09/2019 – 03:46

where is my dad?

Frank says:

12/04/2020 – 12:40

Great article, thanks! :) But Vogler didn't expand Campbell's theory. Campbell had seventeen stages, not twelve.

Comments are currently closed.

Join a community of over 1 million authors

Reedsy is more than just a blog. Become a member today to discover how we can help you publish a beautiful book.

Meet Reedsy Studio

Plan each story beat with Boards. Plot, write, edit, format — 100% free.

1 million authors trust the professionals on Reedsy. Come meet them.

Enter your email or get started with a social account:

Hero's Journey 101: How to Use the Hero's Journey to Plot Your Story

By Dan Schriever

How many times have you heard this story? A protagonist is suddenly whisked away from their ordinary life and embarks on a grand adventure. Along the way they make new friends, confront perils, and face tests of character. In the end, evil is defeated, and the hero returns home a changed person.

That’s the Hero’s Journey in a nutshell. It probably sounds very familiar—and rightly so: the Hero’s Journey aspires to be the universal story, or monomyth, a narrative pattern deeply ingrained in literature and culture. Whether in books, movies, television, or folklore, chances are you’ve encountered many examples of the Hero’s Journey in the wild.

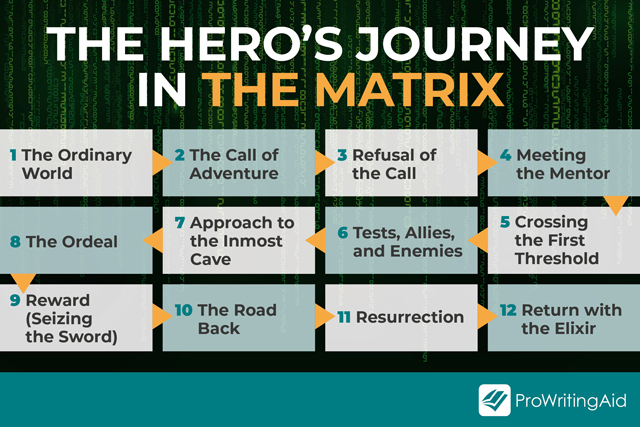

In this post, we’ll walk through the elements of the Hero’s Journey step by step. We’ll also study an archetypal example from the movie The Matrix (1999). Once you have mastered the beats of this narrative template, you’ll be ready to put your very own spin on it.

Sound good? Then let’s cross the threshold and let the journey begin.

What Is the Hero’s Journey?

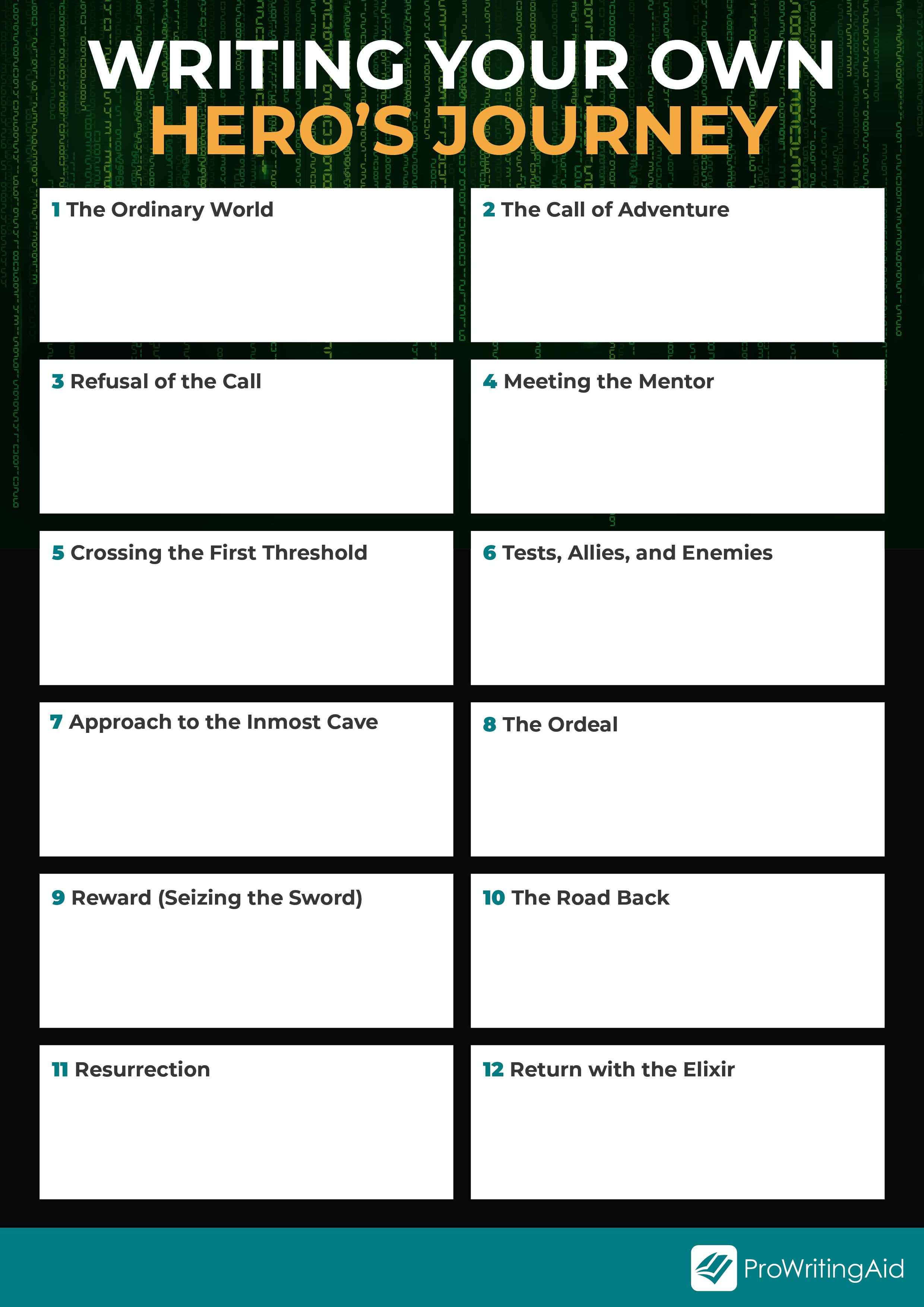

The 12 stages of the hero’s journey, writing your own hero’s journey.

The Hero’s Journey is a common story structure for modeling both plot points and character development. A protagonist embarks on an adventure into the unknown. They learn lessons, overcome adversity, defeat evil, and return home transformed.

