Thomas Cole, The Voyage of Life

Cole’s extraordinary series chronicles each stage of human life: childhood, youth, manhood, and old age.

Thomas Cole, The Voyage of Life ( Childhood , Youth , Manhood , Old Age ), 1842, oil on canvas, Childhood 134.3 x 195.3 cm; Youth 134.3 x 194.9 cm; Manhood 134.3 x 202.6 cm; Old Age 133.4 x 196.2 cm, original commission by Samuel Ward dates to 1839–40; those canvases are now in the Munson-Williams-Proctor-Arts-Institute in Utica, NY; the set at the National Gallery of Art is a copy made by the artist in Europe after tracings of the original so that Cole could publicly display the paintings and sell engravings from the set (National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.). Speakers: Dr. Bryan Zygmont and Dr. Steven Zucker

Bibliography

Childhood , Youth , Manhood , and Old Age at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Thomas Cole on the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

William H. Truettner and Alan Wallach, editors, Thomas Cole: Landscape into History , exhibition catalogue (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1994).

Images for teaching and learning

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:.

[flickr_tags user_id=”82032880@N00″ tags=”thevoyageoflife,”]

More Smarthistory images…

Cite this page

Your donations help make art history free and accessible to everyone!

The Voyage of Life: Childhood

The Voyage of Life: Childhood is a Romantic Oil on Canvas Painting created by Thomas Cole in 1842 . It lives at the National Gallery of Art, Washington in the United States . The image is in the Public Domain , and tagged Water , Boats and The Sublime . Download See The Voyage of Life: Childhood in the Kaleidoscope

Notch of the White Mountains (Crawford Notch)

The Course of Empire 5: Desolation

The Voyage of Life: Manhood

Snow Storm: Steam-Boat off a Harbour's Mouth

Rain, Steam, and Speed - The Great Western Railway

Supper at Emmaus (1606)

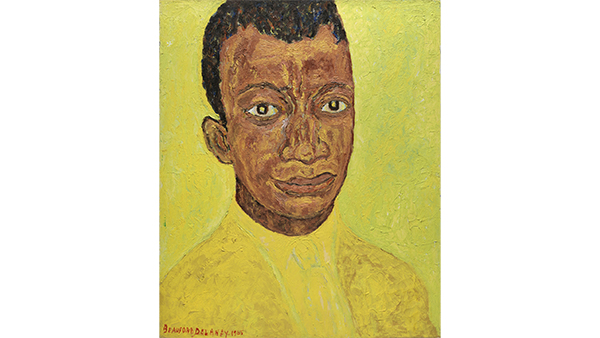

Portrait of Merce Cunningham

A Gathering (Tertulia)

Arrangement of Specimens

Self Portrait with Black Dog

By continuing to browse Obelisk you agree to our Cookie Policy

323 E. Freemason St. Open Saturday and Sunday Noon–5 p.m.

Reading Room Wednesday-Friday 10 a.m.–5 p.m. Closed May 17-19, 2024

The oldest Jewish home in America open to the public as a museum offers a glimpse of the life of an early 19th century merchant family. More about the house

With an extensive collection of more than 106,000 rare and unique volumes relating to the history of art, the Jean Outland Chrysler Art Library is one of the most significant art libraries in the South. More about the library

One Memorial Place, Norfolk, VA Get Directions

Visit our Museum Shop and Zinnia Cafe .

A state-of-art facility on the Museum’s campus. See a free glassmaking demo Tuesdays–Sunday at noon. Like what you see? Take a class with us! More about the Studio

The home of the first permanent Jewish residents of Norfolk, this historic house offers a glimpse of the life of a wealthy early 19th-century merchant family. More about the house

With an extensive collection of more than 106,000 rare and unique volumes relating to the history of art, the Jean Outland Chrysler Library is one of the most significant art libraries in the South. More about the Library

The perfect place for your big day or special event. Get the details

Field trips are available for groups of 60 or fewer. More about field trips

Visit one of the most significant art libraries in the South. More about the library

Our story spans well over 100 years. See where we began, how we grew, and where we're going. Explore our history

See what's happening at the Museum, read Chrysler Magazine, and find our Media Center. Read now

One Memorial Place Norfolk, VA 23510

245 Grace Street Norfolk, VA 23510 757-333-6299

Get Directions

Bringing the world’s top glass art talent to Hampton Roads Find out more

Meet the brilliant minds behind the Studio. See the team

Share everything you love about the Chrysler Museum with a gift membership. Perfect for everyone on your list.

Learn about this innovative group of museum supporters. Meet the Masterpiece Society

Help ensure the long-term success of the Museum. Learn about planned giving

- Open today, 10 am to 5 pm.

- Parking & Directions

- Free Admission

Join Our Email List

Thomas cole’s voyage of life.

October 21, 2014 — January 18, 2015

Past Exhibition

The Hudson River School master Thomas Cole takes over the Chrysler Museum’s newly expanded American art galleries for a very special exhibition of his largest and finest works. Its centerpiece is Cole’s iconic series The Voyage of Life (1839–40), the pinnacle of his career and a landmark in Romantic landscape painting.

Spanning four monumental canvases, The Voyage of Life takes viewers on a journey through Childhood, Youth, Manhood, and Old Age , presenting each stage as progress along a grand but treacherous river.

These masterpieces from the collection of the Munson-Williams-Proctor Arts Institute in Utica, N.Y., are rarely loaned to other museums, and they embark on this historic tour together with many of the artist’s seldom-exhibited original drawings and preliminary studies. The Chrysler’s own Thomas Cole painting, The Angel Appearing to the Shepherds , the largest single canvas he ever created, joins this extraordinary tribute to one of the founding fathers of American art.

For more information, here’s a story from ArtFixDaily.com .

On view right now

James Baldwin: Celebrating a Legacy Exhibition Details

Early Days: Indigenous Art from the McMichael Canadian Art Collection Exhibition Details

The Voyage of Life - Youth

- Thomas Cole

* As an Amazon Associate, and partner with Google Adsense and Ezoic, I earn from qualifying purchases.

The Voyage of Life by Thomas Cole is a series of paintings that represents an allegory of the 4 stages of human life: old age, manhood, youth and childhood. The series traces an archetypal Everyman's religious journey.

The paintings were executed in 1842 and depict a voyage travelling in a boat on the river through the mid-nineteenth century American wilderness. In all the paintings , the voyager is seen riding his boat while a guardian angel accompanying him. The landscape plays an important part in conveying the story.

In childhood, the child is gliding from a cave into the rich, green landscape. Youth is also showing the rich, green landscape, but the view and the voyager's experience have widened. The youth is firmly grabbing the tiller as the angel waves and watches from the shore, which allows him to take control. A ghostly castle is hovering in the distance, which is a white, shimmering beacon representing the dreams and ambitions of man. The painting is located in the National Gallery of Art.

To the youth in the painting, the calm rivers lead right to the castle. But looking at the far right side of the painting, the viewer can glimpse the river as it's becoming choppy, rough and full of rocks. Cole stated that the scenery of the painting, including its clear stream, transparent atmosphere, its unbounded distance, its towering mountains and its lofty trees, shows the romantic beauty of youthful thoughts. This is when the brain elevates Common and Mean into the Magnificent before life experience teaches the Real state of things.

In manhood, the man relies on religious faith and prayer to sustain him through a threatening landscape and rough waters. The man finally grows old and the guardian angel is seen guiding him to heaven. The river flowing through the canvas reflects the twists and turns of life, while the time of day and season mirror each stage of life. From the childhood innocence to the glow of youthful overconfidence, and through the middle age's trials and tribulations to the triumphant salvation of the hero, The Voyage of Life by Thomas Cole seems intrinsically associated with the Christian doctrine of resurrection and death.

The artist's intrepid voyager may also be interpreted as the personification of America at an adolescent development stage. Cole might have been giving a dire warning to people caught up in the frenzied quest for Manifest Destiny: The unconstrained westward industrialization and expansion would have tragic outcomes for nature and man.

Cole was self-taught as a painter; he relied on studying the works of other artists and reading books. Cole derived the theme from the allegorical traditions, such as Pilgrim's Progress, John Bunyan's popular narrative. He influenced his artistic peers, particularly Frederic Edwin Church and Asher B. Durand, who studied with the artist between 1844 and 1846.

Article Author

Tom Gurney in an art history expert. He received a BSc (Hons) degree from Salford University, UK, and has also studied famous artists and art movements for over 20 years. Tom has also published a number of books related to art history and continues to contribute to a number of different art websites. You can read more on Tom Gurney here.

The Voyage Of Life: Childhood (1842) by Thomas Cole

Artwork Information

About the voyage of life: childhood.

Thomas Cole’s The Voyage of Life is a series of four paintings that represents the journey of human life. Childhood is the first painting in the series, completed by Cole in 1842. The painting portrays an idealistic world where a boat travels down a river amidst stunning landscapes that change to reflect each season and stage of life.

The painting features a guardian angel who accompanies the voyager on their journey through life, guiding them through various challenges when they need it most. This representation serves as an allegory for the four stages of man: childhood, youth, manhood, and old age. Childhood marks the beginning of this journey, as represented by the ever-flowing river, symbolizing time passing by.

Cole masterfully depicts an idyllic world typical snapshot representing childhood with vibrant colors portraying hope and innocence without any indication whatsoever on how challenging being young can be. The painting’s significant focus is on the boat travelling downriver, emphasising one’s lack of control over life events while relying heavily on external factors such as family or education(like having someone navigating your boat).

In conclusion, Thomas Cole’s Childhood creates a sentimental narrative to highlight how childhood is fleeting past quite fast and sets up future installments that further explore themes such as mortality or loss later in life for people who get to reach those stages.

Other Artwork from Thomas Cole

View from Mount Holyoke, Northampton, Massachusetts, after a Thunderstorm (The Oxbow) (1836) by Thomas Cole

The Course of Empire Desolation (1836) by Thomas Cole

The Voyage Of Life: Youth (1842) by Thomas Cole

The Clove, Catskills (c. 1827) by Thomas Cole

Schroon Mountain, Adirondacks (1838) by Thomas Cole

The Voyage of Life Old Age (1842) by Thomas Cole

More artwork from artchive.

Untitled (c.1988) by Kurt Cobain

Nature Morte À La Daurade (1920) by Henri Matisse

Reclining Nude on a Pink Couch (1919) by Henri Matisse

Lorette with Black Eyes (1917) by Henri Matisse

Champs De Blé À Cagnes (1918) by Henri Matisse

Two Deckchairs, Calvi (1972) by David Hockney

Ganesh-janani by Abanindranath Tagore

Sketch for Le Bonheur De Vivre (1906) by Henri Matisse

Skating in Holland (c.1890) by Johan Jongkind

Study for Luxe, Calme Et Volupté (1904) by Henri Matisse

Seated Nude (1906) by Henri Matisse

Self-portrait (1905) by Umberto Boccioni

We’re fighting to restore access to 500,000+ books in court this week. Join us!

Internet Archive Audio

- This Just In

- Grateful Dead

- Old Time Radio

- 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings

- Audio Books & Poetry

- Computers, Technology and Science

- Music, Arts & Culture

- News & Public Affairs

- Spirituality & Religion

- Radio News Archive

- Flickr Commons

- Occupy Wall Street Flickr

- NASA Images

- Solar System Collection

- Ames Research Center

- All Software

- Old School Emulation

- MS-DOS Games

- Historical Software

- Classic PC Games

- Software Library

- Kodi Archive and Support File

- Vintage Software

- CD-ROM Software

- CD-ROM Software Library

- Software Sites

- Tucows Software Library

- Shareware CD-ROMs

- Software Capsules Compilation

- CD-ROM Images

- ZX Spectrum

- DOOM Level CD

- Smithsonian Libraries

- FEDLINK (US)

- Lincoln Collection

- American Libraries

- Canadian Libraries

- Universal Library

- Project Gutenberg

- Children's Library

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Books by Language

- Additional Collections

- Prelinger Archives

- Democracy Now!

- Occupy Wall Street

- TV NSA Clip Library

- Animation & Cartoons

- Arts & Music

- Computers & Technology

- Cultural & Academic Films

- Ephemeral Films

- Sports Videos

- Videogame Videos

- Youth Media

Search the history of over 866 billion web pages on the Internet.

Mobile Apps

- Wayback Machine (iOS)

- Wayback Machine (Android)

Browser Extensions

Archive-it subscription.

- Explore the Collections

- Build Collections

Save Page Now

Capture a web page as it appears now for use as a trusted citation in the future.

Please enter a valid web address

- Donate Donate icon An illustration of a heart shape

The life and works of Thomas Cole

Bookreader item preview, share or embed this item, flag this item for.

- Graphic Violence

- Explicit Sexual Content

- Hate Speech

- Misinformation/Disinformation

- Marketing/Phishing/Advertising

- Misleading/Inaccurate/Missing Metadata

![[WorldCat (this item)] [WorldCat (this item)]](https://archive.org/images/worldcat-small.png)

plus-circle Add Review comment Reviews

2,620 Views

11 Favorites

DOWNLOAD OPTIONS

For users with print-disabilities

IN COLLECTIONS

Uploaded by TimB-foldout-op on April 8, 2011

SIMILAR ITEMS (based on metadata)

Thomas Cole

Get notified of book release

The angel and the voyager.

Why Are We Here and Where Are We Going?

Art—in all its vibrant, varied forms—wields a singular power to simultaneously reflect and reveal: reflecting what we know to be true from our own life journeys and revealing destinations of paths bypassed or yet untaken. The insight and creativity of an artist through this universal medium invites access to and assessment of that which appeals to and affects each individual mind and heart. Art can powerfully portray the universality of our time on earth: the natural life cycle of birth, growth, decay, and death. This process, once begun, marches forward at its own pace, indifferent to the qualms and delights of man. We are all in this process together, and we know it. Yet the passage of time, like the movement of clouds, is just slow enough that it is, at least most of the time, almost imperceptible.

Without fail, the older we get, the more compressed our earthbound sojourn tends to feel, forcing us to confront the brevity of our time on this planet. (This compression of time can occur sooner in our lives if we face an early loss of a loved one, major health problems, or other crises.) Whenever life’s fleetingness hits us, aspirations (wealth, success, approval) that once held so much appeal begin to lose their luster, and the chipping veneer alights in us a yearning for a more permanent, incorruptible source of hope.

Creators of art are often keenly aware of this fleetingness. “You just have to let go,” Martin Scorsese said when reflecting on death in an interview with The New York Times. “The point is to get rid of everything now. You’ve got to figure out who gets what or not. Often death is sudden. If you’re given the grace to continue working, you better figure out something that needs telling.” This seemingly brutal realism is echoed in the Psalms of the Bible: So teach us to number our days, That we may present to You a heart of wisdom. Psalm 90:12 Both Scorsese and the psalmist speak to the dilemma of mortality—the tension between knowing that our days are numbered and the uncertainty that follows as we determine how to spend our remaining time. In this book, we will use two series of paintings, The Voyage of Life and The Course of Empire by the influential nineteenth-century landscape painter Thomas Cole, as the primary lenses for evaluating different approaches to the dilemma of mortality. Also interwoven are surveys of cultural and artistic artifacts drawn from across disciplines and mediums. We endeavor not only to examine the inescapable finiteness of our time on earth, but to gain a richer perspective on the questions that naturally follow—questions fundamental to the human condition—namely: Why are we here? and Where are we going?

Thomas Cole: The Moralist and Autodidact

Thomas Cole was a British-American painter born in Bolton le Moors, Lancashire, England, in 1801, and raised in Steubenville, Ohio. Largely self-tutored, Cole represents the archetypal American figure of the autodidact. In his twenties, he moved to Philadelphia and then to Catskill, New York. The latter remained his home with the exception of a few years spent abroad until his death at age forty-seven. Although he is best known for his landscape art, he began his career in the early 1820s as a portrait painter.

Cole is widely regarded as the founder of the Hudson River School art movement, an informal group comprising landscape painters influenced by European Romanticism and American expansionism in their idyllic depictions of the American landscape. Cole’s significant impact is seen in the work of fellow painters Frederic Edwin Church, Albert Bierstadt, and Asher Brown Durand. Their artwork “aimed to depict nature in a peaceful, realistic, and also idealized way. Ruggedness existed alongside portrayals of ‘sublimity’ (that quality of unquantifiable greatness inspiring feelings of wonder, awe, and even terror). Such absorption in nature was in many ways a response to the increasing industrialization of the time.”