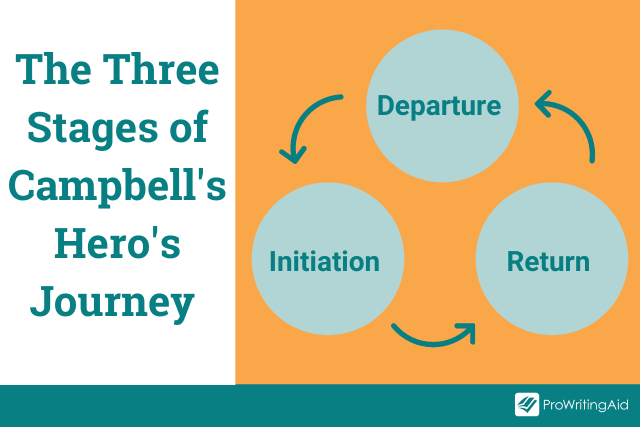

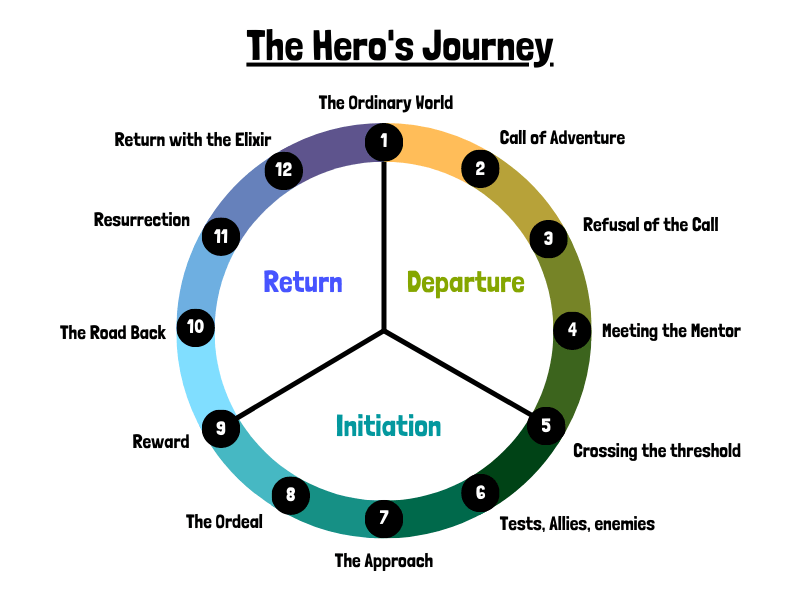

Joseph Campbell , a scholar of literature, popularized the monomyth in his influential work The Hero With a Thousand Faces (1949). Looking for common patterns in mythological narratives, Campbell described a character arc with 17 total stages, overlaid on a more traditional three-act structure. Not all need be present in every myth or in the same order.

The three stages, or acts, of Campbell’s Hero’s Journey are as follows:

1. Departure. The hero leaves the ordinary world behind.

2. Initiation. The hero ventures into the unknown ("the Special World") and overcomes various obstacles and challenges.

3. Return. The hero returns in triumph to the familiar world.

Hollywood has embraced Campbell’s structure, most famously in George Lucas’s Star Wars movies. There are countless examples in books, music, and video games, from fantasy epics and Disney films to sports movies.

In The Writer’s Journey: Mythic Structure for Writers (1992), screenwriter Christopher Vogler adapted Campbell’s three phases into the "12 Stages of the Hero’s Journey." This is the version we’ll analyze in the next section.

For writers, the purpose of the Hero’s Journey is to act as a template and guide. It’s not a rigid formula that your plot must follow beat by beat. Indeed, there are good reasons to deviate—not least of which is that this structure has become so ubiquitous.

Still, it’s helpful to master the rules before deciding when and how to break them. The 12 steps of the Hero's Journey are as follows :

- The Ordinary World

- The Call of Adventure

- Refusal of the Call

- Meeting the Mentor

- Crossing the First Threshold

- Tests, Allies, and Enemies

- Approach to the Inmost Cave

- Reward (Seizing the Sword)

- The Road Back

- Resurrection

- Return with the Elixir

Let’s take a look at each stage in more detail. To show you how the Hero’s Journey works in practice, we’ll also consider an example from the movie The Matrix (1999). After all, what blog has not been improved by a little Keanu Reeves?

#1: The Ordinary World

This is where we meet our hero, although the journey has not yet begun: first, we need to establish the status quo by showing the hero living their ordinary, mundane life.

It’s important to lay the groundwork in this opening stage, before the journey begins. It lets readers identify with the hero as just a regular person, “normal” like the rest of us. Yes, there may be a big problem somewhere out there, but the hero at this stage has very limited awareness of it.

The Ordinary World in The Matrix :

We are introduced to Thomas A. Anderson, aka Neo, programmer by day, hacker by night. While Neo runs a side operation selling illicit software, Thomas Anderson lives the most mundane life imaginable: he works at his cubicle, pays his taxes, and helps the landlady carry out her garbage.

#2: The Call to Adventure

The journey proper begins with a call to adventure—something that disrupts the hero’s ordinary life and confronts them with a problem or challenge they can’t ignore. This can take many different forms.

While readers may already understand the stakes, the hero is realizing them for the first time. They must make a choice: will they shrink from the call, or rise to the challenge?

The Call to Adventure in The Matrix :

A mysterious message arrives in Neo’s computer, warning him that things are not as they seem. He is urged to “follow the white rabbit.” At a nightclub, he meets Trinity, who tells him to seek Morpheus.

#3: Refusal of the Call

Oops! The hero chooses option A and attempts to refuse the call to adventure. This could be for any number of reasons: fear, disbelief, a sense of inadequacy, or plain unwillingness to make the sacrifices that are required.

A little reluctance here is understandable. If you were asked to trade the comforts of home for a life-and-death journey fraught with peril, wouldn’t you give pause?

Refusal of the Call in The Matrix :

Agents arrive at Neo’s office to arrest him. Morpheus urges Neo to escape by climbing out a skyscraper window. “I can’t do this… This is crazy!” Neo protests as he backs off the ledge.

#4: Meeting the Mentor

Okay, so the hero got cold feet. Nothing a little pep talk can’t fix! The mentor figure appears at this point to give the hero some much needed counsel, coaching, and perhaps a kick out the door.

After all, the hero is very inexperienced at this point. They’re going to need help to avoid disaster or, worse, death. The mentor’s role is to overcome the hero’s reluctance and prepare them for what lies ahead.

Meeting the Mentor in The Matrix :

Neo meets with Morpheus, who reveals a terrifying truth: that the ordinary world as we know it is a computer simulation designed to enslave humanity to machines.

#5: Crossing the First Threshold

At this juncture, the hero is ready to leave their ordinary world for the first time. With the mentor’s help, they are committed to the journey and ready to step across the threshold into the special world . This marks the end of the departure act and the beginning of the adventure in earnest.

This may seem inevitable, but for the hero it represents an important choice. Once the threshold is crossed, there’s no going back. Bilbo Baggins put it nicely: “It’s a dangerous business, Frodo, going out your door. You step onto the road, and if you don't keep your feet, there's no knowing where you might be swept off to.”

Crossing the First Threshold in The Matrix :

Neo is offered a stark choice: take the blue pill and return to his ordinary life none the wiser, or take the red pill and “see how deep the rabbit hole goes.” Neo takes the red pill and is extracted from the Matrix, entering the real world .