In his art, there is an immediate interplay between the pristine beauty of the breathtaking landscapes and the foreboding destruction brought on by civilization. Marked by a distinctive melancholy and religious undertones, Cole’s paintings are imbued with moralistic motifs that expose his own complex, evolving feelings about what he saw as the cyclical nature of life. industrialization of the time.”

As an artist, Cole saw his creative capacity as a directive to effect positive change. He wrote:

I have been dwelling on many subjects, and looking forward to the time when I can embody them on the canvas. They are subjects of a moral and religious nature. On such I think it the duty of the artist to employ his abilities: for his mission, if I may so term it, is a great and serious one. His work ought not to be a dead imitation of things without the power to impress a sentiment, or enforce a truth.

A deep reverence for nature—and, by extension, for its Creator—is immediately evident in Cole’s earliest paintings. In these first pieces, we see the rich depiction of nature that characterizes romanticism. A close look reveals strategic shading elements that explore underlying motifs of light and darkness—a technique that the artist heavily employs to explore religious themes in later paintings. Cole’s painting process began with field observation, during which he would make initial sketches and record detailed notes. The scene was then infused with Cole’s own “mind’s eye vision.” His detailed field notes on color, atmosphere, and geology, coupled with his imaginative interpretation, resulted in remarkable, idealized reproductions of nature scenes. In Landscape , Cole depicts pioneer efforts to tame the American wilderness. By contrast, Landscape with Indian offers what appears to be a more harmonious encounter between man and nature.

In another painting featuring Native Americans, Landscape with Figures: A Scene from “The Last of the Mohicans” , Cole captures the climax of James Fenimore Cooper’s acclaimed novel. Yet in depicting this epic literary scene, the imposing nature of Cole’s landscape causes its viewer to focus on the dominating, inevitable forces that eclipse the unfolding human drama.

In Expulsion. Moon and Firelight , Cole introduces allegory to his art. Eden (on the right side of the painting, representing the east) is joined to the fallen world by a bridge. To recreate this pivotal biblical scene in which Adam and Eve are expelled from the Garden of Eden (Genesis 3), Cole layered imaginative elements onto an image of a natural bridge that he observed in the White Mountains of New Hampshire in 1827. His subsequent paintings featuring the Garden of Eden draw a parallel between Eden and the pure, untainted American landscape.

Cole’s allegorical thread continues in The Subsiding of the Waters of the Deluge , which likens the American Revolution to the great flood of Genesis 7, both having birthed a new beginning after ridding the land of corruption. The Smithsonian American Art Museum identifies the symbolic elements in this painting:

A lone skull resting against the rocks suggests that the world has been washed clean of human folly. At the center of the painting, bathed in light, a dove flies toward land as the ark floats on the calm waters, ready to usher in a new and more enlightened era in America.

In The Angel Appearing to the Shepherds , Cole demonstrates his mastery of light and shadow. The Chrysler Museum of Art describes the artist’s striking portrayal of this key biblical scene (Luke 2:8–20):

The dramatic New Testament story unfolds in a sweeping nocturnal landscape struck by bursts of heavenly light. Appearing in golden light, an angel announces Christ’s birth to startled shepherds in the fields below; the light surrounding the angel serves as a symbol of spiritual awakening. The shepherds, for example, represent three successively higher states of spiritual response to the angel’s message, beginning with the stunned fear of the praying youth and culminating in the quiet understanding of the standing elder. Some scholars have noted that the middle shepherd bears a resemblance to Cole and may be an idealized self-portrait.

In 1833, Cole embarked on an epic five-part series chronicling the rise and fall of an imagined civilization. He was inspired by a trip to Europe, during which he saw for the first time the ruins of ancient civilization (something that could not be found in America at the time). Cole drew further inspiration from Bishop George Berkeley’s poem “Verses on the Prospect of Planting Arts and Learning in America,” which references the stages of civilization and the belief that America would be the next great empire. This prophecy rang true for Cole, moving him to create this anticipatory work.

In proposing this series to his patron, Luman Reed, Cole wrote:

A series of pictures might be painted that should illustrate the History of a natural scene, as well as be an Epitome of Man—showing the natural changes of Landscape & those effected by man in his progress from Barbarism to Civilization, to Luxury, the Vicious state or state of destruction and to the state of Ruin & Desolation.

The series opens to a view of raw, unaffected nature ( The Savage State ), from which peaceful farmland emerges ( The Arcadian or Pastoral State ). This scene is then supplanted by a flourishing, gilded civilization ( Consummation ), which succumbs to self-destruction by grisly warfare ( Destruction ). The series concludes with a panorama of ruins and nature’s gradual but certain reclamation ( Desolation ).

This series clearly reflects the artist’s anxiety about the dangers of urban expansion in America. Even as the scene dramatically transforms between paintings, a boulder balanced on a cliff in the distance remains unchanged, its constancy serving as a reminder of nature’s permanence, even while its precarious position points to the transience of man.

A contemporary of Cole, author James Fenimore Cooper praised The Course of Empire in 1849, stating, “Not only do I consider the Course of Empire the work of the highest genius this country has ever produced, but I esteem it one of the noblest works of art that has ever been wrought.”

While working on the iconic Course of Empire series, Cole produced a piece commonly known as The Oxbow . Created in response to British author Basil Hall’s criticism of a primitive, uncultured America, View from Mount Holyoke, Northampton, Massachusetts, after a Thunderstorm celebrates American landscape in all its glory. This painting presents a harmonious coexistence between unsettled and cultivated lands and a positive outlook for America’s future. Note that Cole himself appears as the painter perched upon the rocks. Cole has left another possible allusion to the Flood, having etched into the distant hills what appears to be the shape of Hebrew letters spelling out “Noah” and “Shaddai,” the latter being a reference to God “Almighty.”

Hudson River School artists were fueled by the poetry of transcendentalists Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, and Walt Whitman. Their writings, like the artists’ work, contrasted the insignificance of humanity with the infinity of nature. View on the Catskill—Early Autumn is one of many paintings in which Cole highlights the timeless flex of nature and cycles and seasons. However, later in his career, Cole’s paintings increasingly evinced a more robust theistic spirituality, a clear departure from the deistic, pantheistic, or individualistic approaches that characterized the transcendentalism of his time.

Several years after completing The Course of Empire paintings, Cole created another series centered on the themes of birth, growth, decay, and death. By this point in his career, Cole, now a well-known artist, was determined to use landscape painting to convey universal truths about the human condition; toward this end, he intentionally simplified the artistic style in this series (as compared to The Course of Empire ) to focus attention on the underlying moral and religious messages.

The Voyage of Life —our second focal series—follows the trajectory of one man’s journey on the river of life. Each of the four allegorical paintings depicts a season in the voyager’s life. In Childhood , he enters a fertile world as a babe, full of innocent wonder. In Youth , he charges ahead with confidence and ambition. In Manhood , he cries out for deliverance amidst the turbulent waters of middle age. And in Old Age , he sails peacefully toward his eternal home at the end of his days. Beyond addressing the state of adolescent America by highlighting the unforeseen, potentially destructive costs of Manifest Destiny (the nineteenth-century belief that the United States was destined to expand its reach across the continent), The Voyage of Life draws parallels to the Christian narrative of salvation and resurrection.

In each painting and stage of life, the voyager is guided by an angelic being whose presence he does not acknowledge until the final scene. This guardian angel faithfully accompanies the voyager through verdant hillsides and cragged cliffs, ultimately leading him to a vision of eternal life.

Cole painted two sets of The Voyage of Life , the first in 1839–1840 and the second in 1842, with only minor differences between the two. When the original series’ patron died in 1839, the attorney representing the patron’s family became increasingly adversarial in his dealings with Cole, ultimately stipulating that the first set of paintings would, upon leaving Cole’s possession, remain in a private collection, never to be seen by the public. This led Cole to paint a replica set while abroad in Rome. When he returned to America, he did not show the first series publicly, but only exhibited the second set. When he died, the first set was included in the March 1848 memorial exhibition held at the American Art Union. In June of that year, the Art Union voted to purchase the second set and distribute it by lottery. In this book we will focus on the second set of paintings.