#6: Tests, Allies, and Enemies

Now we are getting into the meat of the adventure. The hero steps into the special world and must learn the new rules of an unfamiliar setting while navigating trials, tribulations, and tests of will. New characters are often introduced here, and the hero must navigate their relationships with them. Will they be friend, foe, or something in between?

Broadly speaking, this is a time of experimentation and growth. It is also one of the longest stages of the journey, as the hero learns the lay of the land and defines their relationship to other characters.

Wondering how to create captivating characters? Read our guide , which explains how to shape characters that readers will love—or hate.

Tests, Allies, and Enemies in The Matrix :

Neo is introduced to the vagabond crew of the Nebuchadnezzar . Morpheus informs Neo that he is The One , a savior destined to liberate humanity. He learns jiu jitsu and other useful skills.

#7: Approach to the Inmost Cave

Time to get a little metaphorical. The inmost cave isn’t a physical cave, but rather a place of great danger—indeed, the most dangerous place in the special world . It could be a villain’s lair, an impending battle, or even a mental barrier. No spelunking required.

Broadly speaking, the approach is marked by a setback in the quest. It becomes a lesson in persistence, where the hero must reckon with failure, change their mindset, or try new ideas.

Note that the hero hasn’t entered the cave just yet. This stage is about the approach itself, which the hero must navigate to get closer to their ultimate goal. The stakes are rising, and failure is no longer an option.

Approach to the Inmost Cave in The Matrix :

Neo pays a visit to The Oracle. She challenges Neo to “know thyself”—does he believe, deep down, that he is The One ? Or does he fear that he is “just another guy”? She warns him that the fate of humanity hangs in the balance.

#8: The Ordeal

The ordeal marks the hero’s greatest test thus far. This is a dark time for them: indeed, Campbell refers to it as the “belly of the whale.” The hero experiences a major hurdle or obstacle, which causes them to hit rock bottom.

This is a pivotal moment in the story, the main event of the second act. It is time for the hero to come face to face with their greatest fear. It will take all their skills to survive this life-or-death crisis. Should they succeed, they will emerge from the ordeal transformed.

Keep in mind: the story isn’t over yet! Rather, the ordeal is the moment when the protagonist overcomes their weaknesses and truly steps into the title of hero .

The Ordeal in The Matrix :

When Cipher betrays the crew to the agents, Morpheus sacrifices himself to protect Neo. In turn, Neo makes his own choice: to risk his life in a daring rescue attempt.

#9: Reward (Seizing the Sword)

The ordeal was a major level-up moment for the hero. Now that it's been overcome, the hero can reap the reward of success. This reward could be an object, a skill, or knowledge—whatever it is that the hero has been struggling toward. At last, the sword is within their grasp.

From this moment on, the hero is a changed person. They are now equipped for the final conflict, even if they don’t fully realize it yet.

Reward (Seizing the Sword) in The Matrix :

Neo’s reward is helpfully narrated by Morpheus during the rescue effort: “He is beginning to believe.” Neo has gained confidence that he can fight the machines, and he won’t back down from his destiny.

#10: The Road Back

We’re now at the beginning of act three, the return . With the reward in hand, it’s time to exit the inmost cave and head home. But the story isn’t over yet.

In this stage, the hero reckons with the consequences of act two. The ordeal was a success, but things have changed now. Perhaps the dragon, robbed of his treasure, sets off for revenge. Perhaps there are more enemies to fight. Whatever the obstacle, the hero must face them before their journey is complete.

The Road Back in The Matrix :

The rescue of Morpheus has enraged Agent Smith, who intercepts Neo before he can return to the Nebuchadnezzar . The two foes battle in a subway station, where Neo’s skills are pushed to their limit.

#11: Resurrection

Now comes the true climax of the story. This is the hero’s final test, when everything is at stake: the battle for the soul of Gotham, the final chance for evil to triumph. The hero is also at the peak of their powers. A happy ending is within sight, should they succeed.

Vogler calls the resurrection stage the hero’s “final exam.” They must draw on everything they have learned and prove again that they have really internalized the lessons of the ordeal . Near-death escapes are not uncommon here, or even literal deaths and resurrections.

Resurrection in The Matrix :

Despite fighting valiantly, Neo is defeated by Agent Smith and killed. But with Trinity’s help, he is resurrected, activating his full powers as The One . Isn’t it wonderful how literal The Matrix can be?

#12: Return with the Elixir

Hooray! Evil has been defeated and the hero is transformed. It’s time for the protagonist to return home in triumph, and share their hard-won prize with the ordinary world . This prize is the elixir —the object, skill, or insight that was the hero’s true reward for their journey and transformation.

Return with the Elixir in The Matrix :

Neo has defeated the agents and embraced his destiny. He returns to the simulated world of the Matrix, this time armed with god-like powers and a resolve to open humanity’s eyes to the truth.

If you’re writing your own adventure, you may be wondering: should I follow the Hero’s Journey structure?

The good news is, it’s totally up to you. Joseph Campbell conceived of the monomyth as a way to understand universal story structure, but there are many ways to outline a novel. Feel free to play around within its confines, adapt it across different media, and disrupt reader expectations. It’s like Morpheus says: “Some of these rules can be bent. Others can be broken.”

Think of the Hero’s Journey as a tool. If you’re not sure where your story should go next, it can help to refer back to the basics. From there, you’re free to choose your own adventure.

Are you prepared to write your novel? Download this free book now:

The Novel-Writing Training Plan

So you are ready to write your novel. excellent. but are you prepared the last thing you want when you sit down to write your first draft is to lose momentum., this guide helps you work out your narrative arc, plan out your key plot points, flesh out your characters, and begin to build your world..

Be confident about grammar

Check every email, essay, or story for grammar mistakes. Fix them before you press send.

Dan Schriever

Dan holds a PhD from Yale University and CEO of FaithlessMTG

Get started with ProWritingAid

Drop us a line or let's stay in touch via:

- Story Writing Guides

12 Hero’s Journey Stages Explained (+ Free Templates)

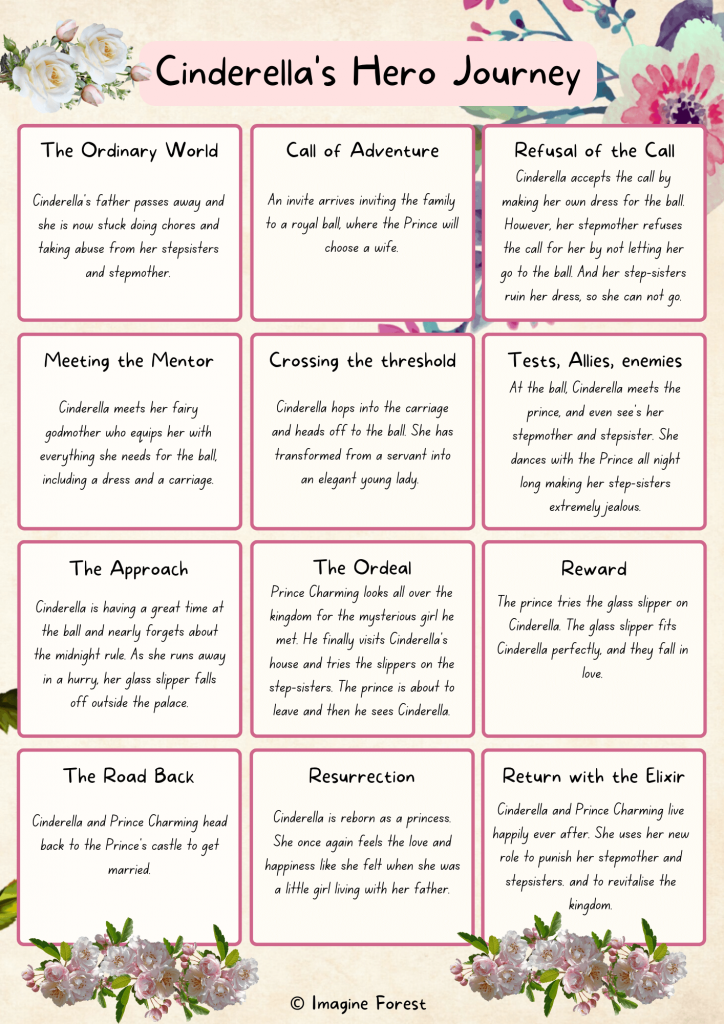

From zero to hero, the hero’s journey is a popular character development arc used in many stories. In today’s post, we will explain the 12 hero’s journey stages, along with the simple example of Cinderella.

The Hero’s Journey was originally formulated by American writer Joseph Campbell to describe the typical character arc of many classic stories, particularly in the context of mythology and folklore. The original hero’s journey contained 17 steps. Although the hero’s journey has been adapted since then for use in modern fiction, the concept is not limited to literature. It can be applied to any story, video game, film or even music that features an archetypal hero who undergoes a transformation. Common examples of the hero’s journey in popular works include Star Wars, Lord of the Rings, The Hunger Games and Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone.

- What is the hero's journey?

Stage 1: The Ordinary World

Stage 2: call of adventure, stage 3: refusal of the call, stage 4: meeting the mentor, stage 5: crossing the threshold, stage 6: tests, allies, enemies, stage 7: the approach, stage 8: the ordeal, stage 9: reward, stage 10: the road back, stage 11: resurrection, stage 12: return with the elixir, cinderella example, campbell’s 17-step journey, leeming’s 8-step journey, cousineau’s 8-step journey.

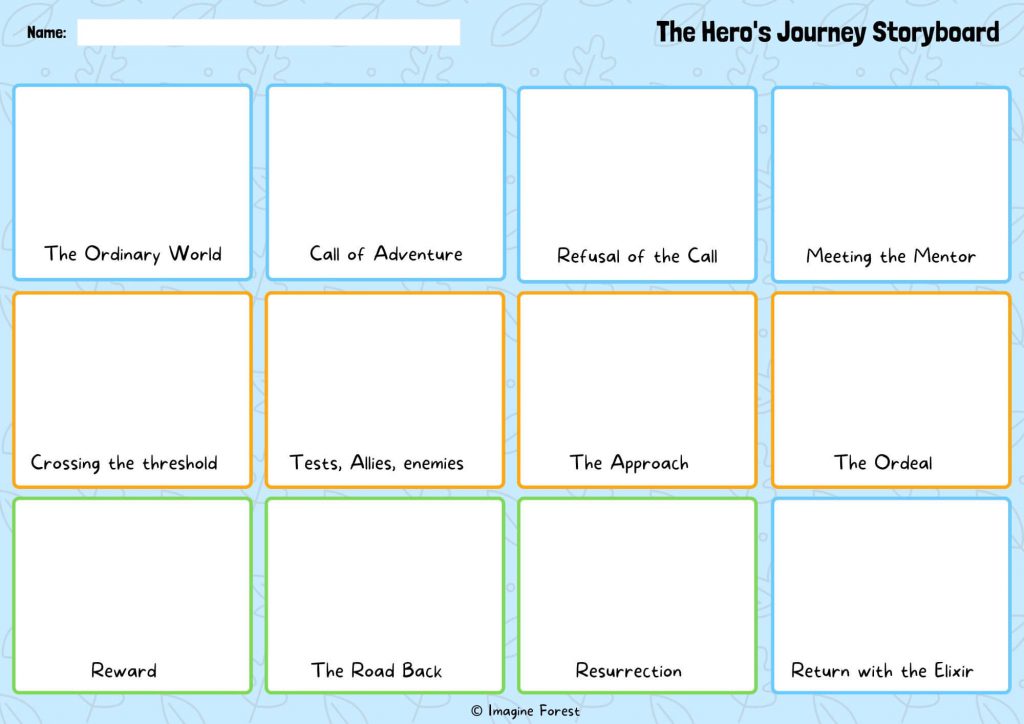

- Free Hero's Journey Templates

What is the hero’s journey?

The hero’s journey, also known as the monomyth, is a character arc used in many stories. The idea behind it is that heroes undergo a journey that leads them to find their true selves. This is often represented in a series of stages. There are typically 12 stages to the hero’s journey. Each stage represents a change in the hero’s mindset or attitude, which is triggered by an external or internal event. These events cause the hero to overcome a challenge, reach a threshold, and then return to a normal life.

The hero’s journey is a powerful tool for understanding your characters. It can help you decide who they are, what they want, where they came from, and how they will change over time. It can be used to

- Understand the challenges your characters will face

- Understand how your characters react to those challenges

- Help develop your characters’ traits and relationships

In this post, we will explain each stage of the hero’s journey, using the example of Cinderella.

You might also be interested in our post on the story mountain or this guide on how to outline a book .

12 Hero’s Journey Stages

The archetypal hero’s journey contains 12 stages and was created by Christopher Vogler. These steps take your main character through an epic struggle that leads to their ultimate triumph or demise. While these steps may seem formulaic at first glance, they actually form a very flexible structure. The hero’s journey is about transformation, not perfection.

Your hero starts out in the ordinary world. He or she is just like every other person in their environment, doing things that are normal for them and experiencing the same struggles and challenges as everyone else. In the ordinary world, the hero feels stuck and confused, so he or she goes on a quest to find a way out of this predicament.

Example: Cinderella’s father passes away and she is now stuck doing chores and taking abuse from her stepsisters and stepmother.

The hero gets his or her first taste of adventure when the call comes. This could be in the form of an encounter with a stranger or someone they know who encourages them to take a leap of faith. This encounter is typically an accident, a series of coincidences that put the hero in the right place at the right time.

Example: An invite arrives inviting the family to a royal ball where the Prince will choose a wife.

Some people will refuse to leave their safe surroundings and live by their own rules. The hero has to overcome the negative influences in order to hear the call again. They also have to deal with any personal doubts that arise from thinking too much about the potential dangers involved in the quest. It is common for the hero to deny their own abilities in this stage and to lack confidence in themselves.