After his two masterpiece series, Cole painted for six more years (until his death in early 1848), continuing to explore the theme of man’s relationship to and life within the context of nature, including paintings that seem to reveal a more peaceful, harmonious encounter.

A Pic-Nic Party , painted four years after the second Voyage of Life series, ostensibly presents a friendlier exchange between mankind and his surroundings. However, the tree stump in the foreground remains as a reminder of the cost of exchange between man and nature.

Home in the Woods also showcases Cole’s remarkable skill in simultaneously celebrating the fertile abundance of the untamed American landscape and exposing his concerns about the exploitation of natural resources. In his 1836 “Essay on American Scenery,” Cole lamented, “Yet I cannot but express my sorrow that the beauty of such [American] landscapes are quickly passing away—the ravages of the axe are daily increasing—the most noble scenes are made desolate, and oftentimes with a wantonness and barbarism scarcely credible in a civilized nation.”

When he died unexpectedly in February 1848, Cole left behind studies of an incomplete five-part series titled The Cross and the World . In this series, Cole limited the use of color to visually contrast the light of God against the darkness of sin. The first painting (study for Two Youths Enter Upon a Pilgrimage ) shows two young men embarking on divergent paths, one led by the promise of spiritual glory and the other lured by the seduction of earthly glory. A man stands between the two paths, gesturing toward the best option. He is an evangelist, ready to offer spiritual guidance to the youths, should they choose to listen.

The second and third paintings offer glimpses into each man’s journey midway. The path to spiritual glory is depicted as rugged and difficult for the pilgrim of the cross, while the path to earthly glory is well paved and easy for the pilgrim of the world. The final two paintings reveal the destinations of each traveler: The pilgrim of the cross has found spiritual peace (depicted in painting no. 4, The Pilgrim of the Cross at the End of His Journey ) while the pilgrim of the world has found his worldly pleasures wasted away by the passage of time (painting no. 5, The Pilgrim of the World at the End of His Journey ). Ultimately, the pilgrim of the cross discovered something profound, whereas the pilgrim of the world found squalor and emptiness.

Despite being unfinished, this set of paintings reveals much about Cole’s mindset in his last days. Through the series, he conveys truths about the paths we choose and what awaits us at the end of life. The pursuit of materialism and earthbound achievements ends in degradation, while the pursuit of spiritual riches and eternal glory ends with salvation and eternal life.

As this brief survey of his career shows, Cole’s romanticized compositions communicate the overwhelming beauty of the natural world while evoking questions about the divine. He subscribed to the idea, common to his time period, that art is a process of creation, not just a process of reproduction. In a sense, he and his contemporaries were imitating the creative power of the Almighty. Yet, Cole’s paintings also reveal a spirit of humility, signaling his understanding of mankind’s place in the grand scope of nature and eternity.

Memento Mori and the Cycles of Life

Equipped with a richer understanding of our focal paintings within the context of Cole’s whole career, we now turn to a brief study of some significant ways in which art illuminates and wrestles with the dilemma of mortality. Cole joins a long line of artists whose work addresses the cycles of life from birth through death. From the beginning of time, death has been considered the great unifier. Yet, for Christians, death is not the end.

Visual Memento Mori

Dance of Death, a fifteenth-century fresco, depicts men of different social rankings, lofty and laborers alike, being led to the grave, hand in hand. This work is emblematic of memento mori—reminders that we are all going to die natural deaths. Monk and Death is a French ivory pendant from the sixteenth or seventeenth century, revealing the underlying skull on one side of a near-dead monk’s face.

The straightforward display of Philippe de Champaigne’s Vanitas (1671) depicts life, death, and time. These works along with Thomas Smith’s Self-Portrait (1680) may strike us as morbid, but they were not unusual for their time. Smith, like his contemporaries, uses a skull to put into perspective other symbols representing key moments in his life journey.

The exterior panels of Rogier van der Weyden’s Braque Triptych (c. 1452), which show the skull of the patron, serve a similar function as the skull in Smith’s Self-Portrait. Triptychs were typically displayed opened, but the imagery of a skull resting on a broken brick (a possible representation of the patron’s profession) when the frame is closed serves as a visual reminder of what awaits each of us at the end of our lives in this world.

For another example of a work replete with memento mori, consider Hans Holbein the Younger’s painting The Ambassadors (1533). This extraordinary painting illustrates two young men who have achieved worldly success and are at the height of their prowess. Numerous symbols are present, but chief among them is the distorted skull in the foreground. An anamorphic painting, this piece reveals different imagery when viewed from different angles. The painting was probably intended to hang on the wall of a staircase so that, as one descended and looked down at the painting from the upper right, the skull would be clearly visible. The skull, coupled with the small crucifix in the top left corner, serves as a reminder of the viewer’s mortality and the need to turn to faith as the path to resurrection.

Another image of the universal awareness of human mortality is the Celtic cross, a religious symbol dating back to the early Middle Ages that offers a visual representation of the connectedness between earthly time and heavenly time. This symbol was often manifested in intricately decorated, freestanding stone structures called high crosses. One example, Muiredach’s High Cross, is pictured below.

Commissioned by King Muiredach (not much is known about him) and completed by an anonymous artist in the ninth or tenth century, Muiredach’s High Cross can be found at the monastic site of Monasterboice in County Louth, Ireland. Its design, like that of all Celtic crosses, emerged from the sun crosses of pre-Christian paganism.

History professor Dr. Glenn Sunshine describes how the design of the sun cross represented not only the sun but all of space and time:

The cross pointed to four cardinal directions, with east on the left, south on top, west on the right, and north on the bottom. The vertical line represented the “world tree” (Yggdrasil in Norse mythology), which tied the worlds together. The bottom was anchored in the underworld, the realm of the dead, and the top reached to heaven, the realm of the gods. The horizontal line represented this world, or “middle earth” between the lower and upper worlds. All that exists was thus symbolically represented in the diagram. When the sun cross was combined with the cross of Jesus Christ to form the Celtic cross, the circular design took on new symbolism, now representing God’s sovereignty over all of creation. Thus, the Celtic cross embodies both general revelation (knowledge of God through nature) and special revelation (knowledge of God through Scripture). At the same time, the Celtic cross continues to represent the cyclical nature of life, on a daily level (in which days replace days), on an annual level (in which years replace years), and in a life cycle (in which one generation follows another). We see this circularity reflected on multiple levels in our everyday lives. Each year, spring is the season of birth (and, not coincidentally, when we celebrate Christ’s resurrection); summer is the season of growth; fall is a season of decay; and winter is the season of death. As The Voyage of Life and The Course of Empire depict, a person’s life and a civilization’s rise and fall also follow the same trajectory of birth, growth, decay, and death. Cole’s work intimates that this circular motion also has a linearity—a telos (an end), a consummation. Life may be full of cycles, but the cycles are moving forward in an ultimate direction.

Memento Mori in Music

We have focused on visual art in our study of memento mori thus far, but other forms of creative expression have served similarly as conduits to explore the human condition of being embedded in this transient world. For example, music is a medium through which people have long wrestled with the dilemma of mortality. The following compositions, like the artwork we surveyed, call us to understand the essentials of life. We invite you to listen to and reflect on each of them.

- Gregorio Allegri, “Miserere mei, Deus” (1630s)

- Johann Sebastian Bach, “Come, Sweet Death” (1736)

- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, “Introitus,” from his Requiem (1791)

- Johannes Brahms, “Wie lieblich sind deine Wohnungen,” from his Requiem (1865–1868)

- Giuseppe Verdi, “Dies Irae,” from his Requiem (1874)

- Gabriel Fauré, “In Paradisum,” from his Requiem (1887–1890)

- Henryk Górecki, “Lento—Contabile Semplice,” from Symphony No. 3 (1976)

- Max Richter, “Dona Nobis Pacem 1,” from The Leftovers (2014)

- Karl Jenkins, “Lament for the Valley,” from Cantata Memoria—For the Children (2016)

One musical selection has a particularly powerful backstory. “Lament for the Valley” is a poignant piece in the album Cantata Memoria, composed by Karl Jenkins on the fiftieth anniversary of the Aberfan disaster. This devastating event killed 116 children and 29 adults when a colliery spoil tip collapsed upon the village below in South Wales. “Lament for the Valley” was written in two parts; the first describes the tragedy itself, and the second offers hope amidst lament. As such, Jenkins takes the listener on a journey from dark to light.