Example: Cinderella accepts the call by making her own dress for the ball. However, her stepmother refuses the call for her by not letting her go to the ball. And her step-sisters ruin her dress, so she can not go.

After hearing the call, the hero begins a relationship with a mentor who helps them learn about themselves and the world. In some cases, the mentor may be someone the hero already knows. The mentor is usually someone who is well-versed in the knowledge that the hero needs to acquire, but who does not judge the hero for their lack of experience.

Example: Cinderella meets her fairy godmother who equips her with everything she needs for the ball, including a dress and a carriage.

The hero leaves their old life behind and enters the unfamiliar new world. The crossing of the threshold symbolises leaving their old self behind and becoming a new person. Sometimes this can include learning a new skill or changing their physical appearance. It can also include a time of wandering, which is an essential part of the hero’s journey.

Example: Cinderella hops into the carriage and heads off to the ball. She has transformed from a servant into an elegant young lady.

As the hero goes on this journey, they will meet both allies (people who help the hero) and enemies (people who try to stop the hero). There will also be tests, where the hero is tempted to quit, turn back, or become discouraged. The hero must be persistent and resilient to overcome challenges.

Example: At the ball, Cinderella meets the prince, and even see’s her stepmother and stepsister. She dances with Prince all night long making her step-sisters extremely jealous.

The hero now reaches the destination of their journey, in some cases, this is a literal location, such as a cave or castle. It could also be metaphorical, such as the hero having an internal conflict or having to make a difficult decision. In either case, the hero has to confront their deepest fears in this stage with bravery. In some ways, this stage can mark the end of the hero’s journey because the hero must now face their darkest fears and bring them under control. If they do not do this, the hero could be defeated in the final battle and will fail the story.

Example: Cinderella is having a great time at the ball and nearly forgets about the midnight rule. As she runs away in a hurry, her glass slipper falls off outside the palace.

The hero has made it to the final challenge of their journey and now must face all odds and defeat their greatest adversary. Consider this the climax of the story. This could be in the form of a physical battle, a moral dilemma or even an emotional challenge. The hero will look to their allies or mentor for further support and guidance in this ordeal. Whatever happens in this stage could change the rest of the story, either for good or bad.

Example: Prince Charming looks all over the kingdom for the mysterious girl he met at the ball. He finally visits Cinderella’s house and tries the slippers on the step-sisters. The prince is about to leave and then he sees Cinderella in the corner cleaning.

When the hero has defeated the most powerful and dangerous of adversaries, they will receive their reward. This reward could be an object, a new relationship or even a new piece of knowledge. The reward, which typically comes as a result of the hero’s perseverance and hard work, signifies the end of their journey. Given that the hero has accomplished their goal and served their purpose, it is a time of great success and accomplishment.

Example: The prince tries the glass slipper on Cinderella. The glass slipper fits Cinderella perfectly, and they fall in love.

The journey is now complete, and the hero is now heading back home. As the hero considers their journey and reflects on the lessons they learned along the way, the road back is sometimes marked by a sense of nostalgia or even regret. As they must find their way back to the normal world and reintegrate into their former life, the hero may encounter additional difficulties or tests along the way. It is common for the hero to run into previous adversaries or challenges they believed they had overcome.

Example: Cinderella and Prince Charming head back to the Prince’s castle to get married.

The hero has one final battle to face. At this stage, the hero might have to fight to the death against a much more powerful foe. The hero might even be confronted with their own mortality or their greatest fear. This is usually when the hero’s true personality emerges. This stage is normally symbolised by the hero rising from the dark place and fighting back. This dark place could again be a physical location, such as the underground or a dark cave. It might even be a dark, mental state, such as depression. As the hero rises again, they might change physically or even experience an emotional transformation.

Example: Cinderella is reborn as a princess. She once again feels the love and happiness that she felt when she was a little girl living with her father.

At the end of the story, the hero returns to the ordinary world and shares the knowledge gained in their journey with their fellow man. This can be done by imparting some form of wisdom, an object of great value or by bringing about a social revolution. In all cases, the hero returns changed and often wiser.

Example: Cinderella and Prince Charming live happily ever after. She uses her new role to punish her stepmother and stepsisters and to revitalise the kingdom.

We have used the example of Cinderella in Vogler’s hero’s journey model below:

Below we have briefly explained the other variations of the hero’s journey arc.

The very first hero’s journey arc was created by Joseph Campbell in 1949. It contained the following 17 steps:

- The Call to Adventure: The hero receives a call or a reason to go on a journey.

- Refusal of the Call: The hero does not accept the quest. They worry about their own abilities or fear the journey itself.

- Supernatural Aid: Someone (the mentor) comes to help the hero and they have supernatural powers, which are usually magical.

- The Crossing of the First Threshold: A symbolic boundary is crossed by the hero, often after a test.

- Belly of the Whale: The point where the hero has the most difficulty making it through.

- The Road of Trials: In this step, the hero will be tempted and tested by the outside world, with a number of negative experiences.

- The Meeting with the Goddess: The hero meets someone who can give them the knowledge, power or even items for the journey ahead.

- Woman as the Temptress: The hero is tempted to go back home or return to their old ways.

- Atonement with the Father: The hero has to make amends for any wrongdoings they may have done in the past. They need to confront whatever holds them back.

- Apotheosis: The hero gains some powerful knowledge or grows to a higher level.

- The Ultimate Boon: The ultimate boon is the reward for completing all the trials of the quest. The hero achieves their ultimate goal and feels powerful.

- Refusal of the Return: After collecting their reward, the hero refuses to return to normal life. They want to continue living like gods.

- The Magic Flight: The hero escapes with the reward in hand.

- Rescue from Without: The hero has been hurt and needs help from their allies or guides.

- The Crossing of the Return Threshold: The hero must come back and learn to integrate with the ordinary world once again.

- Master of the Two Worlds: The hero shares their wisdom or gifts with the ordinary world. Learning to live in both worlds.

- Freedom to Live: The hero accepts the new version of themselves and lives happily without fear.

David Adams Leeming later adapted the hero’s journey based on his research of legendary heroes found in mythology. He noted the following steps as a pattern that all heroes in stories follow:

- Miraculous conception and birth: This is the first trauma that the hero has to deal with. The Hero is often an orphan or abandoned child and therefore faces many hardships early on in life.

- Initiation of the hero-child: The child faces their first major challenge. At this point, the challenge is normally won with assistance from someone else.

- Withdrawal from family or community: The hero runs away and is tempted by negative forces.

- Trial and quest: A quest finds the hero giving them an opportunity to prove themselves.

- Death: The hero fails and is left near death or actually does die.

- Descent into the underworld: The hero rises again from death or their near-death experience.

- Resurrection and rebirth: The hero learns from the errors of their way and is reborn into a better, wiser being.

- Ascension, apotheosis, and atonement: The hero gains some powerful knowledge or grows to a higher level (sometimes a god-like level).

In 1990, Phil Cousineau further adapted the hero’s journey by simplifying the steps from Campbell’s model and rearranging them slightly to suit his own findings of heroes in literature. Again Cousineau’s hero’s journey included 8 steps:

- The call to adventure: The hero must have a reason to go on an adventure.