Memento Mori in Poetry

Three approaches to the dilemma of mortality.

Given the inevitability of death, how are we to spend our remaining days? Across history, people have taken one of three primary approaches to answering this question: resigning to futility; achieving “immortality” through art and achievement; or exchanging futility for hope in eternity. We can use poetry as a lens through which to better understand these approaches.

The third approach to the dilemma of mortality defines our life’s purpose not by the pain of our bounded past but by the joy of our unbounded future. In alignment with the biblical narrative of salvation, this approach teaches that neither hedonism nor achievement can secure immortality. Our time on earth is purposeful in that it prepares us for eternity. As Scripture teaches, we are sojourners “who desire a better country, that is, a heavenly one” (Hebrews 11:16). Those who believe in God live in faith and in anticipation of an assured future in heaven. John Donne and George Herbert convey as much in their poetry.

Vanitas Vanitatum

By john webster.

All the flowers of the spring

Meet to perfume our burying:

These have but their growing prime,

And man does flourish but his time.

Survey our progress from our birth;

We are set, we grow, we turn to earth.

Courts adieu, and all delights,

All bewitching appetites!

Sweetest breath, and clearest eye,

Like perfumes, go out and die;

And consequently this is done,

As shadows wait upon the sun.

Vain the ambition of kings,

Who seek by trophies and dead things

To leave a living name behind,

And weave but nets to catch the wind.

In this poetic excerpt of his play The Devil’s Law Case (1623), Webster exposes the futility of life, describing earthly pursuits of praise and conquest as vain and fleeting. Try as he might, even a king cannot catch the wind, for that which he seeks is unattainable.

In “To the Virgins, to Make Much of Time” (1648), Robert Herrick echoes Webster’s sentiment about the brevity of life but goes one step further to prescribe a response: since this world is all we have (so his reasoning goes), we should make the most of it by maximizing our pleasure and minimizing our pain.

To the Virgins, to Make Much of Time

By robert herrick.

Gather ye rose-buds while ye may,

Old Time is still a-flying;

And this same flower that smiles today,

Tomorrow will be dying.

The glorious lamp of heaven, the sun,

The higher he’s a-getting,

The sooner will his race be run,

And nearer he’s to setting.

That age is best which is the first,

When youth and blood are warmer;

But being spent, the worse, and worst

Times, still succeed the former.

Then be not coy, but use your time,

And while ye may, go marry;

For having lost but once your prime,

You may for ever tarry. Offering hedonism as a remedy to futility, Herrick makes the argument that we should spend our youth—the best stage of life, by his estimation—enjoying life to the fullest. Ultimately, the futility approach concludes that immortality cannot be achieved—that we are, in the final analysis, “food for the worms.” This approach fails to explain or satisfy the deep hunger innate in all people for an enduring meaning and purpose.

Other poets have rejected the futility approach, positing instead that immortality can be achieved— especially through art. This approach is described by William Butler Yeats in “Sailing to Byzantium” (1928).

Sailing to Byzantium

By william butler yeats.

That is no country for old men. The young In one another’s arms, birds in the trees, —Those dying generations—at their song, The salmon-falls, the mackerel-crowded seas, Fish, flesh, or fowl, commend all summer long Whatever is begotten, born, and dies. Caught in that sensual music all neglect Monuments of unageing intellect.

An aged man is but a paltry thing, A tattered coat upon a stick, unless Soul clap its hands and sing, and louder sing For every tatter in its mortal dress, Nor is there singing school but studying Monuments of its own magnificence; And therefore I have sailed the seas and come To the holy city of Byzantium.

O sages standing in God’s holy fire As in the gold mosaic of a wall, Come from the holy fire, perne in a gyre, And be the singing-masters of my soul. Consume my heart away; sick with desire And fastened to a dying animal It knows not what it is; and gather me Into the artifice of eternity.

Once out of nature I shall never take My bodily form from any natural thing, But such a form as Grecian goldsmiths make Of hammered gold and gold enamelling To keep a drowsy Emperor awake; Or set upon a golden bough to sing To lords and ladies of Byzantium Of what is past, or passing, or to come.

In this poem, Yeats laments the shabbiness of old age, and he dreams of being made into a golden bird, immortal and eternally beautiful. In referencing music in all four stanzas, he appears to already envision himself as such a bird, singing about what is passing, has passed, and is to come. As an artist, he supposes he has obtained some artifice of immortality if he can attain something through his work that is not related to his mortal body.

This second approach to mortality, which is essentially an achievement-based perspective, is ultimately unsatisfying as well. William Shakespeare wrote of the failure of a performance-driven approach to life in his play As You Like It. Artist Robert Smirke depicted Shakespeare’s “seven ages of man” in a series of paintings.

As You Like It, Act 2, Scene 7, Lines 140–164

By william shakespeare.

All the world’s a stage,

And all the men and women merely players:

They have their exits and their entrances; And one man in his time plays many parts, His acts being seven ages. At first, the infant,

Mewling and puking in the nurse’s arms. And then the whining school-boy, with his satchel

And shining morning face, creeping like snail

Unwillingly to school. And then the lover, Sighing like furnace, with a woeful ballad Made to his mistress’ eyebrow. Then a soldier,

Full of strange oaths, and bearded like the pard,

Jealous in honour, sudden and quick in quarrel,

Seeking the bubble reputation Even in the cannon’s mouth. And then the justice,

In fair round belly with good capon lined, With eyes severe and beard of formal cut, Full of wise saws and modern instances; And so he plays his part. The sixth age shifts

Into the lean and slipper’d pantaloon, With spectacles on nose and pouch on side; His youthful hose, well saved, a world too wide

For his shrunk shank; and his big manly voice,

Turning again toward childish treble, pipes And whistles in his sound. Last scene of all, That ends this strange eventful history, Is second childishness and mere oblivion, Sans teeth, sans eyes, sans taste, sans everything.

The problem with trying to achieve immortality through art is that such an endeavor inevitably leads to disappointment. Like the “bubble reputation” mentioned in the previously quoted, famous speech from As You Like It, earthly achievements are fleeting. Ultimately, we leave life as we came in: “sans teeth, sans eyes, sans taste, sans everything.” We arrived with nothing, and we will depart with nothing. We see this truth sink in at the end of The Tempest, when Prospero tells the audience: “Our revels now are ended. These our actors, as I foretold you, were all spirits and are melted into air, into thin air.”

Shakespeare speaks more personally to the ephemeral nature of life in Sonnet 30.

When to the sessions of sweet silent thought I summon up remembrance of things past, I sigh the lack of many a thing I sought, And with old woes new wail my dear time’s waste: Then can I drown an eye, unused to flow, For precious friends hid in death’s dateless night, And weep afresh love’s long-since-cancell’d woe, And moan the expense of many a vanisht sight: Then can I grieve at grievances foregone, And heavily from woe to woe tell o’er The sad account of fore-bemoaned moan, Which I new pay as if not paid before. But if the while I think on thee, dear friend, All losses are restored, and sorrows end. As the Bard reflects on his own life, he can’t help dwelling on his failures. He is filled with grief for all he has lost: friends, time, and opportunities. Life seems to have slipped through his fingers despite his best efforts.

Holy Sonnet X

By john donne.

Death, be not proud, though some have called thee

Mighty and dreadful, for thou art not so; For those whom thou think’st thou dost overthrow

Die not, poor Death, nor yet canst thou kill me. From rest and sleep, which but thy pictures be, Much pleasure; then from thee much more must flow, And soonest our best men with thee do go, Rest of their bones, and soul’s delivery. Thou’rt slave to fate, chance, kings, and desperate men, And dost with poison, war, and sickness dwell; And poppy or charms can make us sleep as well And better than thy stroke; why swell’st thou then? One short sleep past, we wake eternally, And death shall be no more: Death, thou shalt die.

Donne’s sonnet relates that death, while inevitable, is not the end. People are spiritual beings meant for greater heights than our finite time on earth allows. Herbert, in “Vanity (II),” a poem in his series The Temple (1633), speaks to this longing inside each of us, what C. S. Lewis called Sehnsucht, an aspiration for something more—something we cannot yet name.

Vanity (II)

By george herbert.

Poor silly soul, whose hope and head lies low;

Whose flat delights on earth do creep and grow:

To whom the stars shine not so fair, as eyes;

Nor solid work, as false embroideries; Hark and beware, lest what you now do measure

And write for sweet, prove a most sour displeasure.

O hear betimes, lest thy relenting May come too late! To purchase heaven for repenting, Is no hard rate. If souls be made of earthly mould, Let them love gold; If born on high, Let them unto their kindred fly: For they can never be at rest, Till they regain their ancient nest, Then silly soul take heed; for earthly joy Is but a bubble, and makes thee a boy.

Herbert warns against focusing so much on this world that we lose sight of the next, for (as he points out in lines 11–14) we are not made from or for this world. Since our souls do not, in fact, belong to the earth, we ought not invest in the temporal at the expense of the eternal. This realization leads to the question, “What can we do that will endure?”

This third approach to immortality, embodied in the poetry of both Donne and Herbert, draws on the teachings of the Bible (as indeed each poet did as well). This approach tells us that the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ resulted in the death of death, and the destiny of followers of Christ is directly tied to their relationship with their Savior. Because He lives, they will also live (John 14:19); because He rose from the dead, they too will rise from the dead:

So also is the resurrection of the dead. It is sown a perishable body, it is raised an imperishable body; it is sown in dishonor, it is raised in glory; it is sown in weakness, it is raised in power; it is sown a natural body, it is raised a spiritual body. If there is a natural body, there is also a spiritual body. . . . Behold, I tell you a mystery; we will not all sleep, but we will all be changed, in a moment, in the twinkling of an eye, at the last trumpet; for the trumpet will sound, and the dead will be raised imperishable, and we will be changed. For this perishable must put on the imperishable, and this mortal must put on immortality. But when this perishable will have put on the imperishable, and this mortal will have put on immortality, then will come about the saying that is written, “Death is swallowed up in victory. O death, where is your victory? O death, where is your sting?” The sting of death is sin, and the power of sin is the law; but thanks be to God, who gives us the victory through our Lord Jesus Christ.

1 Corinthians 15:42–44, 51–57

With this biblical teaching in mind, revisit Philippe de Champaigne’s Vanitas . Earlier, we reviewed three themes in this painting, represented by its three prominent symbolic objects: life, death, and time. Now, let us focus on the fourth and most important symbol: the shaped stone at the base, a representation of permanence and intentionality. According to Christianity, Jesus Christ is the stone which the builders rejected, and He has become the cornerstone of faith (Psalm 118:22). All is resting on Him; He is the One who created and holds space-time in His hand. Through Him, believers can claim victory over death and hope in eternity.

Cycles of Life

Many of those who sleep in the dust of the ground will awake, these to everlasting life.

Daniel 12:2a

Understanding our daily life cycle in this manner gives us perspective on the Bible’s principle of living each day without anxiety about the next day, free of the burden of a week’s—or year’s—worth of concerns.

So do not worry about tomorrow; for tomorrow will care for itself. Each day has enough trouble of its own.

Matthew 6:34

Followers of God are to live as though there are only two days in the calendar: today and that day—the day of Christ’s return. The goal is to always connect today with that day, thus living each day in anticipation of eternity.

Cole’s Faith, in Art

Though Cole’s art features obvious biblical themes, our knowledge of Cole’s personal faith is largely limited to the fact that he received baptism, confirmation, and communion in the Episcopal Church around 1842. However, we can infer from the allegorical elements embedded in his paintings a belief in the promise of an eternal home in heaven—and a belief in the God who makes this possible. As we study The Voyage of Life and The Course of Empire more closely, we will gain a richer understanding of the third approach to the dilemma of mortality.

Focal Paintings: The Voyage of Life and The Course of Empire

Painted over a ten-year span, the Voyage of Life and Course of Empire series share similar themes. Broadly speaking, both series record the passage of time and its effect on mankind and his natural surroundings. More specifically, we can observe parallels between the individual paintings by considering the works as corresponding pairings.

The first painting in The Voyage of Life series, Childhood, corresponds to the first two paintings of The Course of Empire series, The Savage State and The Arcadian or Pastoral State, in that all three depict nascency in a land that is largely untamed and untainted. Next, The Voyage of Life: Youth and The Course of Empire: The Consummation of Empire capture the lure of worldly success and ambition. The Voyage of Life: Manhood and The Course of Empire: Destruction show the collapse of earthly structures (literal and figurative) and the subsequent need for something more. Finally, The Voyage of Life: Old Age and The Course of Empire: Desolation close out their respective series with scenes of unexpected peace in the aftermath of destruction.

Childhood, The Savage State, and The Arcadian or Pastoral State

The voyage of life: childhood.

This magisterial series opens to a scene that contrasts the dark, mysterious unknown from whence we came with the rosy, blooming sunrise of new life. Although Cole was the first to take on the monumental task of creating coherent visual images on the allegorical subject of journeying through the river of life, notable literary pieces have done so as well, including John Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress.

To guide the viewer, Cole provided a written explanation for each painting in this series. About Childhood, he wrote:

A stream is seen issuing from a deep cavern, in the side of a craggy and precipitous mountain, whose summit is hidden in clouds. From out the cave glides a boat, whose golden prow and sides are sculptured into figures of the Hours: steered by an Angelic Form, and laden with buds and flowers…

The dark cavern is emblematic of our earthly origin, and the mysterious Past. The Boat, composed of Figures of the Hours, images the thought that we are borne on the hours down the Stream of Life. The Boat identifies the subject in each picture. The rosy light of the morning, the luxuriant flowers and plants, are emblems of the joyousness of early life. The close banks and the limited scope of the scene indicate the narrow experience of Childhood, and the nature of its pleasures and desires. The Egyptian Lotus in the foreground of the picture is symbolical of Human Life. Joyousness and wonder are the characteristic emotions of childhood.

Thomas Cole, 1840

Cole calls our attention to key symbolic elements in this painting. First, the fullness of the mountain’s summit is unseen, just as our entrance into this world is shrouded in mystery. Second, there is an hourglass at the front of the boat, representing the passage of time. Third, the child is oblivious to the presence of the angel who is guiding him at the tiller. Indeed, it isn’t until the final painting in the set, Old Age, that the voyager recognizes the guiding force in his life. Finally, this scene is abounding with natural beauty, evidenced in the blooms cascading from atop both boat and riverbank. A full and fertile world welcomes the child from a cave of chaos.

The Course of Empire: The Savage State

The Course of Empire begins with The Savage State, a vision of raw, untouched wilderness. Centered in the background is the mountain with the boulder balanced atop, visible in all five paintings. Looking closely, we observe a hunter on the bottom left; he has just shot an arrow at his prey, a deer leaping in the foreground. In the middle on the right, we see an encampment in a scene essentially borrowed from James Fenimore Cooper’s The Last of the Mohicans, of which Cole was a great admirer. On the water’s edge is a canoe, representing transportation and exploration. Dark storm clouds frame the painting, symbolizing the wildness of nature. Despite the signs of nascent civilization, nature dominates this stage.

The Course of Empire: The Arcadian or Pastoral State

The next painting in the series is The Arcadian or Pastoral State . Here, we see that some of the natural growth has been tamed and cultivated into farmland. Farmers and shepherds have replaced the hunter-gatherers—a move that signals permanent settlement. We see smoke rising from houses and more sophisticated boats in the water. There is an old man drawing figures in the dirt, symbolizing the beginning of mathematical discovery. A little boy is hunched over, drawing a stick figure of a man with a sword—the origins of art (Cole’s initials can be faintly seen below the boy on the stone bridge.)

The mountain is still visible in the background, although it seems more remote now. A building has been erected in the center of the painting, representing the beginning of monumental architecture and religion. At the bottom right, a tree stump serves as a harbinger of the violent dominance over nature by the artifice of man. Yet, for now, there remains a tenuous balance between the conqueror and the conquered, the latter of which seems harnessed but not quite overtaken (observe the shepherd boy tending to his sheep).

Where next?

Explore related content

The Voyage of Life: Manhood

James smillie engraved after thomas cole 1853/1856, hudson river museum yonkers, ny, united states.