- The road of trials: The hero undergoes a number of tests that help them to transform.

- The vision quest: Through the quest, the hero learns the errors of their ways and has a realisation of something.

- The meeting with the goddess: To help the hero someone helps them by giving them some knowledge, power or even items for the journey ahead.

- The boon: This is the reward for completing the journey.

- The magic flight: The hero must escape, as the reward is attached to something terrible.

- The return threshold: The hero must learn to live back in the ordinary world.

- The master of two worlds: The hero shares their knowledge with the ordinary world and learns to live in both worlds.

As you can see, every version of the hero’s journey is about the main character showing great levels of transformation. Their journey may start and end at the same location, but they have personally evolved as a character in your story. Once a weakling, they now possess the knowledge and skill set to protect their world if needed.

Free Hero’s Journey Templates

Use the free Hero’s journey templates below to practice the skills you learned in this guide! You can either draw or write notes in each of the scene boxes. Once the template is complete, you will have a better idea of how your main character or the hero of your story develops over time:

The storyboard template below is a great way to develop your main character and organise your story:

Did you find this guide on the hero’s journey stages useful? Let us know in the comments below.

Marty the wizard is the master of Imagine Forest. When he's not reading a ton of books or writing some of his own tales, he loves to be surrounded by the magical creatures that live in Imagine Forest. While living in his tree house he has devoted his time to helping children around the world with their writing skills and creativity.

Related Posts

Comments loading...

All Subjects

study guides for every class

That actually explain what's on your next test, the hero's journey, from class:, intro to contemporary literature.

The hero's journey is a narrative structure that outlines the typical adventure of the protagonist, often involving stages like departure, initiation, and return. This framework highlights not just the external challenges faced by the hero but also their internal transformation, as they grow and learn valuable lessons throughout their journey. It's a pattern that appears in various genres, showcasing both personal and societal themes that resonate with audiences.

congrats on reading the definition of the hero's journey . now let's actually learn it.

5 Must Know Facts For Your Next Test

- The hero's journey often begins with a 'call to adventure,' prompting the hero to leave their ordinary world for new challenges.

- Key stages of the hero's journey include facing trials, receiving assistance from allies, and ultimately achieving a significant goal or insight.

- The return stage usually sees the hero returning home with newfound knowledge or gifts that can benefit their community.

- The structure emphasizes both external adventures and internal growth, illustrating how challenges can lead to self-discovery.

- Many popular works in science fiction and literature employ this framework to depict characters' journeys through unfamiliar settings or personal conflicts.

Review Questions

- The hero's journey framework enhances storytelling by providing a relatable structure that resonates with audiences. It captures the essential human experience of facing challenges and overcoming them, which allows readers and viewers to connect deeply with the characters. This narrative arc creates anticipation as we witness the hero's transformation through trials and adventures, making the story more engaging and impactful.

- Themes of self-discovery are central to the hero's journey as protagonists often confront their limitations and insecurities while navigating challenges. For example, in contemporary works like 'The Hunger Games,' Katniss Everdeen evolves from a survival-focused individual to a leader who embodies resilience and hope. This journey highlights her internal struggles as she learns about her values and identity amidst external conflicts, demonstrating how personal growth is integral to her narrative.

- External challenges are crucial in shaping a hero's identity because they force characters out of their comfort zones and into situations that require them to confront their fears and weaknesses. By facing these obstacles, heroes like Frodo Baggins in 'The Lord of the Rings' not only develop courage but also gain insights about friendship, sacrifice, and responsibility. The interplay between these challenges and personal growth illustrates how heroes evolve through adversity, leading to profound changes in who they are at their core.

Related terms

Monomyth : Another name for the hero's journey, emphasizing the universal nature of the narrative across different cultures and myths.

Transformation : The process of change that the hero undergoes throughout their journey, which often leads to personal growth and self-discovery.

Mentor : A character who provides guidance and support to the hero, often helping them navigate challenges on their journey.

" The hero's journey " also found in:

Subjects ( 28 ).

- Advanced Film Writing

- Advanced Media Writing

- American Cinema to 1960

- Art and Literature

- Art and Technology

- Business Storytelling

- Design Thinking for Business

- Epic and Saga

- Foundations of Data Science

- Greek Tragedy

- Greek and Roman Myths

- Improvisational Leadership

- Intermediate Cinematography

- Introduction to Comparative Literature: Literary and Cultural History

- Introduction to Old English

- Literary Theory and Criticism

- Literature in English: Late-17th to Mid-19th Century

- Myth and Literature

- Religion and Literature

- Rescuing Lost Stories

- Screenwriting I

- Storytelling for Film and Television

- Strategic Brand Storytelling

- The Craft of Writing: Film Focus

- World Literature I

- World Literature II

- Writing for Public Relations

- Writing the Television Pilot

© 2024 Fiveable Inc. All rights reserved.

Ap® and sat® are trademarks registered by the college board, which is not affiliated with, and does not endorse this website..

A Practical Guide to Joseph Campbell and the Hero’s Journey

OVERVIEW: What are the hero’s journey steps? That is, what’s the psychological process we go through that can lead to inner transformation? This guide answers these questions.

______________

Treasure, love, reward, approval, honor, status, freedom, and survival … these are some of the many things associated with the hero’s journey.

However, we don’t find the meaning of the hero’s journey in slaying the dragon or saving the princess.

These are but colorful metaphors and symbols for a more significant purpose.

Battling inner and outer demons, confronting bullies, and courting your ideal mate symbolize a passage through the often treacherous path of self-discovery toward adulthood.

If you complete one of these “adventures,” you’re different. Sometimes visually, but always internally.

Here, we’ll explore the meaning of the hero’s journey steps and see how it applies to psychological development and our ability to actualize our potential.

Let’s dive in …

What is the Hero’s Journey?

The hero’s journey refers to a common motif, or set of patterns, found in many ancient mythologies around the world.

The hero’s journey steps are said to be universal and found throughout recorded history.

The popularization of the hero’s journey is attributed to the late mythologist Joseph Campbell.

These stages lead an individual (the would-be hero) through a challenging process of change that often includes great hardships.

This well-known story structure is used in many modern films and storytelling. However, the true meaning of the hero’s journey motif is psychological in origin.

What is the Monomyth?

Joseph Campbell was a curious mythologist. In the field of comparative mythology, most scholars examine how one culture’s myths are different than another.

Instead of focusing on the many differences between cultural myths and religious stories, however, Campbell did the opposite: He looked for the similarities.

His studies resulted in what’s called the monomyth . The monomyth is a universal story structure.

Essentially, it’s a story template that takes a character through a sequence of stages. Campbell began identifying the patterns of this monomyth (the hero’s journey steps).

Over and over again, he was amazed to find this structure in the cultures he studied. He also observed the same sequence in many religions including the stories of Gautama Buddha, Moses, and Jesus Christ.

Campbell outlined the stages of the monomyth in his classic book The Hero with a Thousand Faces (1949).