Thomas Cole is considered the founder of the Hudson River School, a nineteenth-century American art movement. He was fervently religious and devoted to painting the American countryside as well as allegorical subjects that depicted fantastical scenery that illustrated stories with moral elements. This print is based on one of four paintings in Cole’s Voyage of Life series.

Despite the conceptual nature of the subject and its imaginary locale, Wallace Bruce, author of the Hudson by Daylight (1872) and A Panorama of the Hudson (1888), saw these scenes as based on Catskills and Hudson River scenery: “Truly the Catskills were a fitting place for the artist Cole to gather inspiration to complete that beautiful series of paintings, The Voyage of Life.”

- Title: The Voyage of Life: Manhood

- Creator: James Smillie engraved after Thomas Cole

- Date Created: 1853/1856

- Provenance: Gift of Mrs. A. J. S. Machin, 1946 (46.176c)

- Type: Print

- Medium: engraving

Get the app

Explore museums and play with Art Transfer, Pocket Galleries, Art Selfie, and more

- Arts & Photography

- Individual Artists

Enjoy fast, free delivery, exclusive deals, and award-winning movies & TV shows with Prime Try Prime and start saving today with fast, free delivery

Amazon Prime includes:

Fast, FREE Delivery is available to Prime members. To join, select "Try Amazon Prime and start saving today with Fast, FREE Delivery" below the Add to Cart button.

- Cardmembers earn 5% Back at Amazon.com with a Prime Credit Card.

- Unlimited Free Two-Day Delivery

- Streaming of thousands of movies and TV shows with limited ads on Prime Video.

- A Kindle book to borrow for free each month - with no due dates

- Listen to over 2 million songs and hundreds of playlists

- Unlimited photo storage with anywhere access

Important: Your credit card will NOT be charged when you start your free trial or if you cancel during the trial period. If you're happy with Amazon Prime, do nothing. At the end of the free trial, your membership will automatically upgrade to a monthly membership.

Buy new: .savingPriceOverride { color:#CC0C39!important; font-weight: 300!important; } .reinventMobileHeaderPrice { font-weight: 400; } #apex_offerDisplay_mobile_feature_div .reinventPriceSavingsPercentageMargin, #apex_offerDisplay_mobile_feature_div .reinventPricePriceToPayMargin { margin-right: 4px; } $30.00 $ 30 . 00 FREE delivery September 9 - 10 on orders shipped by Amazon over $35 Ships from: Amazon.com Sold by: Amazon.com

Return this item for free.

We offer easy, convenient returns with at least one free return option: no shipping charges. All returns must comply with our returns policy.

- Go to your orders and start the return

- Select your preferred free shipping option

- Drop off and leave!

Save with Used - Acceptable .savingPriceOverride { color:#CC0C39!important; font-weight: 300!important; } .reinventMobileHeaderPrice { font-weight: 400; } #apex_offerDisplay_mobile_feature_div .reinventPriceSavingsPercentageMargin, #apex_offerDisplay_mobile_feature_div .reinventPricePriceToPayMargin { margin-right: 4px; } $26.02 $ 26 . 02 $3.98 delivery August 31 - September 3 Ships from: glenthebookseller Sold by: glenthebookseller

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

Follow the author

The Voyage of Life: The Sacred Vision of Thomas Cole Hardcover – March 11, 2023

Purchase options and add-ons.

- Print length 116 pages

- Language English

- Publisher Angelico Press

- Publication date March 11, 2023

- Dimensions 7.5 x 0.44 x 9.25 inches

- ISBN-10 1621389154

- ISBN-13 978-1621389156

- See all details

Customers who bought this item also bought

Editorial Reviews

From the back cover, about the author, product details.

- Publisher : Angelico Press (March 11, 2023)

- Language : English

- Hardcover : 116 pages

- ISBN-10 : 1621389154

- ISBN-13 : 978-1621389156

- Item Weight : 1.08 pounds

- Dimensions : 7.5 x 0.44 x 9.25 inches

- #1,001 in Religious Arts & Photography

- #2,889 in Individual Artist Monographs

- #7,876 in Arts & Photography Criticism

About the author

Addison hodges hart.

ADDISON HODGES HART is the author of eleven books (with two to be published in 2023) on various subjects, including biblical commentary, religious studies, interfaith contemplative traditions, and fiction. He is also the author of the Substack page, "The Pragmatic Mystic." After two decades as a university chaplain and vicar, he now resides in Norway with his wife.

Customer reviews

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 5 star 38% 23% 0% 0% 39% 38%

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 4 star 38% 23% 0% 0% 39% 23%

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 3 star 38% 23% 0% 0% 39% 0%

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 2 star 38% 23% 0% 0% 39% 0%

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 1 star 38% 23% 0% 0% 39% 39%

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

- Sort reviews by Top reviews Most recent Top reviews

Top reviews from the United States

There was a problem filtering reviews right now. please try again later..

Top reviews from other countries

- Amazon Newsletter

- About Amazon

- Accessibility

- Sustainability

- Press Center

- Investor Relations

- Amazon Devices

- Amazon Science

- Sell on Amazon

- Sell apps on Amazon

- Supply to Amazon

- Protect & Build Your Brand

- Become an Affiliate

- Become a Delivery Driver

- Start a Package Delivery Business

- Advertise Your Products

- Self-Publish with Us

- Become an Amazon Hub Partner

- › See More Ways to Make Money

- Amazon Visa

- Amazon Store Card

- Amazon Secured Card

- Amazon Business Card

- Shop with Points

- Credit Card Marketplace

- Reload Your Balance

- Amazon Currency Converter

- Your Account

- Your Orders

- Shipping Rates & Policies

- Amazon Prime

- Returns & Replacements

- Manage Your Content and Devices

- Recalls and Product Safety Alerts

- Registry & Gift List

- Conditions of Use

- Privacy Notice

- Consumer Health Data Privacy Disclosure

- Your Ads Privacy Choices

A startup wants travelers to live on a cruise ship for 3 years. See what the $181,790 global voyage promises.

- GlobeCruises says its three-year world cruise will sail in April 2025, starting at $181,790 per person.

- The voyage would visit 413 ports in 171 countries, although the startup has yet to acquire a ship.

- Its CEO and COO worked for Life at Sea , a three-year cruise project that recently filed for bankruptcy.

A startup is inviting travelers to live on a cruise ship for three years as it sails around the world.

GlobeCruises says its 1,095-day voyage will depart Barcelona on April 12, 2025. From there, it would visit 413 ports in 171 countries before concluding in Southampton, England, on April 13, 2028.

Along the way, travelers could experience the night markets of Taiwan, the beaches of Brazil, the wildlife of Tanzania, and the landmarks of Spain.

The startup's COO, Robert Dixon, told Business Insider that the voyage was designed to chase warm weather. But according to its itinerary , destinations will stretch as far south as chilly Antarctica and as far north as Longyearbyen, Norway.

Dixon said the cruise would also dock overnight at 355 of the 413 ports — in some cases for as long as seven nights, like in Singapore — giving guests more time to explore the destinations.

Inside cabins start at about $181,790 per person, while the more luxurious suites cost $624,150 per person. The cheapest option costs about $166 per person and day.

Demand has been growing in recent years for extended cruises, but their duration is typically several months, not years. Oceania's 2024 six-month world cruise sold out within 30 minutes of reservations opening in 2022, the premium cruise line said at the time. Cruise lines like Regent Seven Seas and Silversea operate annual around-the-world sailings, most of which are capped at four to six months.

GlobeCruises is promising an activity-filled ship

GlobeCruises says its vessel will have amenities like a gym, a movie theater, a nightclub, and rentable offices. To pass the time, guests could take a dip in the pool, crack open a new book in the library, or relax in the spa.

Kendra Holmes, GlobeCruises' CEO, said she envisions at least two pools and restaurants and "as many bars and lounges" as possible, but no casino — which is a popular feature of some cruises.

The company also promises a scuba diving certification program and homeschooling opportunities for its youngest guests. The ship would host entertainers and chefs local to the port stops, as well.

Related stories

The concept is similar to Life at Sea

GlobeCruises' plans are similar to those of now-defunct Life at Sea Cruises . The latter canceled its planned three-year voyage in November 2023, two weeks before its departure, after failing to secure enough funding to purchase a ship.

Dixon and Holmes previously worked with Life at Sea. Holmes served as CEO of its parent company, Miray Cruises , until her departure about a week before the company canceled its global voyage.

Dixon told BI that he helped develop the concept for Life at Sea and later brought it to Miray. He said he left the team in late October 2023, a couple of weeks after Miray said it couldn't acquire a vessel.

In January, 78 would-be Life at Sea cruisers sent a letter to Markenzy Lapointe, the US attorney for the Southern District of Florida, asking him to investigate Miray Cruises for criminal fraud. The letter accused the company of using about $16 million of its customers' funds to pay for a ship it didn't purchase.

In July, Life at Sea Cruises filed for bankruptcy.

The company's demise is "in the past," Holmes told BI.

"I can't dwell, but it's terrible it happened," Holmes said. "We all put our hearts and souls into it, and at the end of the day, it fell apart. I hate to say 'shit happens,' but shit happens."

To avoid another failed launch, Dixon said GlobeCruises has partnered with ship management firm Anglo-Eastern. The Hong Kong-based company has "expressed their confidence in the viability of our project." (Anglo-Eastern did not immediately respond to a request for comment from BI.)

But there is a caveat: GlobeCruises still needs a ship.

GlobeCruises doesn't have a ship — yet

Holmes said GlobeCruises would use investor money — not guest deposits — to pay for its future vessel.

Dixon told BI that he has already secured funding to "commit to" a ship and has narrowed the choice to three options that are currently in operation and would ideally accommodate 1,200 to 1,500 passengers

He said he aims to announce his final pick in early September and take ownership of the vessel in February 2025, two months before the start of the voyage.

In the meantime, guests can reserve the world cruise by signing a commitment contract. A 20% deposit would be due 14 days after GlobeCruises announces their ship of choice, and held in escrow until the sailing begins, Holmes said.

"At the end of the day, if we aren't able to get the investor support we need and we aren't able to acquire a ship, we're not going to sail," Holmes said. "That's something we're focusing on this time to make people feel more comfortable."

Travelers who don't want to pay at least $181,790 can book cheaper and shorter segments of the cruise. Holmes also suggested guests get a travel loan instead of selling their homes and cars. Some Life at Sea buyers had sold many of their belongings ahead of the ultimately canceled voyage.

Rival cruise Villa Vie could soon set sail

Holmes said several would-be Life at Sea guests have signed commitment contracts for her new project. (She declined to share the exact number.)

Villa Vie Residences , a never-ending cruise startup, has also attracted some travelers who've been burned by the recent demise or delay of other residential cruise concepts, such as Storylines and Victoria Cruises Line .

Villa Vie was founded by another Life at Sea alum, Mikael Petterson. But unlike the newer startup, Petterson's company already has a ship that could embark "any day now," he told BI in an email on Monday.

Despite the two companies' shared history, Dixon said there's no bad blood. He said he wants Villa Vie to succeed.

"I want people to go on Petterson's adventure," Dixon told BI. "It's going to be a door opener for the whole industry. It makes it easier for us because then there's a bit of confidence in this whole concept."

Are you sailing on a residential cruise ship like Villa Vie or have a tip? Contact the reporter at [email protected] or on X @brittanymchang .

Watch: Cruise ship captain breaks down 8 cruise ship disasters in movies and TV

- Main content

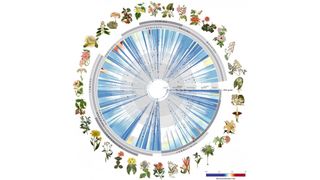

What is the 'tree of life'?

The tree of life maps out the relationships between all living things, and it's in constant flux.

All species on Earth, both living and extinct, are related. We know this because of a biological tool called the tree of life. This "tree" takes the form of a diagram that maps the relationships between plants, animals and other organisms. Its "trunk" successively forks into millions of ever-more intricate "branches," each of which represents a new strand of life.

The origins of this biological metaphor are difficult to trace, because scientists throughout history have tried to visually depict the relationships among organisms in tree-style diagrams. But most scientists credit the modern inception of the tree to Charles Darwin.

"'The really big thing with Darwin is that he has a mechanism by which the different branches actually occur," said Ian Barnes , a molecular evolutionary biologist at the Natural History Museum in the United Kingdom. That mechanism, of course, is evolution , Barnes told Live Science.

Related: Charles Darwin's stolen 'tree of life' notebooks returned after 20 years

According to Darwin, all life on earth originated from a single ancestor: in future decades, research would go on to show that there was likely a " last universal common ancestor " (LUCA) — a cell that existed about 4.2 billion years ago, from which all life on Earth evolved. Today, LUCA represents the thick base of the tree, and from this foundation, the tree parts into three sturdy branches. "Your first starting groups would be Bacteria, Eukarya and Archaea," Barnes said — the three primary domains of life.

If we trace from the finer twigs back to the thicker branches of the tree, it shows us how all life on Earth is connected and how close or distant those relationships are, Barnes explained. The fewer the branches between two species, the more closely they are related.

However, "the tree is not an immutable, static thing," Barnes added. Historically, scientists based the tree of life on painstaking observations of the physical differences between living things because it was the only tool they had to determine how closely related organisms were. But now, we have DNA analysis, which can reveal how much genetic material two organisms have in common and, therefore, in many cases it can show more conclusively how close their relationship is.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Each branch on the tree signifies the splitting of a common ancestor into two or more descendants — a process powered by natural selection. Take Eukarya, for example. This huge branch includes all multicellular life. Over the course of millions of years, it splits into distinct evolutionary lineages known as clades . A clade encompasses an ancestor and all descendants that spring from it.

Eukarya includes three familiar clades: plants, fungi and animals. Following the animal clade, which is defined as a "kingdom," there is a point in the tree where two new clades form from the divergence of animals into invertebrates (those without a spinal column) and vertebrates (those with a spinal column). The group Vertebrata then branches into several clades of its own, including mammals. From this class, through successive branching over millions of years, our species, Homo sapiens , eventually emerged.

— Genomes of 51 animal species mapped in record time, creating 'evolutionary time machine'

— Human origins tied to ancient jawless blood-sucking fish

— Here's what the last common ancestor of apes and humans looked like

In fact, DNA analysis has shown that the foundational relationships that were historically represented on the tree are surprisingly accurate. But our modern tools have also redrawn connections on some branches. "Even now if we generate more DNA sequence data, or we analyze it in a different way, we are changing the relationships on the tree," Barnes said.

Despite these continuous changes, the tree of life remains a highly useful tool, he added. By revealing relationships among species, the tree of life has helped scientists identify new candidates for pharmaceutical treatments, for instance. Looking at the tree can also reveal how life has ebbed and flowed over time, as well as allow us to compare historical extinction rates with those today and understand their drivers, Barnes said.

"It's not just a cartoon of the relationships between organisms, which would be pretty useful in itself," he added. “But particularly once we can put a timescale onto things, it actually becomes an analytical tool."

Emma Bryce is a London-based freelance journalist who writes primarily about the environment, conservation and climate change. She has written for The Guardian, Wired Magazine, TED Ed, Anthropocene, China Dialogue, and Yale e360 among others, and has masters degree in science, health, and environmental reporting from New York University. Emma has been awarded reporting grants from the European Journalism Centre, and in 2016 received an International Reporting Project fellowship to attend the COP22 climate conference in Morocco.

Continental collision 2.1 billion years ago may have sparked '1st attempt' at complex life on Earth

Human origins tied to ancient jawless blood-sucking fish

Meet LUCA, the 4.2 billion-year-old cell that's the ancestor of all life on Earth today

Most Popular

- 2 Viking Age stone figurine unearthed in Iceland — but no one can agree on which animal it is

- 3 'Once-in-a-lifetime' photo: Perseid meteors, northern lights and rare glowing arc shine over 11th-century castle

- 4 'A single magma ocean' once covered the moon, data from India's Chandrayaan-3 mission suggests

- 5 Chlamydia may hide in the gut and cause repeated infections

COMMENTS

A series of four paintings by Thomas Cole depicting the stages of human life as a journey on a river through the American wilderness. Learn about the allegory, the background, the versions, and the details of each painting.