What is the Hero?

The main character in the monomyth is the hero .

The hero isn’t a person, but an archetype —a set of universal images combined with specific patterns of behavior.

Think of a protagonist from your favorite film. He or she represents the hero.

The storyline of the film enacts the hero’s journey.

The Hero archetype resides in the psyche of every individual, which is one of the primary reasons we love hearing and watching stories.

What is a Myth?

We might ask, why explore the hero’s journey steps?

Sure, Hollywood uses it as their dominant story structure for its films (more on that later). But what relevance does it have for us as individuals?

Today, when we speak of “myth,” we refer to something that’s commonly believed, but untrue.

Myth, for minds like Campbell and Carl Jung however, had a much deeper meaning. Myths, for them, represent dreams of the collective psyche .

That is, in understanding the symbolic meaning of a myth, you come to know the psychological undercurrent—including hidden motivations , tensions, and desires—of the people and culture.

What is the Power of Myth?

Campbell explains to Bill Moyer in The Power of Myth : 1 Joseph Campbell, The Power of Myth , 1991, 193.

Mythology is not a lie, mythology is poetry, it is metaphorical. It has been well said that mythology is the penultimate truth–penultimate because the ultimate cannot be put into words. It is beyond words. Beyond images, beyond that bounding rim of the Buddhist Wheel of Becoming. Mythology pitches the mind beyond that rim, to what can be known but not told.

As Campbell eloquently puts it in The Hero with a Thousand Faces ,

Mythology is psychology misread as biography, history, and cosmology.

Because the hero’s journey steps represent a monomyth that we can observe in most, if not all, cultures, it represents a process that is relevant to the entire human family .

What is this Process Within the Hero’s Journey?

It’s the process of personal transformation from an innocent child into a mature adult.

The child is born into a set of rules and beliefs of a group of people.

Through the child’s heroic efforts, he must break free from these conventions (transcend them) to discover himself.

In the process, the individual returns to his soul.

If we think of the hero’s journey as a roadmap for self-development, it can hold a lot of value for us.

A Quick Note About Gender: Masculine vs Feminine

This psychological decoding is based on a “Jungian” understanding of the psyche.

The hero is ultimately a masculine archetype. The female counterpart would be the heroine. While the hero and the heroine certainly share many attributes, they are not the same.

Similarly, the hero’s journey is predominantly a process of development for the masculine psyche. The hero archetype is associated with autonomy, building structure, and learning about limitations, which are qualities associated with masculine energy.

However, note that “masculine” and “feminine” are not the same as “man” and “woman.” The psyche of a man has a feminine counterpart—what Jung called the anima . The psyche of a woman has a masculine archetype called the animus . For this reason, the hero’s journey does have universal relevance.

While Western culture seems riddled with gender confusion, there are distinct differences between the feminine and masculine psyche .

Okay, now back to our story …

The 3 Main Stages of the Hero’s Journey

Okay, so now let’s begin to break down the structure and sequence of the hero’s journey.

As Campbell explains:

The usual hero adventure begins with someone from whom something has been taken, or who feels there is something lacking in the normal experience available or permitted to the members of society. The person then takes off on a series of adventures beyond the ordinary, either to recover what has been lost or to discover some life-giving elixir. It’s usually a cycle, a coming and a returning.

This cycle of coming and returning has 3 clear stages:

Stage 1: Departure

Campbell called the initial stage departure or the call to adventure . The hero departs from the world he knows.

Luke Skywalker leaves his home planet to join Obi-Wan to save the princess. Neo gets unplugged from The Matrix with the help of Morpheus and his crew.

In the Departure stage, you leave the safety of the world you know and enter the unknown.

Campbell writes of this stage in The Hero with a Thousand Faces :

This first step of the mythological journey—which we have designated the “call to adventure”—signifies that destiny has summoned the hero and transferred his spiritual center of gravity from within the pale of his society to a zone unknown.

That is, the hero must leave the known “conventional world” and enter a “special world” that is foreign.

Stage 2: Initiation

Now the hero must face a series of trials and tribulations. The hero’s journey isn’t safe.

The hero is tested in battle, skill, and conflict. He may not succeed in each action but must press on.

The protagonist will meet allies, enemies, and mentors with supernatural aid throughout the initiation stage.

Stage 3: Return

Having endured the trials and hardships of the adventure, the hero returns home.

But the hero is no longer the same. An internal transformation has taken place through the maturation process of the experience.

Luke is now a Jedi and has come to peace with his past. Neo embraces his destiny and liberates himself from the conventions of The Matrix.

The Hero’s Journey in Drama

In Three Uses of a Knife , famed playwright David Mamet suggests a similar three-act structure for plays and dramas: 2 David Mamet, Three Uses of the Knife: On the Nature and Purpose of Drama , 2000.

Act 1: Thesis . The drama presents life as it is for the protagonist. The ordinary world.

Act 2: Antithesis . The protagonist faces opposing forces that send him into an upheaval (disharmony).

Act 3: Synthesis . The protagonist attempts to integrate the old life with the new one.

We note that problems, challenges, and upheavals are the defining characteristic of this journey.

Without problems, the path toward growth is usually left behind. (More on this topic below.)

Assessing Your Place in the Hero’s Journey

Before we explore the stages of the monomyth more closely, let’s look at what these three phases reveal about self-mastery and psychological development.

Stage 1 represents our comfort zone. We feel safe here because it is known to us.

Stages 2 and 3, however, represent the unknown . Embracing the unknown means letting go of safety.

Abraham Maslow points out that we are confronted with an ongoing series of choices throughout life between safety and growth, dependence and independence, regression and progression, immaturity and maturity.

Maslow writes in Toward a Psychology of Being : 3 Abraham Maslow, Toward a Psychology of Being , 2014.

We grow forward when the delights of growth and anxieties of safety are greater than the anxieties of growth and the delights of safety.

Is it now clear why so many of us refuse the call to adventure?

We cling to the safety of the known instead of embracing the “delight of growth” that only comes from the unknown.

Campbell’s 17 Stages of the Hero’s Journey

Joseph Campbell didn’t just outline three stages of the monomyth. In The Hero with a Thousand Faces , he deconstructs every step along the journey.

The stages of the hero’s journey are the common sequence of events that occurred in the monomyth motif.

Technically speaking, Campbell outlined 17 stages in his The Hero with a Thousand Faces:

- 1: The Call to Adventure

- 2: Refusal of the Call

- 3: Supernatural Aid

- 4: The Crossing of the First Threshold

- 5: Belly of the Whale

- 6: The Road of Trials

- 7: The Meeting with the Goddess

- 8: Woman as the Temptress

- 9: Atonement with the Father

- 10: Apotheosis

- 11: The Ultimate Boon

- 12: Refusal of the Return

- 13: The Magic Flight

- 14: Rescue from Without

- 15: The Crossing of the Return Threshold

- 16: Master of the Two Worlds

- 17: Freedom to Live

These 17 stages or hero’s journey steps can be found globally in the myths and legends throughout recorded history.

The Modified 12 Hero’s Journey Steps

Now, let’s review these stages of the hero’s journey in more detail.

I’m going to outline these steps below using a slightly simplified version from Christopher Vogler’s The Writer’s Journey: Mythic Structure for Writers .

Vogler’s model, which is used throughout Hollywood, only has 12 steps (compared to 17), and I think it does a solid job of keeping the essence of Campbell’s monomyth structure intact.

As you read these hero’s journey steps, see if you can determine how they apply to your development.

Step 1: The Ordinary World

Before a would-be hero can enter the special world, he must first live in the ordinary world.

The ordinary world is different for each of us—it represents our norms, customs, conditioned beliefs, and behaviors. The ordinary world is sometimes referred to as the “conventional world.”

In The Hobbit , the ordinary world is the Shire where Bilbo Baggins lives with all the other Hobbits—gardening, eating and celebrating—living a simple life.

Novelist J.R.R. Tolkien contrasts this life in the Shire with the special world of wizards, warriors, men, elves, dwarfs, and evil forces on the brink of world war.

Step 2: The Call to Adventure

The first hero’s journey step is the call to adventure.

The call to adventure marks a transition from the ordinary world to the special world. The hero is introduced to his quest of great consequence.

Obi-Wan said to Luke, “You must come with me to Alderaan.” That is, Luke is invited to leave the ordinary world of his aunt and uncle’s farm life and go on an adventure with a Jedi knight.

Joseph Campbell explains: 4 Joseph Campbell, The Hero’s Journey: Joseph Campbell On His Life And Work , 1990.

The call to adventure signifies that destiny has summoned the hero and transferred his spiritual center of gravity from within the pale of this society to a zone unknown.

Step 3: Refusal of the Call

Fear of change as well as death, however, often leads the hero to refuse the call to adventure .

The ordinary world represents our comfort zone; the special world signifies the unknown.

Luke Skywalker immediately responds to Obi-Wan, “I can’t go with you,” citing his chores and responsibilities at home.

Step 4: Meeting the Mentor

Campbell called this archetype the “mentor with supernatural aid.”

Generally, at an early stage of the adventure, the hero is graced by the presence of a wise sage . Personified in stories as a magical counselor , a reclusive hermit, or a wise leader, the mentor’s role is to help guide the hero.

Think Obi-Wan, Yoda, Gandalf, Morpheus, or Dumbledore. Sometimes cloaked in mystery and secret language, a mentor manifests when the hero is ready.

Sadly, our modern world is depleted of wise elders or shamans who can effectively bless the younger generation. (A topic for a different day.) For most of us, it is best to seek wise counsel from your inner guide , the Self within.

Step 5: Cross the First Threshold

The hero resists change initially but is ultimately forced to make a critical decision: embark on the adventure or forever remain in the ordinary world with its illusion of security.

Although Luke refuses the call to adventure initially, when he returns home to see his aunt and uncle dead, he immediately agrees to go with Obi-Wan. He crossed the first threshold.

In one sense, the first threshold is the point of no return. Once the hero shoots across the unstable suspension bridge, it bursts into flames.

There’s no turning back, at least, not how he came.

The first threshold can mark a major decision in our personal lives:

- “I’m going to travel around the globe.”

- “I’m going to transform my physical health.”

- “I am going to write a book.”

- “I’m going to master the flute.”

- “I’m going to realize my true nature.”

This first breakthrough is a feat within itself; however, it is only the first of many turning points.

Step 6: Tests, Allies, Enemies

Along the hero’s journey, the main character encounters many obstacles and allies.

Luke meets Obiwan (mentor), Han Solo, Princess Leia, and the rebel alliance while fighting many foes. Neo meets Morpheus (mentor), Trinity, and the rest of the Nebuchadnezzar crew while having to fight Agents in a strange world.

Some people may try to stop you along your quest—possibly saying you’re unreasonable or unrealistic. These “dream-stoppers” are often cleverly masked as friends and family who appear to have positive intentions but hinder your development nonetheless.

Your ability to identify obstructions on your path and align with support along your adventure is critical to your adventure.

Unfortunately, because few complete their hero’s journey to mature adulthood, most people will unconsciously attempt to sabotage yours.

Step 7: Approach to the Inmost Cave

The next significant threshold is often more treacherous than the first.

Entering the villain’s castle or the evil billionaire’s mansion, this second major decision usually puts the hero at significant physical and psychological risks.

Neo decides to go save Morpheus who’s being held in a building filled with Agents.

Within the walls of the innermost cave lies the cornerstone of the special world where the hero closes in on his objective.

For a man, the innermost cave represents the Mother Complex, a regressive part of him that seeks to return to the safety of the mother. 5 Robert Johnson, He: Understanding Masculine Psychology, 1989. When a man seeks safety and comfort—when he demands pampering—it means he’s engulfed within the innermost cave.

For a woman, the innermost cave often represents learning how to surrender to the healing power of nurturance—to heal the handless maiden. 6 Robert Johnson, The Fisher King and the Handless Maiden: Understanding the Wounded Feeling Function in Masculine and Feminine Psychology , 1995.

Step 8: Ordeal

No worthwhile adventure is easy. There are many perils on the path to growth, self-discovery , and self-realization.

A major obstacle confronts the hero, and the future begins to look dim: a trap, a mental imprisonment, or imminent defeat on the battlefield.

It seems like the adventure will come to a sad conclusion, as all hope appears lost. But hope remains and it is in these moments of despair when the hero must access a hidden part of himself—one more micron of energy, strength, faith, or creativity to find his way out of the belly of the beast.

Neo confronts Agent Smith in the subway station—something that was never done before. The hero must call on an inner power he doesn’t know he possesses.

Step 9: Reward

Having defeated the enemy and slain the dragon, the hero receives the prize. Pulling the metaphorical sword from the stone, the hero achieves the objective he set out to complete.

Whether the reward is monetary, physical, romantic, or spiritual, the hero transforms. Usually, the initial prize sought by the hero is physical—the sword in the stone or a physical treasure of some kind.

Step 10: The Road Back

Alas, the adventure isn’t over yet. There usually needs to be one last push to return home. Now the hero must return to the world from which he came with the sacred elixir.

Challenges still lie ahead in the form of villains, roadblocks, and inner demons. The hero must deal with whatever issues were left unresolved at this stage of the journey.

Taking moral inventory, examining the Shadow , and performing constant self-inquiry help the hero identify weaknesses and blindspots that will later play against him.

Step 11: Resurrection

Before returning home—before the adventure is over—there’s often one more unsuspected, unforeseen ordeal.

This final threshold, which may be more difficult than the prior moment of despair, provides one last test to solidify the growth of the hero. This threshold represents the final climax.

Neo is shot and killed by Agent Smith. And, he literally resurrects to confront the enemy one last time following his transformation.

The uncertain Luke Skywalker takes that “one in a million” shot from his X-Wing to destroy the Death Star.

Step 12: Return with the Elixir

Often, the prize the hero initially sought (in Step 9) becomes secondary as a result of the personal transformation he undergoes.